This blog highlights lessons from of a recent conference of education officials from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, hosted in partnership between the Center for Universal Education and the Education for Competitiveness initiative at the World Bank at the Center for Mediterranean Integration in Marseilles, France.

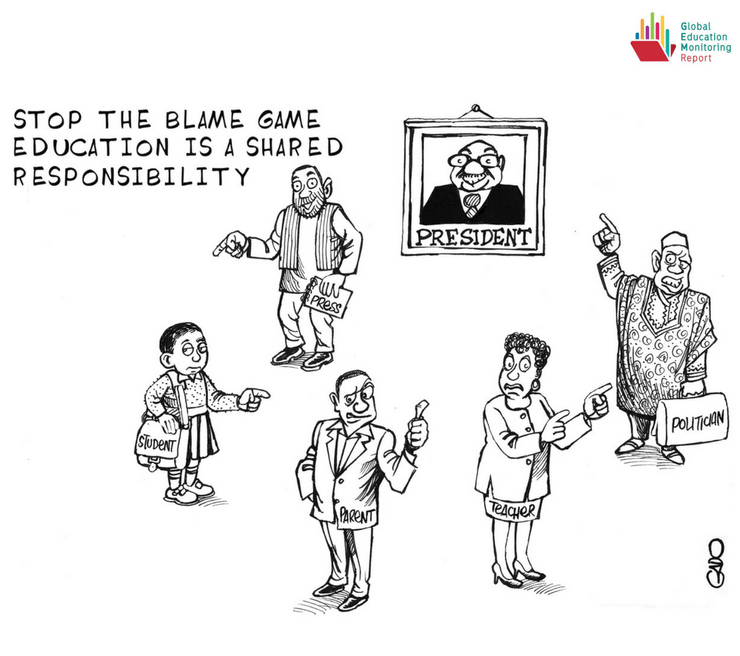

This message is loud and clear in two flagship reports on global education, both released this month: the Global Education Monitoring Report, the U.N. Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) annual snapshot of progress toward achieving the Sustainable Development Goal on Education (SDG4), and the World Bank’s 2018 World Development Report, the first in the series to focus on education since its start in 1978.

What, then, is a country supposed to do when looking to improve student learning when there is no tried-and-true prescription for what an education system needs to look like? When simply replicating “best practices” is not enough to ensure that all children are learning? When what is effective in improving learning in some contexts may not work in others, or may even be detrimental?

The answer is that decisionmakers need access to and capacity to use consistent, high-quality data on how the system is performing, evidence on what affects student learning in their context, and the motivation to work toward the ultimate goal of equipping all children with the skills they need to succeed in their lives.

This intersection between information and accountability was the theme of a recent conference of education officials from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Participants from Algeria, Jordan, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Palestine gathered to share innovative monitoring and data collection processes, and discuss strategies to enhance accountability among educational actors: the state, schools, and citizens.

Schools in Jordan, for example, are visited regularly by teams of assessors from the recently established Education Quality and Accountability Unit, an independent unit within the Ministry of Education, to check progress toward standardized national quality indicators. Assessors are highly experienced teachers, principals, and advisors that receive 18 months of intensive training to evaluate school development plans, observe teachers and classrooms, interview students and parents, review student achievement, and make clear recommendations for action based on a mix of quantitative and qualitative indicators.

Similarly, Palestine has introduced results-based management processes that employ program managers to monitor and collect data on 88 total indicators (48 quantitative, 35 qualitative, and 5 process-level) related to the goals of the latest Education Development Strategic Plan. The results-focused approach aims to enhance internal accountability at all levels by avoiding conflicts of interest between policymakers and program managers.

Relevant, standardized, and comparable information about the quality of educational services in schools has been largely unavailable to stakeholders in the MENA region until very recently. In addition, critics have claimed that the region focuses too much on “engineering” education and too little on incentives and accountability relationships.

Stakeholders, however, appeared eager to employ new accountability strategies to address the triple whammy of the current learning crisis: low levels of learning, high inequality, and slow progress.

One proposed solution: The creation of a regional assessment agency to administer student assessments. The regional assessment could yield high-quality and comparable data across countries, replacing current national assessment systems recognized by participants as inadequate and misleading. The agency could be a cornerstone of accountability efforts and remedy the discouragement felt by countries from poor performance on international assessments.

While there are no global solutions to education, it is clear that stakeholders can leverage regional similarities, such as common language and cultural context, to address shared difficulties.

Commentary

There are no global solutions in education

November 14, 2017