Many analysts have suggested the midterm elections were more about cultural hostilities than anything else. And there’s no doubt the nation is dangerously fractured across lines of race and religion.

And yet, it’s worth noting that last week’s vote reaffirmed that America’s stark and massive economic divides—which align with and inform those cultural fractures—are alive and well.

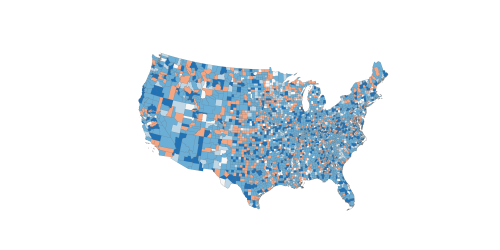

To better understand these economic divides, we worked with John Harwood at CNBC to update an analysis we conducted after the 2016 presidential election by linking congressional vote outcomes for all called races—seven are still uncalled—with standard county economic data to assess local economic differences. Sure enough, the numbers again reveal extremely sharp differences in the voting behavior of what are, in effect, two different economic nations within America.

Looking at congressional districts, the analysis shows that the governing majority of 228 congressional districts (as of this post’s publish date) won by the Democrats last week encompasses fully 60.9 percent of the nation’s economic activity as measured by total economic output in 2016. Democratic districts are more productive, with a strong orientation to the advanced industries that inordinately determine prosperity. Notably, voters in these districts possess bachelor’s degrees at relatively high levels and work disproportionately in digital industries like software publishing and computer systems design.

By contrast, the 200 seats (as of this post’s publish date) captured by Republicans represent a much different swath of the economy. While almost as numerous as Democratic holdings, these seats represent just 37.6 percent of the nation’s output, reflecting a productivity level of just $106,832 per worker, and appear much more oriented to lower-output industries as well as non-advanced manufacturing (e.g., apparel, food, paper). Relatively fewer adults in these districts possess a bachelor’s degrees and fewer work in digital services.

The upshot of these contrasting caucus profiles is unmistakable: The sharp political divide that surfaced in 2016 between the densest, most productive and future-oriented portions of the economy and the rest of it—between what Jim Tankersley of the New York Times has called “high-output” and “low-output” America—remains a revealing, disconcerting fact of modern economic and political life.

As of the midterms, there are now two divides. One divide will continue to play out in the next two years in the House; with a Democratic majority that factually represents 60 percent of the economy, with its most productive districts and industries containing high shares of workers with college degrees. In this chamber a modest urban and suburban majority should be able to prevail in narrow votes articulating key agenda points relevant to high-output America.

However, the other divide—the one in the Senate now exacerbated by the Republicans’ net gain of between one and three seats—looms much more consequentially. With new GOP gains in the chamber, 21, mostly rural, low-output—ranging from Arkansas to Wyoming—now host two Republican senators and are poised to serve as an even more reactionary veto on the projects and priorities of the high-output America. These 21 states will easily be able to outvote the 19 states with two Democratic senators, even though the Republican 21-state caucus represents just 30.3 percent of the nation’s output.

The midterms have in fact ratcheted up an economic, as well as social, stalemate in the nation. Even more now, a rurally oriented Senate majority representing “traditional” agricultural, energy, and production economies stands ready to block efforts to address the needs of an urban and suburban “knowledge” economy. That latter economy is more oriented to future-learning digital services, and thus depends on solutions to major issues like R&D funding, worker reskilling for a digital age, immigration, health care, income inequality, and international cooperation. In that sense, what journalist Ron Brownstein calls the “prosperity paradox” remains as true as ever. Even as economic growth is concentrating in thriving urban and suburban communities, Republicans rooted in non-urban places remote from those future-leaning ecosystems continue to wield disproportionate power in Washington.

That’s a problem, as Brownstein wrote last week: The two parties even more this fall represent “what America has been and what it is becoming”—and they are at a standoff. Going forward, the question is whether a nation that fails to support the needs of its core, high-value economy can truly thrive.

Commentary

America’s two economies remain far apart

November 16, 2018