The COVID-19 pandemic has forced us to fundamentally rethink the design, implementation, and measurement of our Girls’ Education Program (GEP) at Room to Read to ensure girls are supported, continue their education, and develop the life skills they need for long-term success (see our theory of change graphic below).

As the pandemic took full force in the first quarter of 2020 and schools closed across the eight countries where we implement our program, our typical way of working was rendered obsolete—nearly overnight. We recognized the long-term negative effect that school closures can have on girls’ life outcomes in low-income communities based on evidence from the Ebola outbreak in West Africa and many other crises and conflicts. We also recognized that as families deal with unprecedented levels of stress associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, the risk of intrafamily conflict and gender-based violence increases, negatively impacting girls’ self-confidence, well-being, and ability to effectively navigate key life decisions.

To counter these challenges, we harnessed the power of a team of community-based staff who knew the local context, were close to the realities and needs of the girls, and were highly invested in their success. These strengths drove our immediate response to school closures, transitioning our school-based small group life skills and mentoring sessions into a system of remote one-on-one mentoring sessions within a matter of weeks. Our teams’ knowledge of program participants and their families facilitated this quick response and focused our mentoring on four priority areas: well-being, academics at home, staying safe and healthy, and girls’ return to school. Over the ensuing weeks, we worked at a global level to assess the best practices used across countries and brought those practices together into a common set of guidance, which is still evolving.

In some countries where connectivity is greater and data is cheaper, social mobilizers are also leading virtual group mentoring sessions, ensuring that girls continue to have access to the support of their peers, which is crucial in times of stress. In other countries, such as Nepal and Bangladesh, we have developed and broadcast radio programs with life skills and mentoring content.

Rapid transformation of research, monitoring, and evaluation

In line with our programming changes, we also had to fundamentally rethink our approach to research, monitoring, and evaluation (RM&E). Our existing strategies and processes to track, measure, and learn from our programs were not applicable, so we quickly designed a new RM&E framework, with a focus on efficiency and timeliness. In the initial phase of our COVID-19 response RM&E work, we took a real-time approach to gathering and analyzing context and implementation data—diagnosing and adapting in short cycles. This has informed our immediate operations, provided a basis for evolving the design of our programs, and supported discussions with governments and partners. We could pivot quickly because of the long-term trusting relationships our field staff have with school leadership, teachers, parents, students, and government institutions and the strong preexisting data systems we had in place. Despite considerable constraints on mobility and connectivity, we have managed to gather reliable data on the reach of our pivot activities, including, for example, the number of mentoring sessions (Figure 1) and the proportion of girls in our program receiving mentoring (Figure 2).

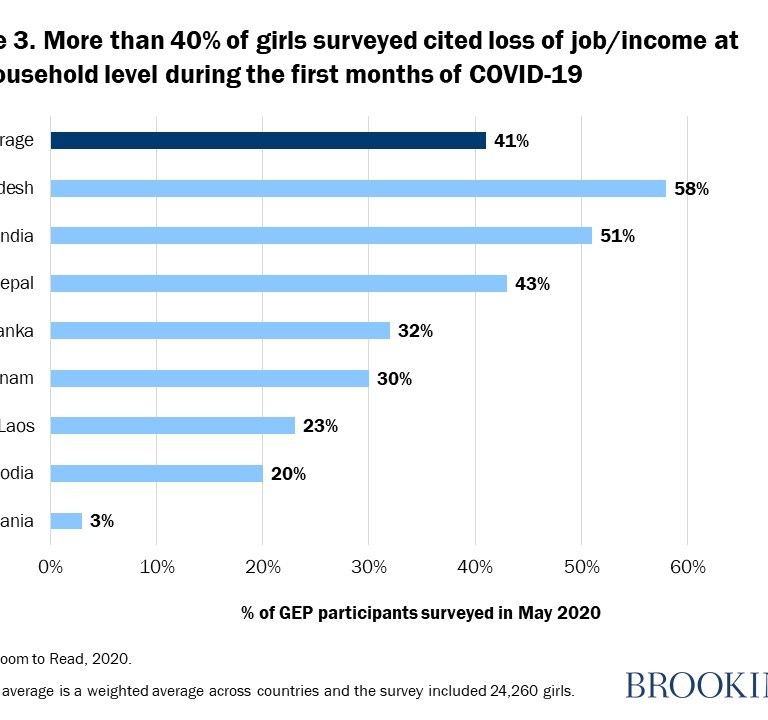

We are also collecting critical information about the risks that the girls in the program are experiencing during school closures and integrating a brief risk survey into the individual remote mentoring sessions; social mobilizers, who deliver the mentoring sessions, complete a quick survey on their phone to record survey responses. Referencing the evidence base and our historical data, we focused on three risk factors: whether girls were keeping up with their studies during school closures, whether anyone in their household had lost a job or income because of the pandemic, and whether they were concerned about their ability to return to school once open again. Early in the pandemic, our data showed incredibly high levels of risk, with nearly 50 percent of girls surveyed citing at least one risk factor. The most prevalent factor cited was the loss of a job or income, with an average of 41 percent of the 24,260 girls surveyed in May 2020 across eight countries (Figure 3). These data have allowed us to tailor our programming at the individual and country levels during the crisis. Over the course of the pandemic, we have continued to collect risk data and have seen a decline in the reported prevalence of lost jobs or income in the household due to the pandemic, but fairly steady (albeit much lower) reported risk factors for the other two categories as shown in Figure 4.

Over the course of the pandemic, we have continued to collect risk data and have seen a decline in the reported prevalence of lost jobs or income in the household due to the pandemic, but fairly steady (albeit much lower) reported risk factors for the other two categories as shown in Figure 4.

Looking forward

We continue to adapt our programming and RM&E systems as the situation across countries becomes more complex—with some school systems opening (Cambodia, Laos, and Tanzania), others opening and then closing (Sri Lanka), and still others remaining entirely closed (Bangladesh, India, and Nepal). A focus on innovation, speed, and flexibility will be key. We recognize that education delivery as we have known it is an article of the past. Even when school systems reopen and countries emerge from the pandemic, there will be critical opportunities to learn from this crisis, integrate our innovations into our longer-term strategies and reenvision how we can most effectively support girls, their families, and the education systems that serve them.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Reimagining girls’ education during COVID-19: Lessons from adapting programs and measures

January 7, 2021