One year ago, the World Health Organization declared the spread of COVID-19 a worldwide pandemic. Reacting to the virus, schools at every level were sent scrambling. Institutions across the world switched to virtual learning, with teachers, students, and local leaders quickly adapting to an entirely new way of life. A year later, schools are beginning to reopen, the $1.9 trillion stimulus bill has been passed, and a sense of normalcy seems to finally be in view; in President Joe Biden’s speech last night, he spoke of “finding light in the darkness.” But it’s safe to say that COVID-19 will end up changing education forever, casting a critical light on everything from equity issues to ed tech to school financing.

Below, Brookings experts examine how the pandemic upended the education landscape in the past year, what it’s taught us about schooling, and where we go from here.

Daphna Bassok — Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: COVID-19 highlighted the essential role of child care for children, families, and the economy, and our serious underinvestment in the care sector.

Daphna Bassok — Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: COVID-19 highlighted the essential role of child care for children, families, and the economy, and our serious underinvestment in the care sector.

In the United States, we tend to focus on the educating roles of public schools, largely ignoring the ways in which schools provide free and essential care for children while their parents work. When COVID-19 shuttered in-person schooling, it eliminated this subsidized child care for many families. It created intense stress for working parents, especially for mothers who left the workforce at a high rate.

The pandemic also highlighted the arbitrary distinction we make between the care and education of elementary school children and children aged 0 to 5. Despite parents having the same need for care, and children learning more in those earliest years than at any other point, public investments in early care and education are woefully insufficient. The child-care sector was hit so incredibly hard by COVID-19. The recent passage of the American Rescue Plan is a meaningful but long-overdue investment, but much more than a one-time infusion of funds is needed. Hopefully, the pandemic represents a turning point in how we invest in the care and education of young children—and, in turn, in families and society.

Lauren Bauer — Fellow in Economics Studies and in The Hamilton Project: Just over a year ago, before the U.S. locked down, Diane Schanzenbach and I wrote a piece on how to prevent the foreseeable food-insecurity crisis. We argued that, if schools were closed, there had to be an aggressive solution to make up for the loss of the School Breakfast Program and National School Lunch Program. Pandemic EBT is a program that Congress authorized to replace missed prepared school meals with a grocery store voucher. We evaluated the effect of Pandemic EBT on measures of food hardship as it rolled out over the country last summer, finding that it reduced the share of households reporting that their children did not have enough to eat by 30%.

Lauren Bauer — Fellow in Economics Studies and in The Hamilton Project: Just over a year ago, before the U.S. locked down, Diane Schanzenbach and I wrote a piece on how to prevent the foreseeable food-insecurity crisis. We argued that, if schools were closed, there had to be an aggressive solution to make up for the loss of the School Breakfast Program and National School Lunch Program. Pandemic EBT is a program that Congress authorized to replace missed prepared school meals with a grocery store voucher. We evaluated the effect of Pandemic EBT on measures of food hardship as it rolled out over the country last summer, finding that it reduced the share of households reporting that their children did not have enough to eat by 30%.

Congressional reauthorization of Pandemic EBT for this school year, its extension in the American Rescue Plan (including for summer months), and its place as a central plank in the Biden administration’s anti-hunger agenda is well-warranted and evidence based. But much more needs to be done to ramp up the program–even today, six months after its reauthorization, about half of states do not have a USDA-approved implementation plan.

Stephanie Cellini — Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: The pandemic has affected nearly every facet of higher education, but what is most striking to me is the dramatic decline in community college enrollment. Typically, we see enrollment in community colleges increase during recessions as unemployed individuals seek new skills and first-time students look to gain a credential before embarking on a career path. In this recession, the pattern is reversed: Enrollment in community colleges has dipped by about 10% since last year. Declines are particularly sharp among first-time students and students of color, raising critical concerns about increasing inequality in the coming years.

Stephanie Cellini — Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: The pandemic has affected nearly every facet of higher education, but what is most striking to me is the dramatic decline in community college enrollment. Typically, we see enrollment in community colleges increase during recessions as unemployed individuals seek new skills and first-time students look to gain a credential before embarking on a career path. In this recession, the pattern is reversed: Enrollment in community colleges has dipped by about 10% since last year. Declines are particularly sharp among first-time students and students of color, raising critical concerns about increasing inequality in the coming years.

In contrast, enrollment is up in for-profit and online colleges. The research repeatedly finds weaker student outcomes for these types of institutions relative to community colleges, and many students who enroll in them will be left with more debt than they can reasonably repay. The pandemic and recession have created significant challenges for students, affecting college choices and enrollment decisions in the near future. Ultimately, these short-term choices can have long-term consequences for lifetime earnings and debt that could impact this generation of COVID-19-era college students for years to come.

Helen Shwe Hadani — Fellow in the Center for Universal Education and in the Metropolitan Policy Program: Academic learning losses in reading and math are a growing concern across the U.S. and globally, especially for children living in low-resourced communities that have been disproportionally affected by the abrupt shift to remote schooling. However, many are equally concerned about the harder-to-predict developmental effects of ongoing social deprivation, both in and out of school, for children. A core part of children’s social experience—interacting with other kids in school and on playdates—has been stripped away and disappointingly replaced with virtual get-togethers and pandemic school.

Helen Shwe Hadani — Fellow in the Center for Universal Education and in the Metropolitan Policy Program: Academic learning losses in reading and math are a growing concern across the U.S. and globally, especially for children living in low-resourced communities that have been disproportionally affected by the abrupt shift to remote schooling. However, many are equally concerned about the harder-to-predict developmental effects of ongoing social deprivation, both in and out of school, for children. A core part of children’s social experience—interacting with other kids in school and on playdates—has been stripped away and disappointingly replaced with virtual get-togethers and pandemic school.

Many U.S. educationalists are drawing on the “build back better” refrain and calling for the current crisis to be leveraged as a unique opportunity for educators, parents, and policymakers to fully reimagine education systems that are designed for the 21st rather than the 20th century, as we highlight in a recent Brookings report on education reform. An overwhelming body of evidence points to play as the best way to equip children with a broad set of flexible competencies and support their socioemotional development. A recent article in The Atlantic shared parent anecdotes of children playing games like “CoronaBall” and “Social-distance” tag, proving that play permeates children’s lives—even in a pandemic.

Michael Hansen — Director of and Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: Standardized testing is one of many school rituals abandoned last spring as the unfolding pandemic swept the globe. Last month, the Department of Education announced it would not give states blanket waivers of standardized tests this spring, though offered flexibility in meeting testing mandates this year. With many school leaders balking at the announcement, however, uncertainty remains about what tests will look like. My view: Let’s use this opportunity to revisit how we test students.

Michael Hansen — Director of and Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: Standardized testing is one of many school rituals abandoned last spring as the unfolding pandemic swept the globe. Last month, the Department of Education announced it would not give states blanket waivers of standardized tests this spring, though offered flexibility in meeting testing mandates this year. With many school leaders balking at the announcement, however, uncertainty remains about what tests will look like. My view: Let’s use this opportunity to revisit how we test students.

Tests play a critical role in our school system. Policymakers and the public rely on results to measure school performance and reveal whether all students are equally served. But testing has also attracted an inordinate share of criticism, alleging that test pressures undermine teacher autonomy and stress students. Much of this criticism will wither away with different formats. The current form of standardized testing—annual, paper-based, multiple-choice tests administered over the course of a week of school—is outdated. With widespread student access to computers (now possible due to the pandemic), states can test students more frequently, but in smaller time blocks that render the experience nearly invisible. Computer adaptive testing can match paper’s reliability and provides a shorter feedback loop to boot. No better time than the present to make this overdue change.

Douglas N. Harris — Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: The COVID-19 school closures have fundamentally changed, and largely undermined, schools for more than a year. This is just the beginning. First, it will take some years for schools to find ways to get current students back on track—academically, physically, mentally, and otherwise. Second, while students, parents, and teachers have been pushed out of their comfort zones for a year, and will seek a return to normalcy, they will also realize that they liked some COVID-19 schooling changes and will push, from the bottom-up, to maintain them. My high schooler, for one, would like a later start time and about half as much time at school.

Douglas N. Harris — Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: The COVID-19 school closures have fundamentally changed, and largely undermined, schools for more than a year. This is just the beginning. First, it will take some years for schools to find ways to get current students back on track—academically, physically, mentally, and otherwise. Second, while students, parents, and teachers have been pushed out of their comfort zones for a year, and will seek a return to normalcy, they will also realize that they liked some COVID-19 schooling changes and will push, from the bottom-up, to maintain them. My high schooler, for one, would like a later start time and about half as much time at school.

A third push for change will come from the outside in. COVID-19 has reminded us not only of how integral schools are, but how intertwined they are with the rest of society. This means that upcoming schooling changes will also be driven by the effects of COVID-19 on the world around us. In particular, parents will be working more from home, using the same online tools that students can use to learn remotely. This doesn’t mean a mass push for homeschooling, but it probably does mean that hybrid learning is here to stay.

Brad Olsen — Senior Fellow in the Center for Universal Education: The COVID-19 pandemic has caused untold devastation across the world, yet it’s also revealed some interesting truths about education. It’s taught us that teachers, learners, and caregivers are incredibly resilient, but not indefatigable. It’s taught us that technology can be wonderful, but it will never replace the value of people in safe but rigorous learning spaces talking, playing, and working together. It’s taught us that a 20th-century model of schooling must be updated to prioritize the human aspects of education—not the mechanical ones—and push education to be simultaneously individualized and of common purpose. It’s taught us that we ignore opportunity inequities at our own cost and at the expense of the most vulnerable. It’s taught us that teachers should not be taken for granted. It’s taught us that not everything in the curriculum matters and not everything that matters fits into the curriculum. And it’s taught us that schools must stock up on hand soap!

Brad Olsen — Senior Fellow in the Center for Universal Education: The COVID-19 pandemic has caused untold devastation across the world, yet it’s also revealed some interesting truths about education. It’s taught us that teachers, learners, and caregivers are incredibly resilient, but not indefatigable. It’s taught us that technology can be wonderful, but it will never replace the value of people in safe but rigorous learning spaces talking, playing, and working together. It’s taught us that a 20th-century model of schooling must be updated to prioritize the human aspects of education—not the mechanical ones—and push education to be simultaneously individualized and of common purpose. It’s taught us that we ignore opportunity inequities at our own cost and at the expense of the most vulnerable. It’s taught us that teachers should not be taken for granted. It’s taught us that not everything in the curriculum matters and not everything that matters fits into the curriculum. And it’s taught us that schools must stock up on hand soap!

I am hoping we will use this forced rupture in the fabric of schooling to jettison ineffective aspects of education, more fully embrace what we know works, and be bold enough to look for new solutions to the educational problems COVID-19 has illuminated.

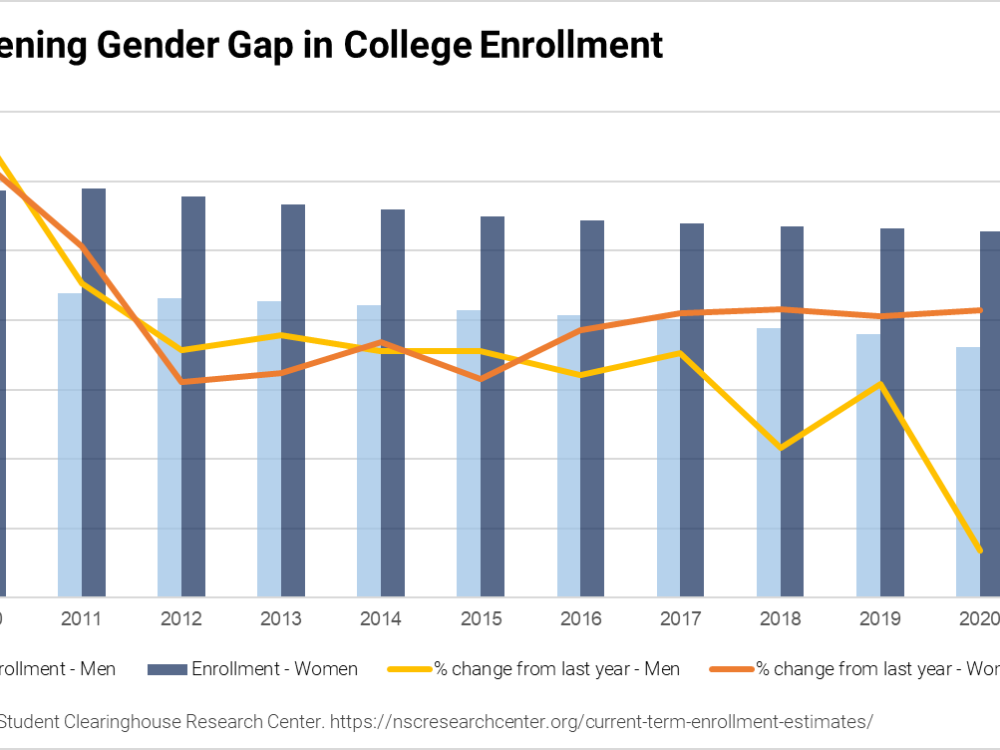

Richard V. Reeves — Senior Fellow in Economics Studies: For obvious reasons, the pandemic has hit college enrollment numbers hard. The biggest decreases have been at the undergraduate level, and above all for community colleges. Protecting the finances of these institutions is obviously a key policy concern. Of course, the longer-term effects for social mobility of a disrupted transition to postsecondary education are the deeper concern, along with the consequences for racial and economic equity. But an overlooked dimension of the challenge is the stark gender gap. College enrollment for male students in fall 2020 dropped by 5.1%, according to National Student Clearinghouse figures, several times more than the fall for female students (0.7%). The drop in enrollment in previous years has also been much bigger for men than women, and, as the chart below shows, it comes against the backdrop of lower overall rates of enrollment in the first place.

Richard V. Reeves — Senior Fellow in Economics Studies: For obvious reasons, the pandemic has hit college enrollment numbers hard. The biggest decreases have been at the undergraduate level, and above all for community colleges. Protecting the finances of these institutions is obviously a key policy concern. Of course, the longer-term effects for social mobility of a disrupted transition to postsecondary education are the deeper concern, along with the consequences for racial and economic equity. But an overlooked dimension of the challenge is the stark gender gap. College enrollment for male students in fall 2020 dropped by 5.1%, according to National Student Clearinghouse figures, several times more than the fall for female students (0.7%). The drop in enrollment in previous years has also been much bigger for men than women, and, as the chart below shows, it comes against the backdrop of lower overall rates of enrollment in the first place.

There is already a large gender gap in education in the U.S., including in high school graduation rates, and increasingly in college-going and college completion. While the pandemic appears to be hurting women more than men in the labor market, the opposite seems to be true in education.

Jon Valant — Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: When I look back on the last year in education, my first reaction is sadness. It’s just been a very hard year on so many students, educators, and parents across the country.

Jon Valant — Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: When I look back on the last year in education, my first reaction is sadness. It’s just been a very hard year on so many students, educators, and parents across the country.

Looking through a policy lens, though, I’m struck by the timing and what that timing might mean for the future of education. Before the pandemic, enthusiasm for the education reforms that had defined the last few decades—choice and accountability—had waned. It felt like a period between reform eras, with the era to come still very unclear. Then COVID-19 hit, and it coincided with a national reckoning on racial injustice and a wake-up call about the fragility of our democracy. I think it’s helped us all see how connected the work of schools is with so much else in American life.

We’re in a moment when our long-lasting challenges have been laid bare, new challenges have emerged, educators and parents are seeing and experimenting with things for the first time, and the political environment has changed (with, for example, a new administration and changing attitudes on federal spending). I still don’t know where K-12 education is headed, but there’s no doubt that a pivot is underway.

Kenneth K. Wong — Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: The pandemic challenges the current capacity of our public education system to address the widening gap in learning and mental well-being of our diverse student population. There is an urgent need to rebuild an education system that embraces equitable learning opportunity for all. Several actions are critical for the new configuration of our education system.

Kenneth K. Wong — Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: The pandemic challenges the current capacity of our public education system to address the widening gap in learning and mental well-being of our diverse student population. There is an urgent need to rebuild an education system that embraces equitable learning opportunity for all. Several actions are critical for the new configuration of our education system.

- First, state and local leaders must leverage commitment and shared goals on equitable learning opportunities to support student success for all.

- Second, align and use federal, state, and local resources to implement high-leverage strategies that have proven to accelerate learning for diverse learners and disrupt the correlation between zip code and academic outcomes.

- Third, student-centered priority will require transformative leadership to dismantle the one-size-fits-all delivery rule and institute incentive-based practices for strong performance at all levels.

- Fourth, the reconfigured system will need to activate public and parental engagement to strengthen its civic and social capacity.

- Finally, public education can no longer remain insulated from other policy sectors, especially public health, community development, and social work.

These efforts will strengthen the capacity and prepare our education system for the next crisis—whatever it may be.

Commentary

Coronavirus and schools: Reflections on education one year into the pandemic

March 12, 2021