Artificial intelligence has the potential to transform local economies. Hype and fear notwithstanding, many experts forecast various forms of AI to become the source of substantial economic growth and whole new industries. Ultimately, AI’s emerging capabilities have the potential to diffuse significant productivity gains widely through the economy, with potentially sizable impacts.

Yet even as American companies lead the way in pushing AI forward, the U.S. AI economy is far from evenly distributed. In fact, as we found in a recent report, AI development and adoption in the United States is clustered in a dangerously small number of metropolitan centers.

Our research suggests that while some AI activity is distributed fairly widely among U.S. regions, a combination of first-mover advantage, market-concentration effects, and the “winner-take-most” dynamics associated with innovation and digital industries may already be shaping AI activity into a highly concentrated “superstar” geography in which large shares of R&D and commercialization take place in only a few regions. This could lead to a new round of the tech-related interregional inequality that has led to stark economic divides, large gains for a few places, and further entrenchment of a “geography of discontent” in politics and culture.

For that reason, we would argue that the nation should actively counter today’s emerging interregional inequality. Where it can, the government should act now while AI geography may still be fluid to ensure that more of the nation’s talent, firms, and places participate in the initial build out of the nation’s AI economy.

The diffusion of AI

AI and especially machine learning (ML) applications are proliferating rapidly, according to our assessment. Increasingly, AI applications are being utilized in a wide range of industry sectors, from health care, finance, and information technology to sales, marketing, entertainment, and national security. Beyond that, the power and broad applicability of AI’s emerging capabilities ensure that the technology has the potential to transform these industries, adding to their efficiency and capacities. Which is why numerous economists and business scholars believe that AI has the potential to be “the most important general-purpose technology of our era,” as Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee assert.

Which is, in turn, why our report underscores the potential benefits of AI development for a good number of the nation’s regional economies. If it spreads in a favorable way, AI could become a widespread source of economic development. Indeed, a recent analysis by Nicholas Bloom of Stanford University maps how the diffusion of 29 recent “disruptive technologies” has tended to spread related jobs beyond their “pioneer” regions into more places over time. AI may well follow in kind.

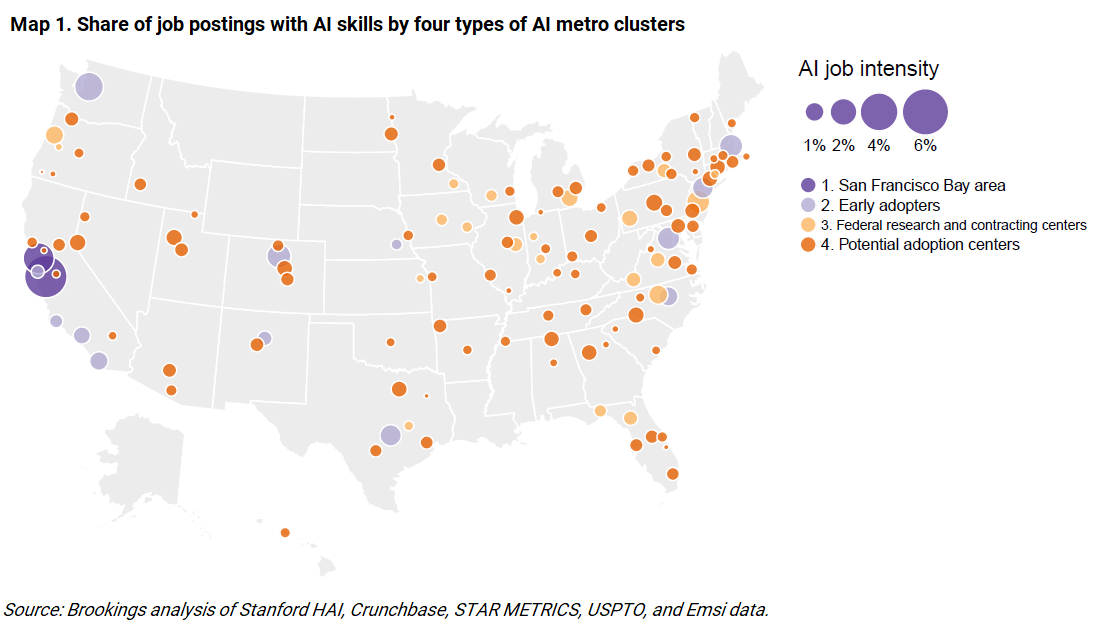

In this vein, it is encouraging that our research suggests that as many as 125 U.S. metros now support at least a modest degree of AI-related research-and-development and/or AI commercial activity.

An even, widespread divergence of AI in the next decade could provide a welcome and widespread source of growth and productivity.

The divergence of AI

And yet, even Nicholas Bloom’s relatively encouraging analysis of tech diffusion emphasizes that the initial “frontier” hubs out of which new technologies emanate tend to dominate the associated industries for decades. Such early hubs with their intense and beneficial “clustering” seem to retain their preeminence.

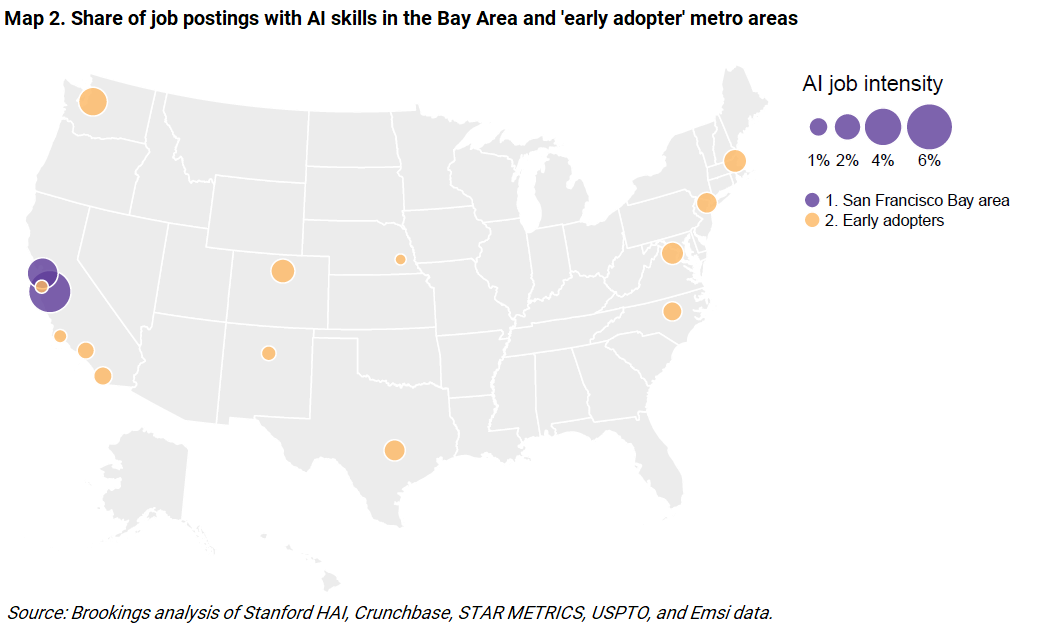

And in fact, our mapping of the current U.S. AI industry suggests that AI activity is already highly concentrated in a short list of “superstar” and “early adopter” hubs, often arrayed along the coasts. These hubs encompass the bulk of the nation’s AI research and commercialization. In this regard, only 36 U.S. metros have developed a substantial AI research or commercial presence. What’s more, just 15 dense agglomerations (two of which are the Bay Area’s San Francisco and San Jose) make up 40% to 50% of the nation’s AI research and 50% to 60% of its AI firms and hiring.

In the interactive tool below, use the drop-down tool to select a metro area and view its AI activity.

Between them, the Bay Area and the early adopter metros dominate the U.S. AI economy. Ranging from Boston, New York, and Washington, D.C., to Austin, Seattle, and the Bay Area, all of these AI hubs possess major research universities that have been successful in building top-tier research programs in AI-related sub-specialties, whether it be at Stanford, the University of California at Berkeley, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Texas, or the University of Washington. Equally important, all of these regions are home either to headquarters or major outposts of leading Big Tech market leaders like Alphabet (Google), Salesforce, Facebook, NVIDIA, Amazon, and CrowdStrike.

Our initial accounting, while not definitive, suggests that the current early development of the U.S. AI sector is trending along a pathway oriented toward a highly concentrated “superstar” geography of dominant hubs set off from much thinner development almost everywhere else.

Countering the winner-take-most dynamic

What should be done to ensure that AI’s benefits are spread more widely and are broadly felt? To be sure, some will say nothing should be done. Some economists argue that a highly concentrated, winner-take-most geography really is the optimal, market-ordained geographical configuration for maximum innovation. In this view, intense “clustering” is believed to support regional and national prosperity, both in the early stage and later on.

And yet, we would suggest that the AI map’s current and likely winner-take-most geography bears scrutiny. We now know that digital advances such as AI build on themselves and can confer impregnable first-mover advantages on fortunate locations. Therefore, we suggest early action to adjust AI’s diffusion trends and nudge them toward a wider flourishing.

For their part, cities and regions can and should instigate their own “bottom-up” strategies to advance their standing in the algorithmic economy. Self-help by cities to build up their local technology and skill capacities and to work with their top local firms to foster the development of unique, industry-pertinent use-cases will always matter.

But beyond that, it has become increasingly clear that “top-down” federal action will be necessary to widen the reach of investments in technologies like AI, with the goal of spreading of high-value economic development. In this vein, the federal government—given its unique reach and relevant program channels—holds both the power and the responsibility to offset excessive concentration with efforts to broaden the AI map.

Some of these efforts should entail broad investments in AI innovation and talent to spur growth across the board. Pending federal legislation with bipartisan support calls for new investments in AI R&D and would begin to establish a national AI research infrastructure that democratizes access to the resources that fuel AI development across the nation, as has been urged by the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence (NSCAI). Yet these investments, if passed into law, would only be a start. The NSCAI report, for example, calls for a doubling of non-defense funding for AI R&D to reach $32 billion per year by 2026. Other pending initiatives in Congress would boost U.S. STEM education and fund thousands of undergraduate- and graduate-level fellowships in fields critical to the AI future—an important start for accelerating U.S. and regional growth.

Beyond these national interventions, federal policy needs to focus intentionally and specifically on boosting AI development in specific, new places. The recent affirmation of place-based interventions to stem regional disparities points the way—and fortunately programs for this work exist or are pending. The National Science Foundation’s National AI Research Institutes program established 11 new institutes this summer, building on the first round of seven in 2020. These institutes will concentrate on critical topics such as improving the quality of health care, making agriculture more resilient, and enhancing adult remote learning. But, equally important, they will promote such leading-edge work in regions far from the usual suspects, where local knowledge spillovers and talent exchanges can contribute to economic growth. The NSF should go further with this program.

By the same token, the current Congress has displayed a new interest in fostering technology-based growth in new places—and should go further with that, with an eye on AI as a transformational technology. Even now, the Economic Development Administration is soliciting proposals from regions to revitalize their economies through its $1 billion Build Back Better Regional Challenge. Ideally, some of the 20 to 30 $25 million to $75 million awards will help up-and-coming regions create or scale up strong new AI clusters in new places. Beyond that, Congress needs to deliver substantial funding to another transformative program now pending: the plan to create a set of larger-scale regional technology hubs, which would help five to 10 promising metro areas become self-sufficient, competitive innovation ecosystems, including for AI. Inspired in part by the Brookings Institution / Information Technology and Innovation Foundation report “The Case for Growth Centers: How to Spread Tech Innovation across America,” the concept has passed the Senate and awaits funding through the pending reconciliation act. That means the United States has the opportunity to take meaningful action—at scale—to nudge five to 10 new metros onto the list of truly substantial AI hubs. It should seize that opportunity.

In sum, the latest and potentially most powerful digital technology yet is growing rapidly with significant power to change the nation’s economic map. Already we have seen how the internet and social media booms have altered the nation’s urban system, creating superstar hubs and many more places left behind. Now, we can either shape the coming changes or let them proceed as they will. Our recommendation is that we invest now to counter AI’s likely winner-take-most tendencies and nudge the emerging industry map toward greater balance.

Mark Muro is a senior fellow and policy director at the Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program.

Sifan Liu a former senior research analyst in the Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program.

Commentary

How to prevent a winner-take-most outcome for the U.S. AI economy

October 6, 2021