CHAPTER 8

TRANSPARENCY

Technology can address supply chain visibility to bolster human rights, resilience, and sustainability

Nowhere is the economic integration of North America more apparent than in its supply chains. These intertwining manufacturing and logistical connections cross the continent with all the complexity and economic significance of the railroads that began binding the North American continent two centuries ago.

In terms of gross volume, the three North American nations are one another’s most important trading partners: Upwards of 70 percent of exports from Mexico1 and Canada2 are imported into the U.S. Moreover, of the total U.S. intermediate good imports in 2020, almost one-fourth came from Mexico and Canada, with the two countries as the leading export destinations of intermediate goods coming from the U.S.3 Today, supply chains bring auto parts from Guanajuato to Detroit, Iowa corn to Edmonton markets, and aircraft engines made in Ontario to Mexican assembly plants, to name a few examples. The three North American nations constitute a shared production platform on a continental scale.

Supply chains bind North America together, but they have also become a focal point for substantial concern. Three areas deserve special attention:

First, forced labor and other human rights abuses are embedded in global supply chains, including in North America. The International Labour Organization estimates that upwards of 40 million workers are subject to some form of involuntary labor worldwide.4 The goods these workers produce find their way into global supply chains—becoming part of North Americans’ diets,5 clothes,6 cars,7 and more. Without shared visibility, however, it has often been impossible for the public and private sectors to look into opaque supply chains and identify forced labor or other human right abuses.

By building a common operating picture for government and private sector actors alike, regulators can pinpoint transactions from entities potentially involved in forced labor, stopping these goods at the continental border.

Second, modern supply chains are geographically dispersed and imbalanced. Productive capacity is often far removed from end markets, and products are subject to disruption at multiple points along the journey from raw input to final good. The COVID-19 pandemic painfully revealed how the widespread adoption of low-inventory, decentralized, “just in time” supply chains has introduced systemic risk to the entire global economy.8 Policymakers, motivated by national security as well as economic concerns, are now seeking to reshore manufacturing capability.9

Finally, supply chains obscure environmental harm due to a failure to account for the full scope of external costs, including carbon emissions. Supply chains of consumer companies generate far greater social and environmental costs than the company’s own operations, accounting for more than 80 percent of greenhouse-gas emissions and more than 90 percent of the impact on air, land, water, biodiversity, and geological resources.10 However, these externalities are not captured or assigned to participants in economic exchanges.10

Central to all of these challenges is a lack of visibility into supply chains. Without this visibility, governments and firms cannot anticipate or mitigate potential problems, or allocate carbon costs in the supply chains. However, advances in information technology are playing a key role in bringing about the visibility needed for supply chains to move from being points of weakness to points of strength.

Technological advances are bringing opaque supply chains into the light.

Supply chains have been the locus of abuses in large part because they are so difficult to understand, and therefore appropriately regulate and manage. Fundamentally, neither the public or private sector has ever been able to view the entire supply chain because vital supply chain data has been dispersed and decentralized. Valid concerns about privacy, intellectual property, and sovereignty have until now prevented supply chain data from being assembled in one place. This means that even if one actor can identify a potential harm, it can’t trace that harm through the supply chain—and therefore can’t address it systematically.

Today, federated learning offers a solution. With federated learning, it is possible to bring machine learning computation directly to siloed data and extract valuable information without compromising security or privacy.

Federated learning works by training centralized machine learning models on decentralized data. Much as autocorrect algorithms on modern cell phones work by training the same models on users’ cell phones without pooling data, it is possible to train algorithms to recognize patterns in trade data without actually comingling sensitive datasets,12 thus improving the models’ performance without violating data sovereignty, confidentiality, or intellectual property concerns.

This privacy-preserving approach enables learning across previously inaccessible data to create a dynamic, intelligent model of the world’s supply chain network that is accessible to regulators, logistics companies, and private enterprise. Federated learning creates the potential to transform the world’s public and non-public supply chain information into an intelligent map through which stakeholders across the supply chain gain visibility, set rules, collaborate, and build trusted networks.

This technology can enable the multi-user collaboration necessary to bring much needed visibility and resilience to supply chains not only in North America, but globally. With this type of visibility, users across governments, logistics companies, and enterprises can work together to identify abuses plaguing supply chains.

North America can be free of forced labor with integrated supply chain visibility.

Abuses such as forced and child labor have been documented around the world in many industries, but nowhere are these abuses more prevalent than in China. For example, the government’s system of Uyghur forced labor has placed more than 1 million individuals of minority background in as many as 1,200 state-run internment camps throughout Xinjiang.13

Since the beginning of 2016, shipments to North American supply chains of products made using Uyghur forced labor have a total value of $350 million.

These internment camps produce goods that make their way into global supply chains. Research has revealed more than 785,000 first-tier trading relationships between Chinese entities tied to forced labor and the rest of the global economy.14 At the next tier of trade, this figure balloons to more than 6.8 million trading relationships.14

Goods derived from Uyghur forced labor continue to enter North American supply chains. Since the beginning of 2016, 253 companies associated with forced labor in Xinjiang sent 68,413 shipments to 1,117 trading partners in the U.S., Mexico, and Canada.16 These shipments have a total value of approximately $350 million, and were sent to 1,117 companies operating across 326 distinct industries—including hotels, medical devices, wholesale of chemical products, animal food manufacturing, and farming.16 Once shipments enter one part of the North American supply chain, the goods they bring can rapidly spread throughout the entire region.

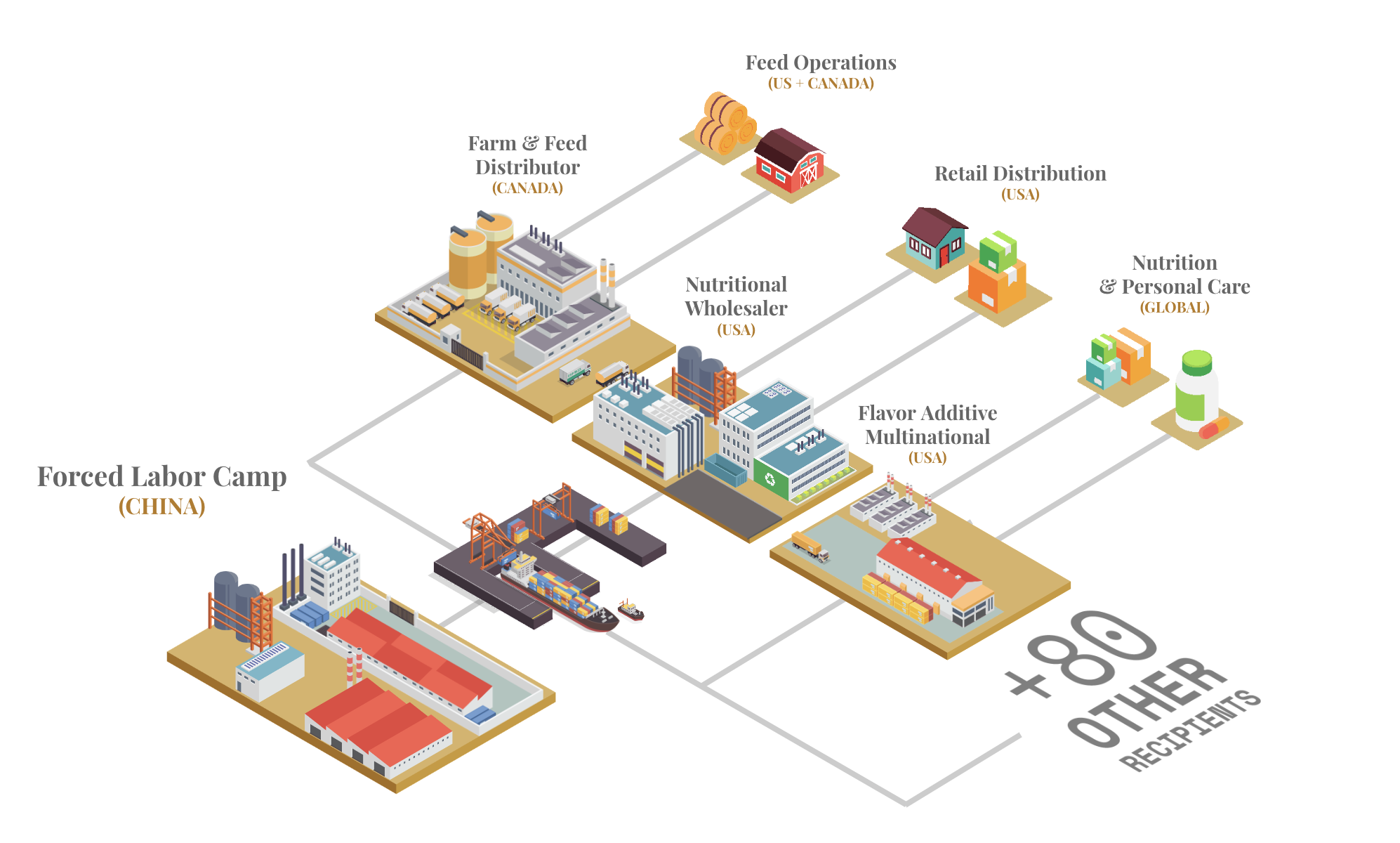

For instance, data show that since the beginning of 2021, a Xinjiang-based producer of food-grade additives, made nearly 700 shipments to 83 separate importers in North America.16 These 83 firms in turn shipped their goods to a combined 82,962 immediate trading partners in North America.16

By building a common operating picture for government and private sector actors alike, regulators can pinpoint transactions from entities potentially involved in forced labor, stopping these goods at the continental border.

Supply chain visibility can help North America reshore key industries and minimize risks.

For the last several decades, North America has offshored much electronics manufacturing to Asia driven by considerations of low cost and working capital optimization. Today, this trend is reversing as business leaders and policymakers look to reshore manufacturing. But unless these plans account for the extended supply chain, moves to reshore production may simply shift dependence.

Today, supply chain visibility can help North America reshore key elements of this manufacturing value chain back into the region without creating additional risk elsewhere.

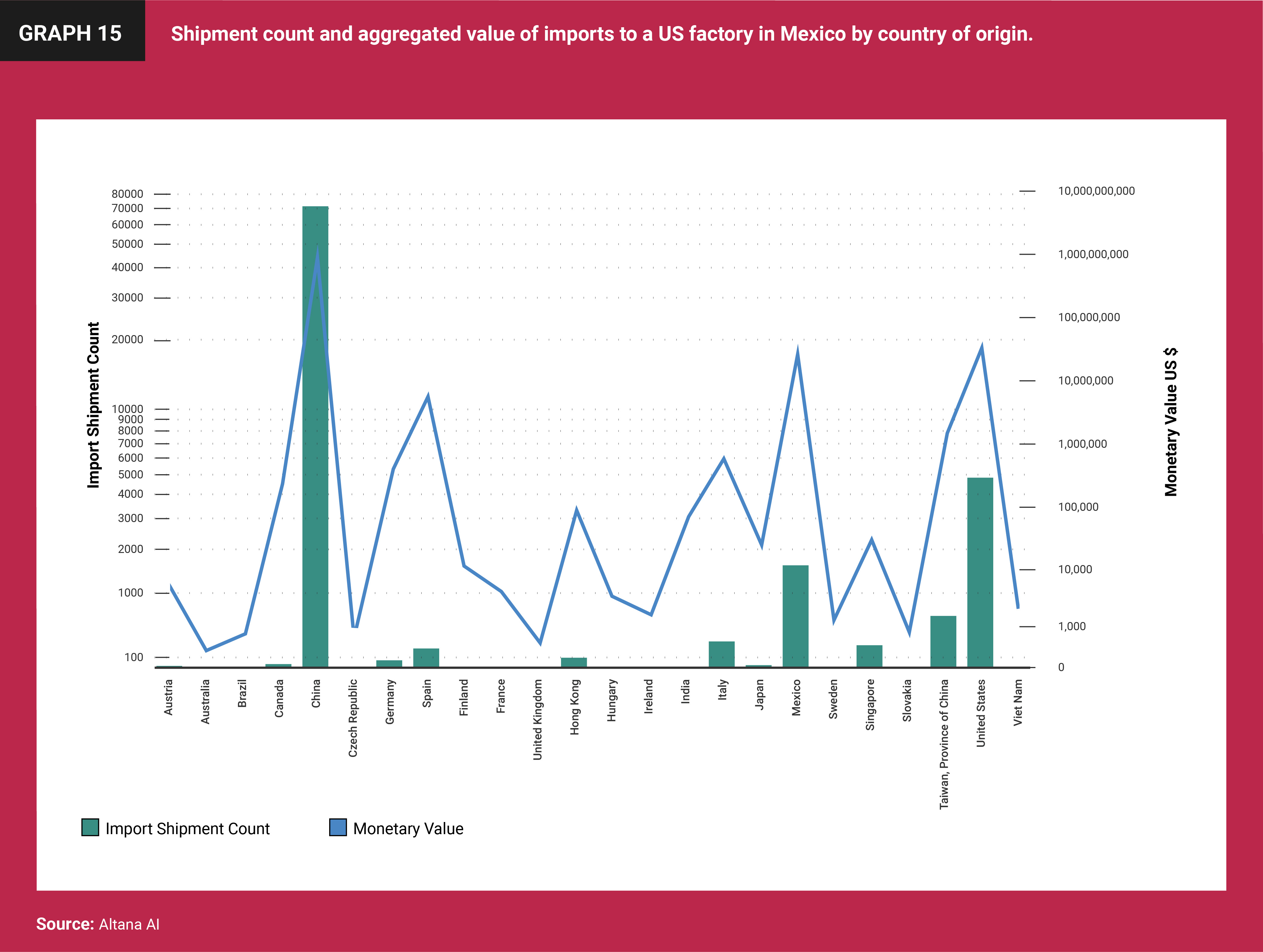

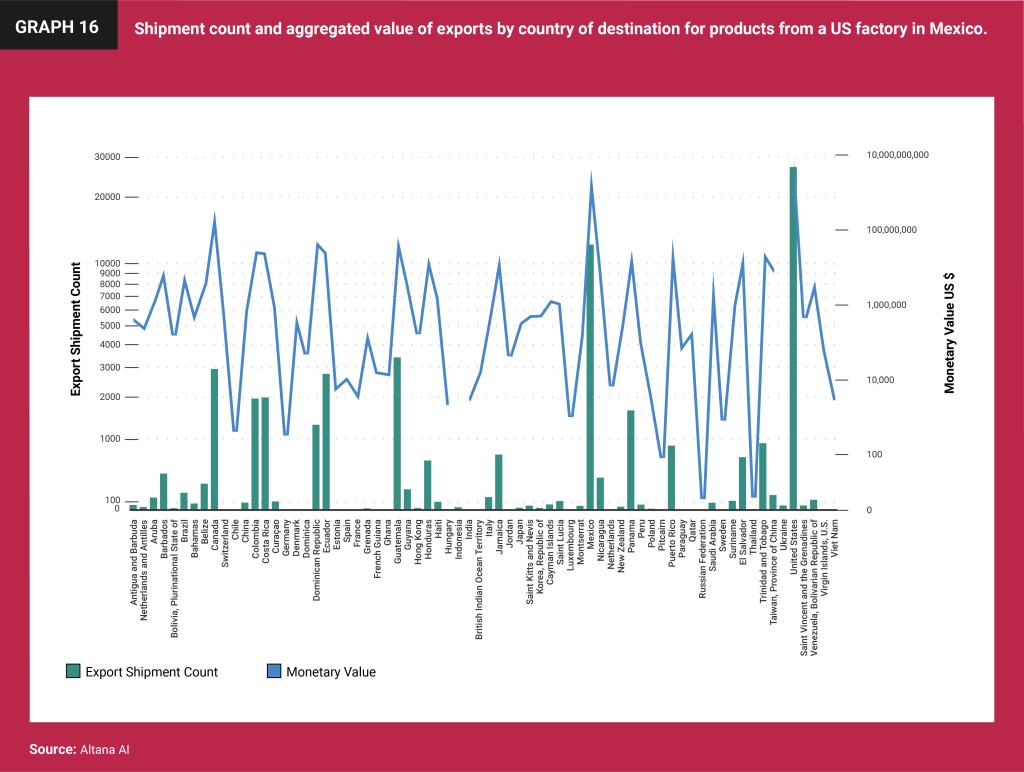

Take, for instance, a particular U.S. company’s manufacturing facilities in Mexico. The company operates manufacturing facilities in three Mexican states; these facilities are key suppliers of household appliances to markets in Canada and the U.S. While on the surface level this production chain appears local to North America, in fact, the Mexican factories rely on second- and third-tier suppliers located in China. With supply chain mapping technology, we can use pooled trade data to better understand the extended supply chain of these facilities, and chart steps that this U.S. company could take to minimize its operational, trade, and compliance risk.

First, we begin by locating the three subsidiary manufacturing facilities.

Second, we use supply chain mapping integrating federated learning to reveal the import and export history of these three facilities.

Next, we can trace the sourcing profile of the American company’s Mexican facilities to see its exposure to China, and to potential forced labor issues. The sourcing profile of the Mexican factories reflects that Chinese-origin suppliers account for more than 70 percent of total shipments of parts to the U.S. company’s factories in Mexico.

Third, regarding the impact on the North American market, the export activities of the U.S. company’s three subsidiary factories in Mexico reveal that the large majority of the refrigerators, stoves, washing machines, and other finished products—nearly 70 percent— are sent to the U.S., with the remainder sent to other countries in the Americas.20

Moreover, the data reveals that this supply chain intersects with specific entities now listed by the U.S. government as employing Uyghur forced labor.21 Data show that the U.S. company maintained a trading relationship with Hefei Meiling Co. Ltd from 2016 to 2020, importing hundreds of horizontal box-type freezers, electrical parts for refrigerators (such as thermostats), and electric cables for appliances. The vast majority of these shipments were made to one specific factory in Mexico, which manufactures refrigerators, washers, components, and plastics for onward export throughout North America.

Supply chain visibility is essential to combatting climate change.

Supply chains are critical for combating climate change. Depending on the sector, upwards of 90 percent of the carbon footprint of a given product is within supply chains, rather than embodied in the final good itself.22 Today, the European Union is moving to require disclosures related to carbon emissions23 and deforestation exposure.24 The U.S. government is considering similar policies.25 Multi-tier supply chain visibility can help in these efforts by showing how environmental harms, such as deforestation caused by industrial agriculture,26 manifest themselves within global supply chains.

Recently, for example, Brazil has identified Porto Velho in Rondônia as a priority municipality for deforestation enforcement and monitoring.27 With multi-tier trade data visibility, we can track exports from this deforestation hotspot.

Trade records from the Altana Atlas show that exporters from Porto Velho have continued to send large volumes of wood, as well as beef and soybeans, to markets in the U.S., Mexico, and Canada. One large meat company, whose facilities in Porto Velho and elsewhere have been linked to deforestation,28 has exported thousands of cartons of beef products directly from Porto Velho to the U.S. since the beginning of 2021.29

Trade data shows that this company also has sent cowhides to a facility owned by a large leather processing company in Guanajuato, Mexico as recently as June 2022. This Mexican facility, in turn, has sent leather goods to a significant number of companies around the U.S. and Canada, including those operating in New Jersey, North Carolina, and Texas.

These supply chains often feature complex transshipment patterns. For instance, in this case, the first Guanajuato facility also sent leather goods to another factory in Guanajuato, which then supplies products to large-scale retail customers throughout the U.S.

The foregoing pertains to just one example of an extended, multinational value chain linked to deforestation.

With extended visibility over supply chains, the three nations of North America can better monitor their exposure to climate change, and over time, implement more rigorous standards for Scope 3 emissions tracking.

Conclusion

Supply chains are the places where our continent connects—but they can be so much more. Rather than shrouding problems like forced labor, fragile production capabilities, or sources of unaccounted for carbon, they can be transparent, reliable, and sustainable avenues of trade. This is the promise of visible supply chains—which can power further success for North America. Realizing the full potential of the North American shared production platform will require understanding and action not only from the continent’s political leaders, but also from those that directly build its supply chains: business leaders, manufacturers, freight forwarders, builders, and businesspeople who manage and maintain the continental economy. With technology, we can bring these disparate actors into view, making our supply chains more secure, more sustainable, and more equitable.

Endnotes

- 1. https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/MEX/Year/LTST/Summarytext

- 2. https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/CAN/Year/LTST/Summarytext

- 3. World Trade Organization, Trade in Value Added and Global Value Chains. US_e.pdf (wto.org)

- 4. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/forced-labour/lang–en/index.htm

- 5. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/our-work/child-forced-labor-trafficking/child-labor-cocoa

- 6. https://www.ecotextile.com/2022100329886/social-compliance-csr-news/new-us-list-highlights-forced-labour-risks.html

- 7. https://www.wsj.com/articles/tesla-gm-among-car-makers-facing-senate-inquiry-into-possible-links-to-uyghur-forced-labor-11671722563

- 8. https://executiveeducation.wharton.upenn.edu/thought-leadership/wharton-at-work/2021/08/rethinking-your-supply-chain/

- 9. Policymakers in the United States, the European Union, and Japan have all created policy roadmaps designed to encourage re-shoring of manufacturing capabilities. See, inter alia, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/02/24/the-biden-harris-plan-to-revitalize-american-manufacturing-and-secure-critical-supply-chains-in-2022/; https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2021)698815; https://static1.squarespace.com/static/595c8a62c534a55db93b722e/t/5f436047381f2c334d61c719/1598251083493/CCE+Japon+Study+Relocation+%28Juillet+2020%29+1.pdf; https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/09/29/us-china-technology-it-supply-chains-manufacturing-decoupling-reshoring-friend-shoring-chips-act/

- 10. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/starting-at-the-source-sustainability-in-supply-chains

- 11. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/starting-at-the-source-sustainability-in-supply-chains

- 12. https://ai.googleblog.com/2020/05/federated-analytics-collaborative-data.html

- 13. https://www.state.gov/forced-labor-in-chinas-xinjiang-region/

- 14. https://www.altana.ai/blog/illuminating-xinjiang-forced-labor-ecosystem

- 15. https://www.altana.ai/blog/illuminating-xinjiang-forced-labor-ecosystem

- 16. Altana Atlas

- 17. Altana Atlas

- 18. Altana Atlas

- 19. Altana Atlas

- 20. Altana Atlas

- 21. Hefei Meiling has a well-established history of connections with forced labor. According to information from the US State Department, the firm was reported to have transferred 1,554 workers from Xinjiang, China to factories including Hefei Meiling’s plant in Anhui province. In 2020, this company was added to the US Department of Commerce’s Entity List after being found to have contributed to “human rights violations and abuses in the implementation of China’s campaign of repression, mass arbitrary detention, forced labor and high-technology surveillance against Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other members of Muslim minority groups in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.”

- 22. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/starting-at-the-source-sustainability-in-supply-chains

- 23. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20221107IPR49611/sustainable-economy-parliament-adopts-new-reporting-rules-for-multinationals

- 24. https://news.mongabay.com/2022/09/european-bill-passes-to-ban-imports-of-deforestation-linked-commodities/#:~:text=European%20 bill%20passes%20to%20ban%20imports%20of%20deforestati-on%2Dlinked%20commodities,-by%20Andr%C3%A9%20Schr%C3%B6der&text=Imports%20of%2014%20types%20of,a%20bill%20passed%20on%20Sept.

- 25. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2022/04/22/executive-order-on-strengthening-the-nations-forests-communities-and-local-economies/

- 26. https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2022-beef-industry-fueling-amazon-rainforest-destruction-deforestation/

- 27. https://www.gov.br/mma/pt-br/assuntos/servicosambientais/ controle-de-desmatamento-e-incendios-florestais/pdf/Listagemmunicpiosprioritriosparaaesdepreveno2021.pdf

- 28. https://unearthed.greenpeace.org/2022/11/11/jbs-cattle-brazils-biggest-deforester-amazon/

- 29. https://altana-main.cloud.databricks.com/?o=31355770351799#notebook/1036880522630853/command/3219636688912813