Let’s start with the good news: Last year, the global economy defied expectations in potentially history-making ways. Amid wretched conditions—wars, surging inflation, and the biggest interest-rate surge in 40 years—the global economy did not suffer a significant downturn. It merely slowed. This was an unfamiliar plotline: It implies the world economy has grown more resilient in ways we might not yet fully understand.

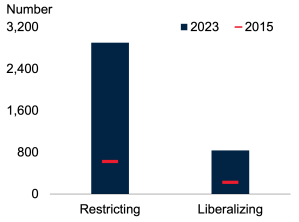

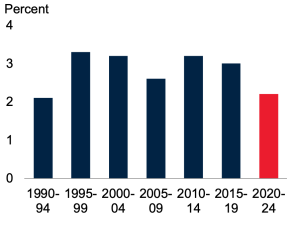

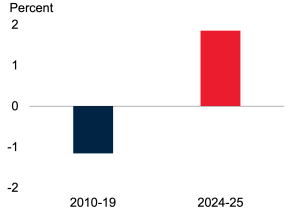

Yet it would be a mistake to think the danger has passed. The World Bank’s latest “Global Economic Prospects” report predicts that global growth will slow to 2.4% in 2024 before edging up to 2.7% in 2025 (Figure 1.A). That might be a reason to cheer—if avoiding another global recession is all you care about. It could be cold comfort for nearly everyone else. Our forecasts imply that global growth remains far short of the strength needed to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by the end of this decade. In fact, the first half of the 2020s is already proving to be the weakest half-decade of growth the global economy has registered in at least 30 years (Figure 1.B).

Figure 1. Global growth

A. Global GDP growth: 2021-24

B. Global GDP growth over time

Source: World Bank.

Note: Global GDP is calculated using real U.S. dollar GDP weights at average 2010-19 prices and market exchange rates.

For now, our near-term forecasts suggest a “soft landing” is becoming increasingly likely. But watch out for wind shear. There are at least five major risks that could threaten the global economy if they materialize:

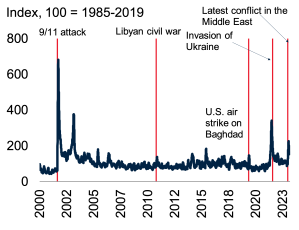

1. Rising geopolitical tensions

Geopolitical tensions have become the single most important risk confronting the global economy (Figure 2.A). Wars are now raging in two regions critical to the world’s food and energy supply—Eastern Europe and the Middle East. An escalation of the conflict in the Middle East could push energy markets into uncharted territory given that the region accounts for nearly 30% of global oil production. Recent attacks in the Red Sea have already disrupted shipping through the Suez Canal, which accounts for 30% of global container traffic.

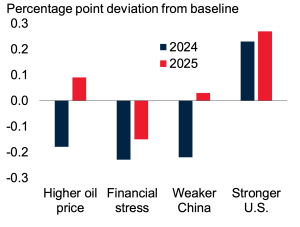

Geopolitical tensions heighten uncertainty, which hurts investment and economic growth. Conflicts and wars also tend to reduce global supply capacity—with potentially inflationary effects. Oil prices are expected to decline this year. However, if the conflict in the Middle East escalates, oil prices could increase by 30% above our baseline forecast of $81 a barrel in 2024. This could stoke global inflation and reduce global growth by 0.2 percentage point (Figure 2.B).

Figure 2. Geopolitical risks and global growth outcomes

A. Geopolitical risk index and conflicts

B. Changes in global growth under alternative risk scenarios

Sources: Caldara and Iacoviello (2022); Oxford Economics; World Bank. A. Last observation is December 11, 2023; B. Panel shows the deviation in global growth under alternative scenarios relative to the baseline.

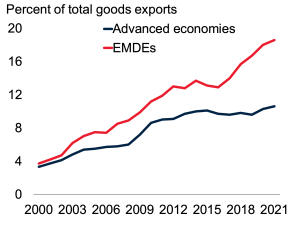

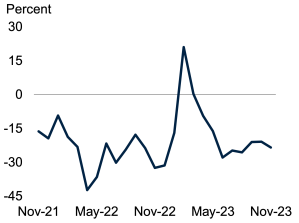

2. China’s economic slowdown

At 4.5%, Chinese growth this year would be the slowest since 1990, outside of the COVID-19 era. That will likely hurt the large number of advanced and developing economies that depend on trade with China. A deeper slowdown would intensify the pain. At the end of 2021, China was the destination for nearly 20% of all goods exports from developing economies—roughly five times the share at the start of this century (Figure 3.A). China has also become a much more important source of demand for commodities—particularly those that are central to the green-energy transition. Our growth forecast for China is subject to downside risks, particularly relating to stresses in the property sector (Figure 3.B). If China were to grow 1 percentage point slower than expected in 2024, global growth could be lower by about 0.2 percentage points, with considerable harm to commodity-exporting developing economies (Figure 2.B).

Figure 3. China: Share of goods exports and property sales

A. Share of goods exports to China

B. Property sales growth in China

Sources: Haver Analytics; National Bureau of Statistics of China; UN Comtrade (database); World Bank. A. EMDEs refer to emerging market and developing economies. Figure shows the share of advanced-economy and EMDE goods exports destined to China. Last observation is 2021.; B. Year-on-year growth of sales, by volume, of residential building floor space. Last observation is November 2023.

3. Surging financial stress

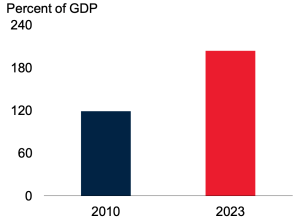

It’s remarkable that the sharpest increase in global interest rates in 40 years so far hasn’t caused the type of havoc we saw in the 1980s. Policy interest rates will likely come down this year, but it might not be fast enough for some countries. After staying negative for an extended time, global real interest rates—nominal rates adjusted for inflation—are now positive and will likely remain elevated for the foreseeable future (Figure 4.A). Against the backdrop of weak growth, that will mean a continuing pressure-cooker environment for developing economies with weak credit ratings. At the end of 2023, the number of developing economies in debt distress was at the highest level since 2000. The combination of weak growth, high real interest rates, and elevated debt levels could make servicing debt more difficult in vulnerable developing economies and push more of them into financial stress (Figure 4.B). A flare-up in financial stress in developing economies could reduce global growth by about 0.2 percentage point this year (Figure 2.B). It would reduce growth in developing economies by 0.6 percentage point.

Figure 4. Real interest rates and debt

A. Global real interest rates

B. Total debt in EMDEs

Sources: Haver Analytics; Kose et al. (2021); U.S. Federal Reserve System; World Bank. A. Figure shows U.S. real interest rates, as calculated using federal fund target rate minus CPI inflation. For 2024-25, the rates are calculated using the projections by the Federal Open Market Committee in December 2023; B. EMDEs refer to emerging market and developing economies. The aggregate is calculated using nominal GDP in U.S. dollars as weights. Total debt is defined as a sum of government and private debt. Data for 2023 are estimates.

4. Trade fragmentation

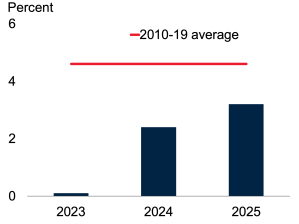

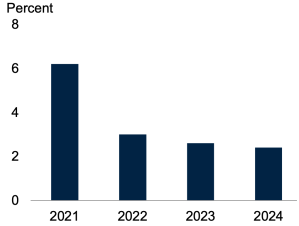

The number of policy measures restricting trade increased sharply last year (Figure 5.A). Trade restrictions and “friend-shoring” and “near-shoring” might seem like logical policy responses to national security concerns. However, such policies could postpone the rebound that is much needed in global trade. In 2023, global trade growth all but ground to a halt—at 0.2%, it was the weakest performance outside of a global recession in 50 years (Figure 5.B). Global trade growth is expected to rebound this year, but it will be only half the average in the decade before the pandemic. Some businesses in advanced economies are retreating from global value chains and diverting investment instead to domestic or regional supply chains. These trends bode ill for developing economies, for whom trade has been a key force for greater productivity and improved living standards.

Figure 5. Trade policy measures and global trade growth

A. New trade measures

B. Global trade growth

B. Global trade growth

Sources: Global Trade Alert; World Bank. A. Number of implemented trade policy interventions since November 2008. Restricting (Liberalizing) measures are interventions that discriminate against (benefit) foreign commercial interests. Reporting-lag adjusted statistics as of December 31, 2023; B. Trade is measured as the average of export and import volumes of goods and services.

Sources: Global Trade Alert; World Bank. A. Number of implemented trade policy interventions since November 2008. Restricting (Liberalizing) measures are interventions that discriminate against (benefit) foreign commercial interests. Reporting-lag adjusted statistics as of December 31, 2023; B. Trade is measured as the average of export and import volumes of goods and services.

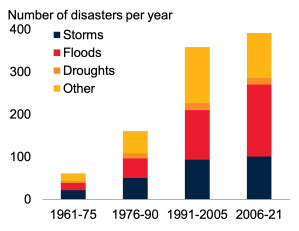

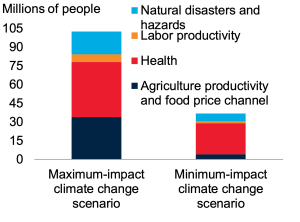

5. Climate change

Conflict in the Middle East has constricted one key chokepoint for global trade. Climate change has squeezed the other. Because of drought-depleted water levels in the Panama Canal, the number of ships transiting through the canal has declined significantly over the past year. That illustrates the degree to which climate change has become a near-term risk, not just a medium-term hazard. 2023 was the hottest year on record. A series of droughts, floods, and wildfires also made the impact of climate change more visible around the world last year. Climate change is increasing the frequency and cost of natural disasters, which tend to crimp economic growth, aggravate poverty, and lower agricultural yields (Figure 6). Damages and risks associated with climate change will cast a long shadow over the global economy this year and next.

Figure 6. Natural disasters and impact of climate change on poverty

A. Natural disasters

B. Impact of climate change on extreme poverty by 2030

Sources: EM-DAT (database); Jafino et al. (2020); World Bank. A. Figure shows total number of disasters per year across all countries in the world; B. Number of additional people in extreme poverty in 2030 owing to climate change.

Each of these risks could amplify others. Intensifying conflict could spark a surge in oil prices that could result in a financial crisis in some countries.

And yet—there is also room for a sweet surprise: The U.S. economy, which almost single-handedly staved off a global recession last year, could outperform yet again in 2024. Our forecasts call for the U.S. economy to grow 1.6% in 2024 and 1.7% in 2025. But if the U.S. labor market merely remains as resilient as it has been since late 2020, U.S. growth could be half a percentage point stronger in 2023 and 0.7 point stronger in 2025. The result would be much stronger global growth as well. If this happens without reigniting inflationary pressures, that would be the icing on the cake.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

5 major risks confronting the global economy in 2024

January 17, 2024