And just like that, federal infrastructure policy is back in the news.

Democratic Party leadership were all smiles after a White House meeting yesterday to discuss future infrastructure policy. President Trump appeared to agree to their high-level terms: $2 trillion in new federal spending that would cover transportation, water, broadband, and energy grid investments. President Trump even pledged the administration would take responsibility—three weeks from now—to present ideas for new funding sources.

But crafting and passing major infrastructure legislation has been challenging for a reason, and there’s little reason to believe this time will be different. I see three distinct challenges that could quickly turn optimism into disillusionment.

Problem 1: The money

A $2 trillion, 10-year infrastructure spending package is an enormous sum of money. Back in 2017 we studied historic federal infrastructure spending all the way back to the 1930s. As the chart below shows, if the federal government spends $200 billion more per year on infrastructure, that would rival spending levels not seen since the scale-up of the Clean Water and Safe Drinking Water Acts in the 1970s and early 1980s.

Where would the feds find $200 billion in new annual revenue? Re-upping the surface transportation law with a gas tax increase could do some of the work, and Capitol Hill legislators could even get cute and count reauthorization of current surface transportation law as new money (something Eno Center for Transportation expert Jeff Davis suggested could happen). The issue is that federal law prohibits gas tax revenues from funding anything but certain surface transportation projects, and certainly not water and broadband investments. Moreover, it’s politically treacherous to sell major gas tax increases to the public.

That means we’re talking about some mix of higher individual or corporate income tax rates, gas tax hikes, new telecommunications taxes, and outright borrowing to get to $200 billion. Securing that kind of revenue will take a level of trust between the two political parties we haven’t seen in some time.

We’re talking about some mix of higher individual or corporate income tax rates, gas tax hikes, new telecommunications taxes, and outright borrowing to get to $200 billion (in new annual revenue).

Nor are early GOP reactions positive. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has already rejected the idea of rolling back parts of the 2017 tax cut. White House Chief of Staff and Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney cast further doubt on any deal absent major permitting reform.

Problem 2: The timing

In times of economic and fiscal crisis, higher federal spending can help stimulate the macroeconomy without inducing inflation and crowding out private capital. Right now, however, the U.S. labor market is at or near full employment. Financial markets are relatively stable.

So pumping an extra $200 billion per year into infrastructure spending runs a real risk of crowding out private investment and increasing costs for projects (since government contracts will need to pay more to attract workers). It’s also likely to discourage state and local spending, which means the net fiscal effect of a $2 trillion federal package could fall well short of that level.

And then there’s the politics. With unemployment low and financial stability strong, will congressional legislators be in the mood to make a deal?

Problem 3: The programming

This is the area that worries me the most, but it’s talked about much less. The focus on the dollar figures obscures a more significant and challenging question: what exactly are we spending all this money on?

Federal infrastructure legislation is woefully outdated and is due for a refresh, but it won’t be easy.

- The surface transportation program continues to allow states to spend money relatively carte blanche, leading to high-speed roadway projects that incentivize sprawl, lock households regardless of income into car ownership, and intensify transportation pollution. Is that how we want to spend new money?

- The federal water program sends effectively no money directly to regional water utilities, which is why it’s hard to have a federal response to crises like that in Flint, Mich. How exactly will Congress and the EPA build a new water grant program, and how will they determine what kinds of projects will qualify and which utilities deserve the most proportional investment?

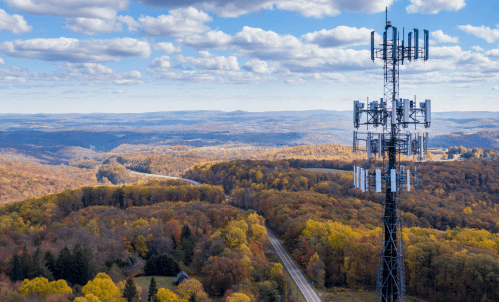

- The private sector builds and operates the vast majority of the country’s broadband infrastructure. Meanwhile, federal broadband programs are often criticized for either investing inefficiently in rural America or fraud within pricing support programs. Is Congress ready for a robust broadband program that will gather support on both sides of the aisle?

This list barely touches on all the structural concerns legislators will need to address under each of the three infrastructure sectors, but it’s meant to indicate the kind of policy fights that will happen once multiple congressional committees start crafting any legislation. Put simply: the country is in for a slog of a negotiation even if the two sides agree on funding sources.

Infrastructure reform is on an electoral clock

Not only are these three problem areas difficult to overcome on their own, time is of the essence. If Congress can’t craft a policy and funding package by the end of this coming summer, then the 2020 electoral clock will be hard to ignore. Presidential primaries will be in full swing and party leaders may be unwilling to make a deal.

It’s great to see the two parties find some common ground around infrastructure, and to do so within the West Wing no less. But we should all be skeptical whether the good news can last.

Commentary

What to make of the White House infrastructure meeting?

May 1, 2019