Despite increased evidence of economic recovery, real wage gains have been niggling over the past decade and have given rise to growing claims of unfairness. I agree that all of the evidence points to uncommonly small gains in workers’ real (adjusted for inflation) wages, but it is instructive to understand the reasons for the poor performance. We can trace the change in real wages to three primary determinants of: (1) gains in labor productivity, (2) the division of earned income between labor and capital (profits), and (3) the allocation of labor compensation among wages and nonwage benefits.

Most importantly, the growth in the average real wage is largely determined by improvements in labor productivity, output per worker hour. Without such gains, an increase in the average nominal wage will simply be passed forward in the form of higher prices, and higher real wages for some can only come at the expenses of lower wages for others–a zero-sum game. However, the growth in the real wage can deviate from that of productivity due to changes in labor’s share of total income. Historically, labor’s share has been one of the great long-run constants of economics, but its surprising decline in recent years has stimulated renewed interest in its determinants, and a popular book by the French economist, Thomas Piketty, put the issue at the center of the debate over the sources of growing income inequality. Third, workers often focus on their take-home or money wage, ignoring the magnitude of benefits (primarily provisions for retirement and health insurance) that are paid for through their employer.

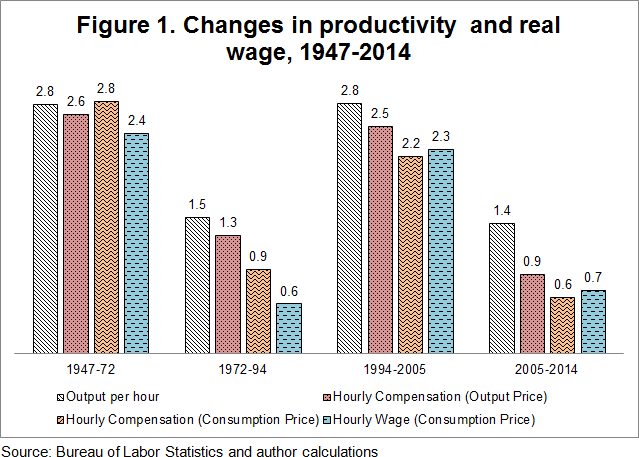

The relevance of these three determinants of real wages can be illustrated by focusing on government statistics covering workers in the private nonfarm business sector for which we have reasonable measures of productivity and wage payments. Public-sector workers are largely excluded because of problems in measuring output and productivity in a nonmarket context. Figure 1 summarized the linkages between productivity growth and real wages over the entire post-World War era. The immediate post-war years up to the mid-1970s encompassed a span of extraordinary productivity improvement as major innovations, accumulated during the years of economic depression and war, were applied on a widespread basis. Growth slowed in the 1970s and 80s for reasons that economists have never fully understood, but productivity surged again in the late 1990s and early 2000s under the impetus of major innovations in information and communication technologies (ICT).

Those episodes are clearly evident in the cycle of productivity growth shown in figure 1, which averaged 2.8 percent per year for a quarter of a century before slowing to 1.5 percent in 1972-94,and rose back to 2.8 percent in the boom years of 1994-2005. Unfortunately, the last ten years looks like a return to the low-growth performance of the 70s and 80s. However, the severity of the last recession greatly complicates the interpretation of the causes and permanence of the slowdown; significant economic studies have emerged on both sides of the debate. All the same, its importance for gains in real wages and living standards is evident in the falloff in productivity growth to half its prior pace.

Absent a change in labor’s share of the income generated from production, real wages should rise in lockstep with labor productivity, Labor’s share within the nonfarm sector has been slowly declining since the end of the war, but for most of the period that was entirely due to an adjustment to the data to include the labor-type income of the self-employed.[1] There is however, a larger and more evident decline in labor’s share since 2000.

It is also important to compare productivity and real wages using comparable price indexes. Productivity is an output concept and an output-price deflator should be used to equate output and the real cost of labor. However, workers are more interested in what their earnings can buy, and it is equally useful to deflate nominal wages values with a measure of consumption prices. Those two price measures are not the same because the mix of products that Americans produce is not the same as what they consume.

In figure 1, real wages are shown on the basis of both output and consumption prices. The basic stability of labor’s share up to 2000 is evident in the minor difference between the growth in labor productivity and real wages (output prices), but the increase in real wages falls short of that of productivity by a substantial ½ percent annual in the 2005-14 period. In addition, workers have suffered a consistent loss in their terms-of-trade (output prices/consumption prices since the mid 1970s), further eroding their real incomes.

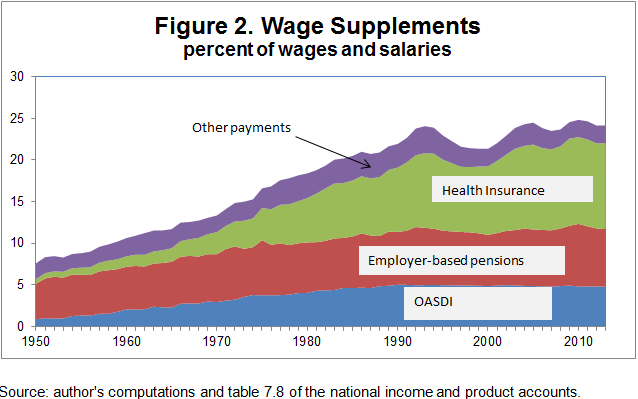

Finally, there has been an enormous expansion of the employment-based system used to finance the provision of retirement and health care (supplements). Those costs are often not evident to the typical worker, even though the benefits are popular. However, the costs have played a surprisingly minor role in the distinction between labor compensation and wages in recent years. In fact, the growth of take-home pay in nonfarm business, shown in figure 1, has slightly outpaced that of hourly compensation since 1995. The evolution of the non-wage benefits can be seen more clearly in figure 2, which displays the cost of the major programs and a percentage of wage and salary payments. There has been no major expansion of the basic social security program since mid-1980s, and employers are phasing out their contributions to defined benefit plans in favor of defined contribution plans that are more reliant on direct employee contributions. The big expansion has been in employment-based health insurance, but even those costs have slowed in recent years. The category of other payments includes workers’ compensation and unemployment insurance.

There are other measures of real wage changes that imply even smaller gains in real wages. Most prominently the employment cost index (ECI) is widely used as a measure of nominal wage changes. It excludes the effects of changing in the composition of jobs, which makes it ideal for measuring inflation pressures, but is not fully comparable with the productivity measures that include changes in the composition of output and employment. The ECI also does not include stock options and other forms of compensation to workers at the top of the wage distribution. Household base surveys also provide estimates of wage changes but exclude the costs of most supplements. Both the ECI and the household survey indicate even lower rates of real wage growth, but they are less comprehensive in their coverage than the national accounts. While no full reconciliation is available, the most important differences are believed to be concentrated in the reporting of wage data for workers are the very top of the earnings distribution.

Still, the data of figure 1 clearly document a major slowdown in real wage growth. It is largely the product of poor productivity performance over the past decade, but that may not be surprising in view of the enormous economic losses that were precipitated by the financial crises. Nor is it unprecedented if the ICT revolution is viewed as a transitory phenomenon. The new phenomenon is the decline in labor’s share of income for which we have no satisfactory explanation. It may reflect the huge rents that accrued to commodity producers during the boom of the last decade, and as that comes to an end labor’s share may rise toward the historical norm. However, some analysts point to the development of a highly competitive global market for labor combined with a more general reduction in product-market competition through reliance of mergers, IT patents, and regulations that suggest a reduced labor share may be a longer-lasting phenomenon.

[1] The income of the self-employed reflects a return on their invested capital as well as their own labor hours. The Bureau of Labor Statistics imputes a wage rate equal to that of employees in their industry. Over the post-war era, the share of the self-employed in the workforce has slowly declined.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edSources of Real Wage Stagnation

December 22, 2014