The world has changed dramatically over the last 10 months. In the midst of such broad changes, we might be tempted to throw away our old ways of doing things and figure out a new approach to meeting the needs of women and girls around the world.

But with regard to gender equality in education, many of the fundamentals have stayed the same, and our challenge is to figure out how to update our work to this new reality, while not forgetting the commitments and goals—and other challenges—that preceded COVID-19.

This spring, the Population Council’s GIRL Center launched the Evidence for Gender and Education Resource (EGER), a searchable, easy-to-use, interactive database to drive better education results for girls, boys, and communities around the world. It includes information on current practice (who is doing what, where?), current evidence (what has worked in some settings?) and current needs (where do challenges remain?) in global girls’ education. Based on insights from EGER, we will be launching a 2021 Roadmap for Girls’ Education in the coming months.

What knowledge did we bring into this crisis?

As we think about goals for 2021 and beyond, it can be helpful to clarify the fundamentals of our work that remain true. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, there was enormous progress in expanding access to school, and in achieving gender equality in education globally. But in many places gender gaps remained and progress in attainment had stagnated. Although the percentage of those out of school had declined, before COVID-19, more young people, especially girls, were out of school in low-income countries than ever before. Even when they were in school, girls and boys were often unable to gain basic skills, resulting in a global learning crisis. Our recent research shows that young people, especially girls, were also losing the skills they gained in school after leaving, especially when they were unable to apply those skills in the outside world.

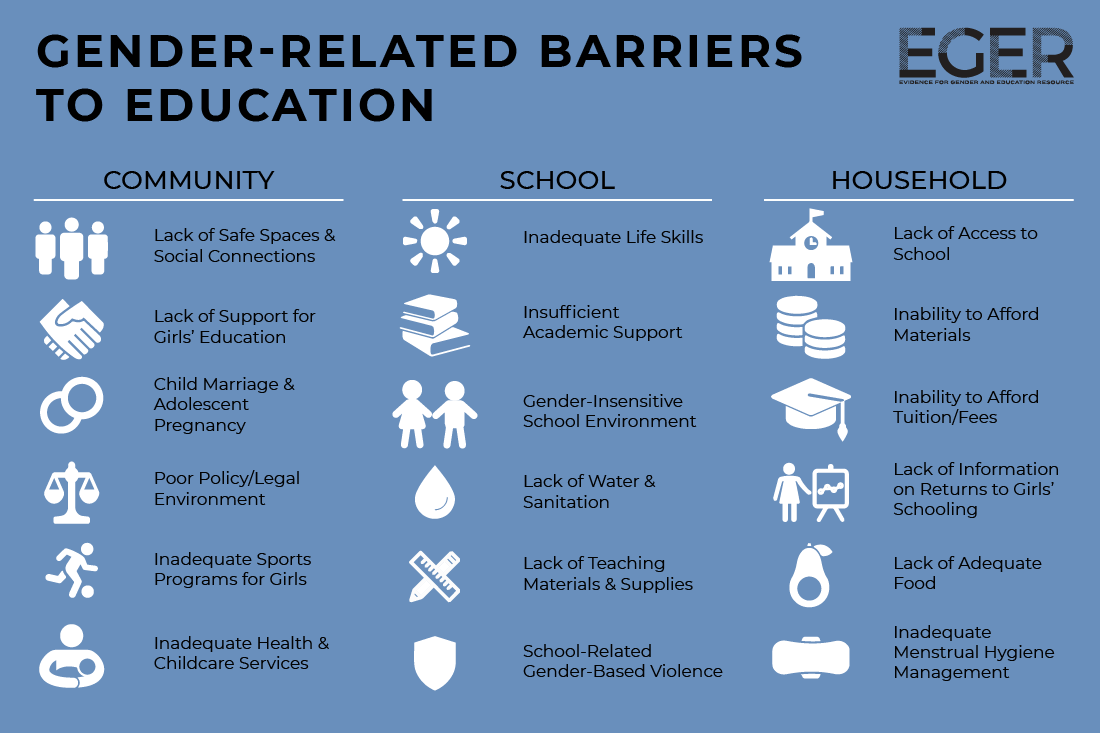

Before COVID-19 we were also seeing important—and persistent—gender-related barriers to school in many countries. To inform EGER, we conducted a systematic review of the evidence on what works to address gender-related barriers to schooling, and we developed a framework of perceived barriers. It shows gender-related barriers to education for girls at the community, school, and household levels. Underlying these barriers are two powerful forces: social norms and poverty.

Barriers at the school level are familiar—gender-insensitive school environments, lack of teaching materials and supplies, and school violence. But also important are barriers at the community and household levels, including child marriage, school access, and financial constraints.

While the full educational repercussions of COVID-19 have not yet unfolded, the pandemic is layering unprecedented pressures on top of existing challenges. But an important question for us to consider is this: In what ways have these barriers fundamentally changed due to COVID-19? And in what ways has COVID-19 simply exacerbated existing barriers?

What, if anything, has fundamentally changed in our work?

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the Population Council team in Kenya has partnered with the Executive Office of the President’s Policy and Strategy Unit to interview nearly 4,000 adolescent girls and boys by phone in four locations: Kisumu, Wajir, Kilifi, and the informal settlements in Nairobi.

For context—at least based on available data—after a peak in new cases in Kenya in November, new cases of COVID-19 are now declining, with about 200 per day at the end of December. So now the focus is on indirect effects of the pandemic—the effects of school closures, increasing economic strain, and challenges in accessing health care.

Connecting these two pieces of work—our current understanding of gender-related barriers to school, and a snapshot of what’s happening now in Kenya— how does COVID-19 change what we know?

1. Economic distress. Evidence from before COVID-19 tells us that addressing financial barriers to school can be effective not only to get young people into school, but potentially to close gender gaps, as well. Undoubtedly this remains true, even as the severity of economic barriers changes.

In Kenya, while most young people say they plan to go back to school upon reopening in January, we also see indicators of severe economic distress and a fear that inability to meet the costs of education will prevent reenrollment. For example, the majority of young people in three of the four settings in our study reported experiencing increased food insecurity due to COVID-19. This type of economic insecurity may well play out in terms of school access in the coming months and years.

2. Challenges in accessing education. We also know that expanding access to school—especially in settings where access is still a challenge—can be a very effective way to increase enrollment and close gender gaps. For example, school construction programs in countries like Burkina Faso or buying bicycles for girls in India, have been effective. But what does “access” mean now? How has that changed?

In Kenya, the majority of adolescents say they are doing some kind of schoolwork or learning at home during the pandemic, with the exception of Wajir, where fewer than 20 percent of 10- to 14-year-old girls, compared to 30 percent of 10- to 14-year-old boys indicated this was the case. When asked why they were not doing schoolwork at home, the most common reasons were that the school hasn’t provided lessons, and/or they needed to help with chores at home.

3. Importance of pedagogy. We have also seen over and over again that improving pedagogy, such as helping teachers adapt the curriculum to students’ different learning levels, is effective. What does this look like during and post-COVID-19? What models can we build on? (Hint: There are promising models out there already!)

In places like Wajir, where many young people have spent nearly a year without doing schoolwork or reading at home, ensuring school access is only the first step. Teachers will be faced with new challenges in helping students catch up and get back on track, with perhaps a broader range of skills in their classrooms than ever before.

Although it has been 10 months since the COVID-19 pandemic began, we’re only starting to see its effects—both direct and indirect—on school-age children and their families. As we think about what comes next, let’s not forget the fundamentals—what we already know about gender-related barriers to schooling, and what has worked to improve education for girls before. What we need to understand is how COVID-19 changes those fundamentals, and how we must change our plans in response.

Commentary

Remember the fundamentals as we build back better in girls’ education

January 12, 2021