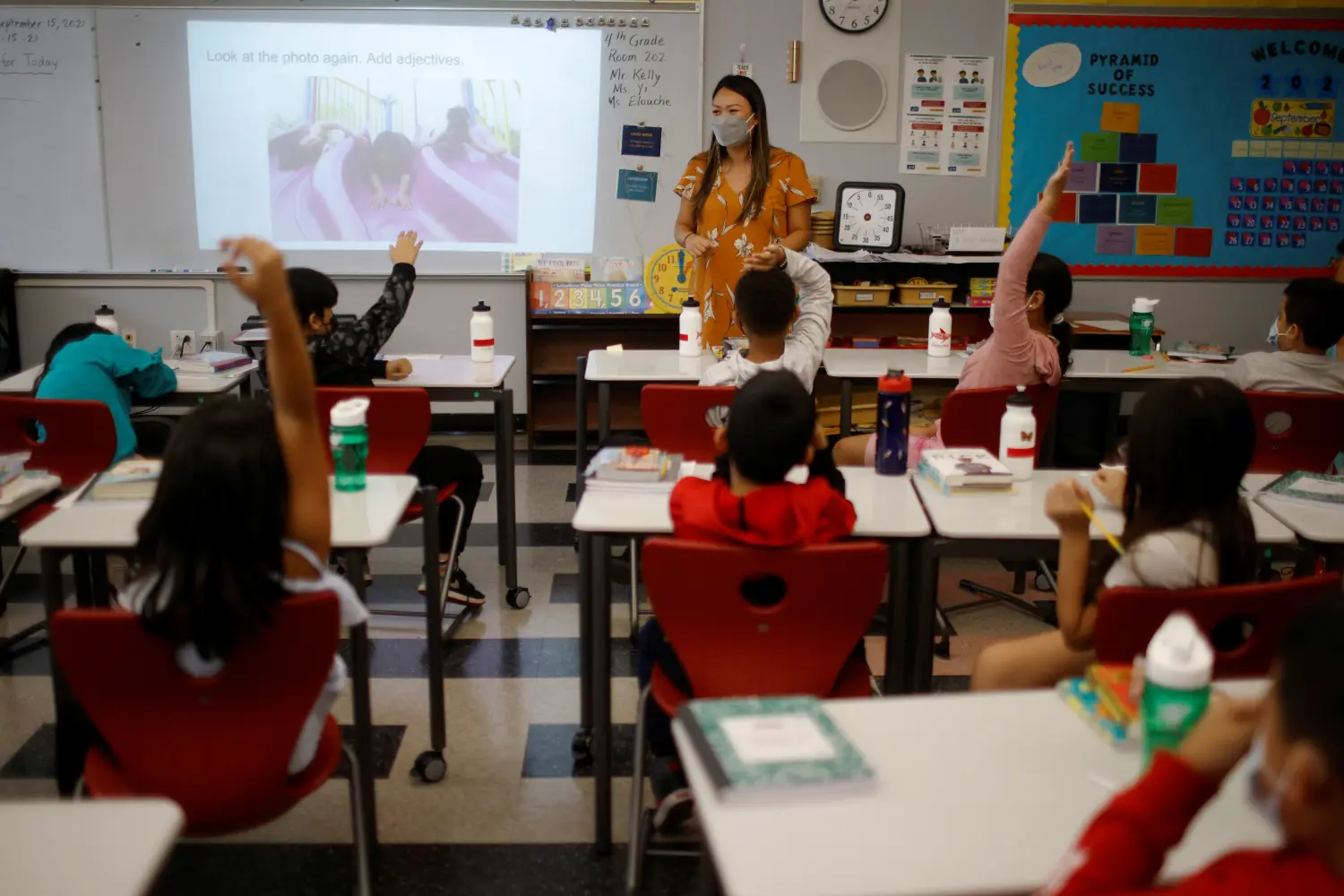

Entering 2022, the world of education policy and practice is at a turning point. The ongoing coronavirus pandemic continues to disrupt the day-to-day learning for children across the nation, bringing anxiety and uncertainty to yet another year. Contentious school-board meetings attract headlines as controversy swirls around critical race theory and transgender students’ rights. The looming midterm elections threaten to upend the balance of power in Washington, with serious implications for the federal education landscape. All of these issues—and many more—will have a tremendous impact on students, teachers, families, and American society as a whole; whether that impact is positive or negative remains to be seen.

Below, experts from the Brown Center on Education Policy identify the education stories that they’ll be following in 2022, providing analysis on how these issues could shape the learning landscape for the next 12 months—and possibly well into the future.

Daphna Bassok — Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: As an early childhood policy researcher (and a mom of two children who have spent the early part of this new year without child care due to snow), I am totally focused on child-care policy. When done right, child care can serve two critical roles: simultaneously providing learning opportunities for young children, and essential work supports for families. In the United States, however, we have structured and funded child care in ways that make it extremely difficult for child-care providers to succeed on either front. While we offer free public education to children starting at age 5, families of younger children are left to navigate a complex, fragmented system—one with far fewer public options as well as costs that create real burdens. The pandemic exacerbated these longstanding challenges. In 2022, through the White House’s Build Back Better plan, we have the chance to significantly improve access to early learning opportunities and build a more coordinated, high-quality system. I’ll be tracking that bill closely. My hope is that, if it’s passed, I’ll be following the impacts of these historic investments on children, educators, families, and the economy.

Daphna Bassok — Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: As an early childhood policy researcher (and a mom of two children who have spent the early part of this new year without child care due to snow), I am totally focused on child-care policy. When done right, child care can serve two critical roles: simultaneously providing learning opportunities for young children, and essential work supports for families. In the United States, however, we have structured and funded child care in ways that make it extremely difficult for child-care providers to succeed on either front. While we offer free public education to children starting at age 5, families of younger children are left to navigate a complex, fragmented system—one with far fewer public options as well as costs that create real burdens. The pandemic exacerbated these longstanding challenges. In 2022, through the White House’s Build Back Better plan, we have the chance to significantly improve access to early learning opportunities and build a more coordinated, high-quality system. I’ll be tracking that bill closely. My hope is that, if it’s passed, I’ll be following the impacts of these historic investments on children, educators, families, and the economy.

Stephanie Cellini — Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: In 2022, I will be following several debates over federal higher-education policy that could bring sweeping changes for colleges, students, and the market for higher education more generally. First, the Biden administration recently extended the pandemic-induced pause in student-loan payments to May 1, 2022. It is unclear whether payments will restart at that time, or whether further extensions or student-loan cancellation may follow.

Stephanie Cellini — Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: In 2022, I will be following several debates over federal higher-education policy that could bring sweeping changes for colleges, students, and the market for higher education more generally. First, the Biden administration recently extended the pandemic-induced pause in student-loan payments to May 1, 2022. It is unclear whether payments will restart at that time, or whether further extensions or student-loan cancellation may follow.

I will also be watching the Department of Education’s negotiated rulemaking sessions and following any subsequent regulatory changes to federal student-aid programs. I expect to see changes to income-driven repayment plans and will be monitoring debates over regulations governing institutional and programmatic eligibility for federal student-loan programs. Notably, the Department of Education will be re-evaluating Gainful Employment regulations—put in place by the Obama administration and rescinded by the Trump administration—which tied eligibility for federal funding to graduates’ earnings and debt.

Michael Hansen — Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: This year, I’ll be paying close attention to substitute staffing and related policy responses. The pandemic has stretched school resources and personnel in many ways. Thankfully, recession-induced budget cuts were avoided thanks to quick legislative action and schools have been able to keep their teacher workforces largely intact. But this does not mean that all staffing has been easy. As many front-line positions in the economy have received pay increases, school systems have found it harder to keep many of their operational jobs—which are often low-paying—including janitors, bus drivers, aides, and others.

Michael Hansen — Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: This year, I’ll be paying close attention to substitute staffing and related policy responses. The pandemic has stretched school resources and personnel in many ways. Thankfully, recession-induced budget cuts were avoided thanks to quick legislative action and schools have been able to keep their teacher workforces largely intact. But this does not mean that all staffing has been easy. As many front-line positions in the economy have received pay increases, school systems have found it harder to keep many of their operational jobs—which are often low-paying—including janitors, bus drivers, aides, and others.

But the biggest and most concerning hole has been in the substitute teacher force—and the ripple effects on school communities have been broad and deep. Based on personal communications with Nicola Soares, president of Kelly Education, the largest education staffing provider in the country, the pandemic is exacerbating several problematic trends that have been quietly simmering for years. These are: (1) a growing reliance on long-term substitutes to fill permanent teacher positions; (2) a shrinking supply of qualified individuals willing to fill short-term substitute vacancies; and, (3) steadily declining fill rates for schools’ substitute requests. Many schools in high-need settings have long faced challenges with adequate, reliable substitutes, and the pandemic has turned these localized trouble spots into a widespread catastrophe. Though federal pandemic-relief funds could be used to meet the short-term weakness in the substitute labor market (and mainline teacher compensation, too), this is an area where we sorely need more research and policy solutions for a permanent fix.

Douglas N. Harris — Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: I’ll be following three connected stories in 2022.

Douglas N. Harris — Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: I’ll be following three connected stories in 2022.

First, what’s to come of the vaccine for ages 0-4? This is now the main impediment to resuming in-person activity. This is the only large group that currently cannot be vaccinated. Also, outbreaks are triggering day-care closures, which has a significant impact on parents (especially mothers), including teachers and other school staff.

Second, will schools (and day cares) require the vaccine for the fall of 2022? Kudos to my hometown of New Orleans, which still appears to be the nation’s only district to require vaccination. Schools normally require a wide variety of other vaccines, and the COVID-19 vaccines are very effective. However, this issue is unfortunately going to trigger a new round of intense political conflict and opposition that will likely delay the end of the pandemic.

Third, will we start to see signs of permanent changes in schooling a result of COVID-19? In a previous post on this blog, I proposed some possibilities. There are some real opportunities before us, but whether we can take advantage of them depends on the first two questions. We can’t know about these long-term effects on schooling until we address the COVID-19 crisis so that people get beyond survival mode and start planning and looking ahead again. I’m hopeful, though not especially optimistic, that we’ll start to see this during 2022.

Jon Valant — Director of and Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: We’ve entered 2022 with two wildly important proposals hanging in the balance. For improving educational opportunity and outcomes, it’s hard to find more promising strategies—with more empirical support—than (1) reducing child poverty and (2) increasing access to high-quality pre-K. The expansion of the Child Tax Credit (CTC) via the American Rescue Plan sharply reduced child poverty. Failing to extend the CTC would mean reversing that progress and missing a rare opportunity to help our most vulnerable kids. Meanwhile, the U.S. has underinvested in early childhood education (ECE); without federal intervention, it’s hard to imagine making much progress on issues like terribly low pay (and correspondingly high turnover) for ECE teachers.

Jon Valant — Director of and Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: We’ve entered 2022 with two wildly important proposals hanging in the balance. For improving educational opportunity and outcomes, it’s hard to find more promising strategies—with more empirical support—than (1) reducing child poverty and (2) increasing access to high-quality pre-K. The expansion of the Child Tax Credit (CTC) via the American Rescue Plan sharply reduced child poverty. Failing to extend the CTC would mean reversing that progress and missing a rare opportunity to help our most vulnerable kids. Meanwhile, the U.S. has underinvested in early childhood education (ECE); without federal intervention, it’s hard to imagine making much progress on issues like terribly low pay (and correspondingly high turnover) for ECE teachers.

The CTC and universal pre-K top my list for 2022, but it’s a long list. I’ll also be watching the Supreme Court’s ruling on vouchers in Carson v. Makin, how issues like critical race theory and detracking play into the 2022 elections, and whether we start to see more signs of school/district innovation in response to COVID-19 and the recovery funds that followed.

Kenneth K. Wong — Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: State-level governance will offer opportunities and challenges for educational progress in 2022. Education policy will be influenced by the substance and rhetoric in the electoral process across states throughout this year. Of the 36 gubernatorial races, at least five Republican incumbents and three Democratic incumbents have decided not to run for re-election. Fifteen states will hold elections for either the school chief, such as California and Arizona, or state board members, such as Ohio. Races for state legislators will determine the magnitude of single-party dominance, meaning one party has control over the governorship and the two chambers of the state legislature (aside from Nebraska, which has a unicameral legislature). Currently, the Republican Party and the Democratic Party dominate 23 and 15 state governments, respectively.

Kenneth K. Wong — Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Brown Center on Education Policy: State-level governance will offer opportunities and challenges for educational progress in 2022. Education policy will be influenced by the substance and rhetoric in the electoral process across states throughout this year. Of the 36 gubernatorial races, at least five Republican incumbents and three Democratic incumbents have decided not to run for re-election. Fifteen states will hold elections for either the school chief, such as California and Arizona, or state board members, such as Ohio. Races for state legislators will determine the magnitude of single-party dominance, meaning one party has control over the governorship and the two chambers of the state legislature (aside from Nebraska, which has a unicameral legislature). Currently, the Republican Party and the Democratic Party dominate 23 and 15 state governments, respectively.

Electoral dynamics will affect several important issues: the selection of state superintendents; the use of American Rescue Plan funds; the management of safe return to in-person learning for students; the integration of racial justice and diversity into curriculum; the growth of charter schools; and, above all, the extent to which education issues are leveraged to polarize rather than heal the growing divisions among the American public.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).