In a 2017 discussion with the president of Echidna Giving, I was asked a simple but destabilizing question: “Tell me about the innovation in the girls’ education project you are coordinating in Northern Nigeria?” This was a difficult question given that innovation is a much used but seldom defined term among girls’ education actors.

In the girls’ education space, innovation means different things to different actors. For Partnership to Strengthen Innovation and Practice in Secondary Education (PSIPSE), innovation is a key assessment for grant making. For others it is associated with technological applications and sustainability. The Center for Universal Education (CUE) defines the concept as “any tools, policies, programs, or ideas that break from previous practice.”

I have since reflected on two different initiatives I shared with the Echidna Giving president. In the first, when my colleagues and I at the development Research and Projects Center (dRPC)—a Nigerian NGO that I founded—implemented the PSIPSE project, we aimed to increase learning outcomes and expand income opportunities for the girls. The project blended vocational skills acquisition in after-school clubs with teacher training in girls’ senior secondary schools in two educationally disadvantaged states (Kano and Jigawa) in Nigeria. Between 2013 and 2017, PSIPSE indeed improved learning outcomes with an 80 percent increase in students graduating with senior secondary certificates in all five subjects Additionally, 50 percent of all girls in senior secondary school class 3 completed vocational skills programs in after-school clubs.

However, only a third of the girls who graduated from PSIPSE secondary schools in 2017 and 2018 with five credits and who had also completed the vocational skills program actually transitioned to tertiary education. None of these girls used their vocational skills to start their own businesses. The other two-thirds of girls who graduated with five credits and received vocational training either got married or reported that they were staying at home “waiting for God to decide” their futures. What explains these findings? Among the reasons explored further in a recent CUE report are household poverty, community preference for early marriages, inadequate information on tertiary education pathways, and the perception that government youth enterprise programs are inaccessible without political connections.

The second initiative focused on 750 girls from the poorest Nigerian households, with the lowest learning outcomes and who graduated in 2017 with one or no subject certificates and only completed some modules of the vocational skills program. Their desperate and vulnerable situation called for a customized spin-off intervention. Despite their low learning outcomes, with the support of the Kano and Jigawa state governments we began helping 40 of these girls start up culturally acceptable business enterprises within their local communities. The girls were trained to be teachers of children ages 3 to 6 years in early childhood development (ECD) centers located in the foyer of their family homes. While this was a promising initiative in 2017, I was not convinced that it could be considered an “innovation” since these girls had technically “failed” our initial intervention.

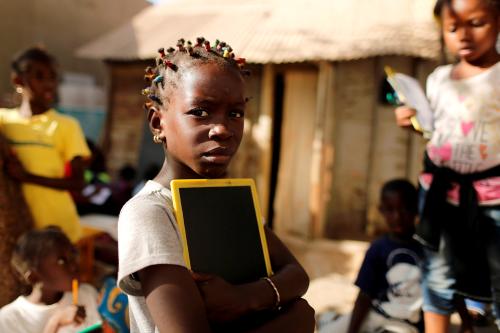

By project close, though, many viewed the “failed” girls running home-based ECD centers as the “real” innovation of the project. By December 2019, 39 of the 40 girls were each managing ECD schools with an average of 55 children, most of whom were unlikely to attend school other than Koranic education. Moreover, 35 percent of all of the ECD centers’ pupils were little girls. For poor parents and guardians, the school fee of $4 per child per month was much more attractive than the going rate of $27 per month at private ECD schools. And as of February 2020, all of the girls remain unmarried, more than half expressed a desire to re-take their secondary school exams, and 10 wanted to enroll in part-time professional teacher development programs. In addition, many of the girls were receiving support from local government authorities and male community leaders to maintain their ECD centers—only one closed her school due to a chronic illness.

When forced to close schools in March 2020 to stem the spread of COVID-19 in Nigeria, the 39 girls still running their ECD centers quickly repurposed their home school spaces and entrepreneurial skills to generate new sources of income. This included giving community lectures on social distancing; selling airtime recharge cards to community members with mobile phones, as well as locally made disinfectants; and renting out school toys. While COVID-19 meant that income has fallen for these girls, enthusiasm had not waned as they look forward to school reopening in July 2020.

Upon reflection, what have these two PSIPSE Nigeria initiatives taught us about innovation in girls’ education? We learned that innovation can emerge from unexpected initiatives: through experimentation, problem-solving, and by recognizing challenges and retooling strategies so that those who may have “failed” can still achieve some measure of success. In this way, innovation is about building sustainability and resilience within the least likely to succeed and the most vulnerable populations. It is also about recognizing limits and imagining hanging fruit on fledgling trees. But perhaps most importantly, innovation is not a thing but an ever-evolving dynamic process of adaptation.

Photo credit: dRPC, Kano December 2019

Commentary

Reflections on innovation in girls’ education in Nigeria

June 26, 2020