In our last blog post we outlined some of the more pressing questions related to the use of data in education systems. This post provides more detail on how parents can be expected to use data to improve service delivery in their schools.

In recent years, transparency and social accountability reforms have gained traction in global education circles, building from a broader development agenda that encourages participatory processes and local empowerment. The general idea is that the availability of information at the school level can empower parents and communities to hold providers and governments accountable for delivering quality learning for all children. Interventions in this vein have varied from media campaigns in Uganda to an open data platform in the Philippines, citizen report cards in Pakistan, community monitoring in Niger, and school scorecards in India.

In a new report, we explore the underlying assumptions behind such information-based initiatives and assess the burgeoning evidence base for whether and how providing information to parents and schools in low- and middle-income countries can lead to improvements in service delivery and ultimately student learning. To do so, we draw from large-scale conceptual frameworks in the social accountability, open data, and governance fields; case study research from Moldova, Australia, Pakistan, and the Philippines; as well as a growing evidence base of impact evaluations.

From our research, six key lessons have emerged:

- Information is not enough. We echo much of the existing literature in finding that information alone is rarely sufficient to motivate parents to act or impel response from service providers. Instead, data must be made actionable by, for instance, using it to inform the joint-creation of school improvement plans between parents and school administrators, or offered in tandem with direct complaint hotlines for communities.

- What information is captured and how it is shared matters. Information needs to be user-centered to empower its audience to make meaning and act on it. This highlights the importance of selecting not only the appropriate indicators—whether on inputs or outputs—but also the most appropriate format. It matters that information reflects official standards or is placed in relation to similar contexts (for example, schools in the same neighborhood or serving the same kinds of students). Our research suggests that parents are more likely to act on information about school infrastructure and other inputs, whereas teachers and school principals find value in indicators about student learning.

- The use of “infomediaries” is vital. In cases where the ability of citizens to understand, process, and act on published information is constrained, intermediaries—for example, the media, civil society organizations, and researchers—can strengthen capabilities by translating and communicating information so it is more actionable for end users. These infomediaries can also play a vital role in articulating demand for data, working with governments to supply open data and engage in the reform process, and even in collecting and disseminating data on their own.

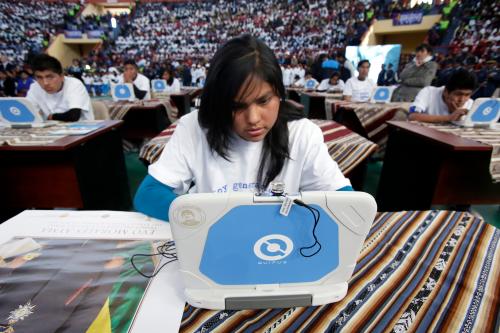

- Dissemination tools are as important as the source data. New technologies—social media platforms, text messaging, cloud services, tablets, mobile apps, and web interfaces—generate a lot of excitement. But this should not imply that more traditional means of communication are no longer useful, especially when faced with stark digital divides. A key first step in the design of information-based initiatives is testing the vehicle for its appropriateness for intended users.

- Pathways to change may be nonlinear. Often, transparency efforts are assumed to radically alter existing accountability relationships and processes. However, our research suggests that so-called “home runs”—interventions that unleash a dramatic increase in accountability—are rare. These insights stress the importance of working with the grain of embedded accountability relationships and with a deep understanding of complex political dimensions.

- Location matters. Transparency reforms must take into consideration the location(s) of decisionmaking and availability of resources, particularly in relation to local bureaucracies. Localized efforts must be integrated vertically, so that there is two-way communication between local actors and information and central resources and authority, rather than an approach where “scaling” prioritizes replication over integration.

The overall lesson here is not, of course, to suggest that putting information into the public realm is not valuable, but rather for practitioners, government officials, and donors that support transparency and social accountability efforts in education systems to realize that not all information is created equal. “Fit” must be taken into consideration to take full advantage of the opportunities that public information can generate. And, as highlighted in our last blog, reformers should be mindful that even successful interventions are limited in their ability to generate systemwide impacts on education and learning.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

6 lessons for using data to improve student learning in developing countries

January 26, 2017