After decades of authoritarianism and rule by a military junta, Myanmar (also known as Burma) has entered a historic new phase in its political development. The pro-democracy National League for Democracy (NLD)—led by Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung Sang Suu Kyi—overwhelmingly won the November 8 national election, defeating a political party representing the military and affiliated crony capitalists.

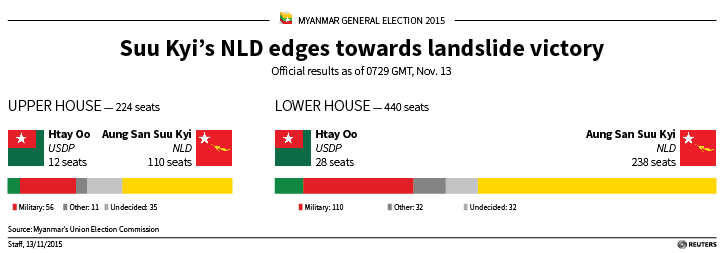

In the new parliament to be formed in 2016, the NLD will occupy 387 of the 664 seats in the two houses, while the pro-military Union Solidarity Development Party (USDP) will retain only 42 seats out of the 360 it now holds. Another 166 seats are reserved for the military.

Official results of the 2015 Myanmar general election as of November 13. Credit: Reuters.

In contrast to the 1990 election, the military and the quasi-civilian regime (created in 2011 when Myanmar embarked on democratization) are actually expected to cede power this time. Although a pro-junta legislative clause in the constitution bars Suu Kyi from becoming president of the country, she has already declared herself “above the president.” It is not yet clear what her formal title and post will be.

The change in governance ushers in a new phase in the peace process with ethnic separatist groups that have been at war with the Burmese government for decades. For the new government, a core part of that challenge will be the many illegal economies that have been intertwined in both the conflict and the peace processes for decades: drugs, timber, wildlife, and gems.

A long and troubled history

Myanmar’s policies toward drugs and other illegal or problematic extractive economies have been in the eye of the international community—and indeed, in the eye of an international storm—for a long time. For decades, Myanmar has been an epicenter of opiate and methamphetamine production. Poppy cultivation and opium production have coincided with five decades of complex and fragmented civil war and counterinsurgency policies. Waves of poppy eradication in the 1970s and 1980s motivated by both external pressures to reduce illicit crops and internal desires to defund the insurgencies failed to do either.

An early 1990s laissez-faire policy of allowing the insurgencies in designated semi-autonomous regions to trade any products—including drugs, timber, jade, and wildlife—and also the incorporation of key drug traffickers and theirs assets into the state structures helped reduce conflict. The Burmese junta negotiated ceasefires with the insurgencies and underpinned the agreements with giving the insurgent groups economic stakes in resource exploitation and illegal economies.

Under pressure, including from China, opium poppy cultivation was suppressed in the late 1990s and early 2000s, even as unregulated and often illegal trade in timber, jade, and wildlife continued. Although local populations suffered severe economic deprivation, the ceasefires lasted. Since the middle of the 2000s, however, the ceasefires have started breaking down, and violent conflict has escalated.

There are multiple reasons for this escalation and for the difficulties of transforming the ceasefires into a lasting, just, and inclusive peace. One of them is the current efforts of the government and military of Myanmar, as well as powerful Baman and Chinese businessmen and powerbrokers, to restructure the 1990s economic underpinnings of the ceasefires to increase their own profits.

The old-school way

Although the military of Myanmar will not give up its influence on the peace processes or control over the ongoing and intensified fighting in large parts of the country, Suu Kyi and the NLD will become far more involved in the negotiations and decisionmaking. They draw important support from the contested ethnic areas that participated in the elections.

The conventional view holds that illegal drugs, as well as other resources such as timber or wildlife, fuel violent conflict. Militant groups that penetrate the drug trade and other illegal economies often derive large financial profits from it and grow powerful. Hence, it is often argued that in order to defeat the insurgents, it is necessary to take away their money by suppressing the illegal economy by, say, eradicating the poppy fields.

This view is wrong. Not only does the siren song of eradication rarely produce the promised suppression of financial flows to belligerents—as both they and the illicit crop farmers find ways to adapt—but it is counterproductive. It alienates rural populations from the government and thrusts them into the hands of the insurgents. Winning the military conflict or negotiating peace often requires that suppression actions against labor-intensive illicit economies stop. Tacitly or explicitly permitting the illicit economies, as much as external actors may condemn it, is often crucial for winning hearts and minds and ending conflict. It may also be crucial for giving belligerent groups a stake in peace.

In Myanmar, many of the conventional policy prescriptions will likely be counterproductive for achieving peace. At the same time, a (narco-) peace that returns to the economic deals of the 1990s will further exacerbate the environmental destruction that Myanmar has been experiencing over the past three decades. The peace will turn into plunder.

Development-based policies toward reducing illicit drug production are crucial.

Even as Suu Kyi and the NLD will have to calibrate their relationships with Myanmar’s key trading partners and donors—such as China, Thailand, and the United States—they should not just swallow the counterproductive conventional wisdom about how to deal with the nexus of conflict and illegality. Instead, they—as well as the outside partners and donors—would do well to learn from the policy outcomes of Myanmar’s own history, as well as the successes and failures of its neighbor Thailand. Through determined commitment over 40 years, comprehensive rural development, and auspicious overall economic conditions, Thailand has been the most successful country ever to eliminate illicit crop cultivation on a countrywide level. However, since 2001, its policies toward drug users amount to an inhumane and counterproductive “war on drugs.” Myanmar’s history and Thailand’s, therefore, both run counter to the conventional wisdom.

Outside the box

Both Myanmar’s ethnic fighting and its narcopeace have come at great cost, including extensive drug production and unrestrained environmental destruction. Development-based policies toward reducing illicit drug production are crucial for avoiding such costs while maximizing the chance for peace and social justice. They must equally focus on preventing the emergence of unrestrained logging and wildlife trafficking (and other environmentally-destructive replacement economies) as on reducing methamphetamine and heroin production.

Commentary

Peace or plunder? Illegal economies in Myanmar’s ethnic conflict

December 7, 2015