In the wake of the 2016 presidential election, many analysts have interpreted Donald Trump’s victory as the product of economic anxiety among the white working class—particularly in the smaller towns and rural areas that provided his electoral margin in closely contested states like North Carolina, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

This piece does not purport to explain why people voted the way they did, or what role economic factors played in their decisions. Rather, it acknowledges that the state of the economy in small-town and rural America highlighted throughout the campaign and after the election surely deserves attention. Economists such as David Autor have chronicled how increasing Chinese imports over the past two decades produced long-term economic dislocation in many of these communities. Anne Case and Angus Deaton uncovered alarming evidence that mortality rates have risen among white Americans with lower levels of education, paralleling a rapid increase in drug overdoses largely concentrated in non-urban areas.

Central to these discussions is the availability of work in such communities, particularly for men who have borne the brunt of manufacturing job losses. Research from President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers highlighted the trends and factors underlying the decline in labor force participation among prime-aged men (ages 25–54). Earlier this year, I examined the metropolitan geography of non-working, prime-aged men, finding that smaller industrial centers in Michigan, Indiana, and Ohio exhibited low rates of male employment, as did mining centers in West Virginia and Louisiana, and agricultural centers in Arkansas, Texas, and inland California.

While the focus on metropolitan areas illustrates important regional patterns relating to economic function and migration, it may obscure important differences in employment within metro areas, while also overlooking the non-metropolitan communities on which economists have focused increasing attention. By examining the full range of U.S. community types, this analysis shows that cities and smaller communities ultimately have a shared interest in improving access to employment opportunities for prime-aged workers.

To illustrate conditions and trends in work across the urban-rural continuum, I examined U.S. Census data for cities and counties according to a novel Brookings Metro classification system1:

- 139 primary cities anchor the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas; they include the largest city in each of those metro areas, along with other cities in the metro name with populations of at least 100,000 (e.g., all three cities named in the Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim metropolitan area).

- 81 high-density suburban counties surround or abut many of these cities; at least 95 percent of residents in these counties live in a census-defined “urbanized area” that forms the dense core of the metropolitan area; these are often referred to as “older” or “first” suburbs (e.g., Alameda, CA; New Haven, CT; Fulton, GA).

- 157 mature suburban counties represent the next era of metropolitan development, where today 75–95 percent of residents live in an urbanized area (e.g., Kendall, IL; Howard, MD; Collin, TX).

- 344 emerging suburban and exurban counties lie at the fringe of major metro areas, where fewer than 75 percent of residents live in urbanized areas (e.g., Fauquier, VA; Aiken, SC; St. Croix, WI).

- 567 small metropolitan counties comprise metropolitan areas outside the 100 largest (e.g., Muskegon, MI; St. Lucie, FL; Pueblo, CO).

- 658 micropolitan counties are part of census-defined micropolitan areas centered on smaller cities and towns with populations between 10,000 and 50,000 people (e.g., Twin Falls, ID; Clinton, NY [Plattsburgh]; Dare, NC [Kill Devil Hills]).

- 1,318 rural counties form the rest of the U.S. map, from Aroostook in northern Maine (population 72,000) to Golden Valley in central Montana (population 880).

Figure 1.

Classifying the United States in this way reveals that primary cities, high-density and mature suburbs, and small metro area counties contain roughly similar numbers of residents (Figure 1). The less urbanized parts of the country contain smaller numbers of people, with rural areas accounting for the smallest share (just 6 percent of total U.S. population).

This view of the urban-rural continuum also points to three key findings regarding the geography of work (and non-work) among prime-aged men in the United States.

Rates of work among prime-aged men are below average in both cities and smaller, less urbanized communities. The latest available data, which reflect conditions between 2010 and 2014, indicate that slightly over 80 percent of all prime-aged men nationwide were working during that time.2 Prevailing rates were lower, however, in both large cities and smaller, less urban communities (Figure 2). In big cities and smaller metro areas, 79 percent of prime-aged men were employed during those years. The shares dropped to 75 and 72 percent, respectively, in micropolitan and rural areas.

Figure 2.

Even among these smaller places, rates of employment among prime-aged men varied across the United States. States beyond just the Rust Belt and Appalachia exhibited low rates of work in their micropolitan and rural areas. In fact, among states with at least 50,000 residents in these types of communities, rates were lowest in Florida, Arizona, and California (Figure 3). In non-metropolitan Louisiana, South Carolina, and Georgia, too, less than two-thirds of prime-aged men were employed in the 2010–2014 period. While Kentucky and West Virginia also exhibited employment rates below 70 percent in their smaller areas, these statistics indicate that even many states with racially and ethnically diverse rural areas suffer employment challenges in such communities.

Low rates of work among prime-aged men also affect many big cities with diverse populations. Among the 139 primary cities, 18 exhibited employment rates below 70 percent for these men from 2010–2014. Interestingly, Rust Belt cities—including three in Ohio and one each in Michigan and Pennsylvania—figure most prominently among those with very low prime-aged male employment rates. Other racially segregated cities in the Northeast (Hartford, Newark, Rochester, Springfield, and Syracuse) exhibit similarly low rates of work among these men.

Figure 3.

Many non-metro communities and cities share low rates of work

| Micropolitan/rural areas in state | Prime-aged male employment rate (2000 to 2010-14) | Primary city | Prime-aged male employment rate (2000 to 2010-14) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Florida | 57.2 | Youngstown, Ohio | 47.6 |

| Arizona | 58.1 | Detroit, Mich. | 51.1 |

| California | 64.5 | Dayton, Ohio | 61.1 |

| Louisiana | 65.5 | Cleveland, Ohio | 62.5 |

| South Carolina | 65.8 | Hartford, Conn. | 62.6 |

| Georgia | 66.5 | Harrisburg, Pa. | 65.6 |

| Kentucky | 66.9 | Syracuse, N.Y.. | 66.0 |

| Mississippi | 69.2 | Newark, N.J. | 66.1 |

| West Virginia | 69.3 | Springfield, Mass. | 66.5 |

| Virginia | 69.9 | Rochester, N.Y. | 67.1 |

| All micropolitan/rural areas | 73.8 | All primary cities | 79.3 |

Source: Brookings analysis of 2010-14 American Community Survey data

Note: States displayed had at least 50,000 micropolitan/rural residents in 2010-14

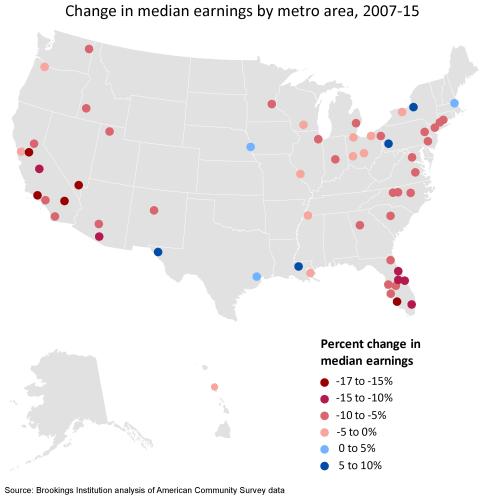

Employment rates among men fell dramatically in smaller communities, but rose in cities. Considerably lower rates of work among prime-aged men in micropolitan and rural areas reflect a long-term decline in their employment. From 2000 to 2010–2014, the share of males ages 25–54 who were employed dropped by 4.8 percentage points in micropolitan counties, and by 5.4 percentage points in rural counties (Figure 4). By contrast, employment among this group in cities rose by 2 percentage points during that time and fell only modestly in high-density suburbs. This suggests that a community’s level of urbanization was closely related to its employment outcomes for prime-aged male workers.

Figure 4.

While industrial Midwestern states did not have particularly low non-metro male employment rates in 2010–2014, many saw those rates fall significantly since 2000. Southern states—including South Carolina, Georgia, and Tennessee—suffered the most dramatic declines, but Michigan, Indiana, and Pennsylvania also registered drops of 6–8 percentage points in the share of their micropolitan and rural prime-aged males in work (Figure 5).

Many cities saw equivalent gains in employment rates among this group, including the largest (New York), second-largest (Los Angeles), and fourth-largest (Houston) cities in the country. Some of the changes in non-metro areas and cities may be attributable to changes in the strength of local economies and their demand for workers. At the same time, the changes may also reflect shifts in the underlying populations of those areas over time, as small communities lose more employable residents to out-migration and big cities gain them through in-migration. Notwithstanding those widespread gains, older industrial cities like Akron, Allentown, Augusta, Detroit, Syracuse, and Tacoma experienced declines in prime-aged male employment similar to those occurring in rural areas nationwide.

Figure 5.

Male employment fell dramatically in many states’ non-metro areas, while it rose dramatically in several big cities

| Micropolitan/rural areas in state | Change in prime-aged male employment rate (2000 to 2010-14) | Primary city | Change in prime-aged male employment rate (2000 to 2010-14) |

|---|---|---|---|

| South Carolina | -9.4 | Miami, Fla. | 12.5 |

| Georgia | -8.9 | Jersey City, N.J. | 10.0 |

| Tennessee | -8.1 | Newark, N.J. | 10.0 |

| Michigan | -7.7 | Los Angeles, Calif. | 8.2 |

| Missouri | -7.7 | McAllen, Texas | 7.8 |

| Florida | -7.6 | Houston, Texas | 7.1 |

| North Carolina | -7.2 | Ontario, Calif. | 7.0 |

| Oregon | -7.1 | Oakland, Calif. | 6.9 |

| Indiana | -6.5 | Oxnard, Calif. | 6.5 |

| Pennsylvania | -6.4 | New York, N.Y. | 6.3 |

| All micropolitan/rural areas | -5.1 | All primary cities | 2.0 |

Source: Brookings analysis of 2000 census and 2010-14 American Community Survey data

Note: States displayed had at least 50,000 micropolitan/rural residents in 2010-14

Big cities remain home to more out-of-work prime-aged men than other types of communities. As shown in Figure 2, prime-aged men in cities exhibited below-average employment rates in 2010–2014, as did those in small metro areas, micropolitan areas, and rural communities. This finding—combined with the fact that primary cities are the most populous of the seven community types analyzed here (see Figure 1)—shows that cities contain a larger number of out-of-work prime-aged men than any other community type (see Figure 6). An estimated 2.9 million non-working males ages 25–54 lived in big cities in 2010–2014. The next-largest group occupied small metro areas, followed by high-density and mature suburbs. If micropolitan and rural areas are considered together, they still contained fewer out-of-work prime-aged men than either primary cities or small metro areas.

Figure 6.

This analysis points to two key takeaways.

First, for as much as the 2016 election pitted urban versus rural interests (reflected in maps of the presidential vote), these places share an important interest in improving the availability and quality of jobs. In the wake of the election, analysis has focused on the white working class and how to alleviate the economic distress facing the smaller communities in which many of those individuals live. But just a year and a half ago, the conversation focused on urban places like Baltimore and Ferguson, where tensions between communities of color and law enforcement exposed longstanding economic frustrations. Addressing the employment challenges faced by both types of communities will take serious, long-term commitment and public policy focus untethered from the news cycle.

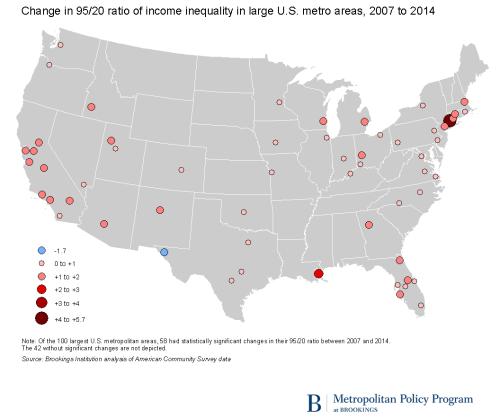

Second, while jobs are certainly a shared priority for cities and rural areas, their divergent trend lines in employment opportunity merit reflection. The past 10–15 years have strengthened the economic hand of many cities, as coming-of-age generations seek a more urban lifestyle, and as an increasingly services-focused U.S. economy concentrates in places with greater access to highly skilled labor, innovative institutions, and strong global connectivity. These dynamics, in turn, have raised demand for workers in such places, even for those with lower levels of formal skills, drawing them into jobs at increased rates.

Those same dynamics have simultaneously disadvantaged many small towns and rural areas. If what economists call “agglomeration” is increasingly the route to employment opportunity, can small places succeed? As my colleague Mark Muro has argued convincingly, manufacturing jobs aren’t coming back to those communities to a degree anywhere close to the number that have departed. Part of the answer may lie in strengthening connections between larger and smaller places through infrastructure investment and shared economic development strategies. Such efforts could unite economic leaders in cities and their surrounding rural areas in older industrial states, if state lawmakers choose not to pit those interests against one another. Yet if recent trends hold, efforts to bring jobs back to small-town America seem likely to face an uphill battle against market forces that have put jobs further out of reach for many of their residents.

-

Footnotes

- My colleague Chad Shearer used a version of this classification system in a recent post-election analysis; this analysis updates and extends that system.

- Five-year estimates from the American Community Survey provide the only statistically reliable labor market data for the thousands of U.S. counties with populations under 20,000.