The case for investing in American infrastructure is clear. It has one of the highest returns on investment the government can make, it employs about 11 percent of all workers and is a critical underpinning of a productive economy. Plus, key assets from bridges to water to schools are in dire need of reinvestment.

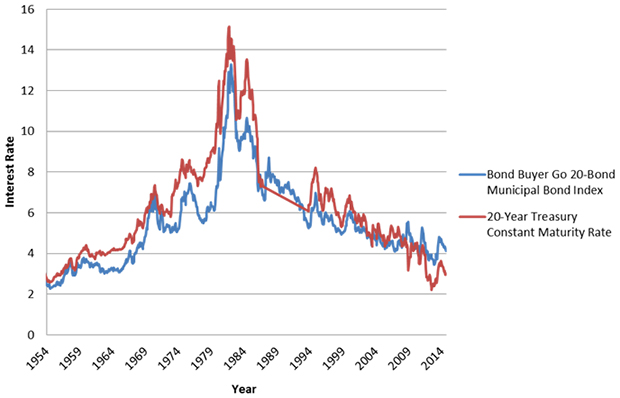

Yet, with 3 percent interest rates for 20 year federal debt and similarly low borrowing costs for most cities and states (excluding financial basket cases like Detroit, Illinois, and Puerto Rico), American investment in infrastructure is at its lowest percentage of GDP since 1950 and borrowing remains below historical trends. What is driving this disconnect between low cost financing and inadequate infrastructure investment?

Historic Interest Rates for Federal and Municipal Debt

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve Economic Data

Federal dysfunction is now a given, but state and local reluctance to tap low cost debt is perplexing. Six trends are shaping this debt aversion:

1. Political gridlock is not unique to Washington. Many elected leaders are averse to issuing new debt or raising new revenues needed to back bonds. Some of these anti-debt and anti-tax issues are reinforced by outside advocacy groups and local grassroots activism. However, even governments open to exploring new revenue, such as Missouri, struggle to find broadly acceptable mechanisms to drive new investment.

2. States and cities lack a supportive or reliable federal partner. The Highway Trust Fund is nearing insolvency and sequester cuts hit a number of EPA and Treasury programs that support infrastructure. While the majority of infrastructure spending is state and local, federal programs provide essential capital and credit support that accelerate project development.

3. Many states and cities are still dealing with the repercussions of the Great Recession. By and large, cities and states recovered from the recession, and many are even increasing their budgets. However, governments across the country dipped into rainy day funds, took on additional debt, and otherwise tightened their budgets, limiting their appetite for new debt.

4. Relatedly, large pension obligations and other post-employment benefits, like healthcare, take up a growing portion of state and local budgets and crowd out debt capacity for infrastructure investment. America’s 61 largest cities have only funded 74 percent of their pension liabilities and 6 percent of their health care liabilities.

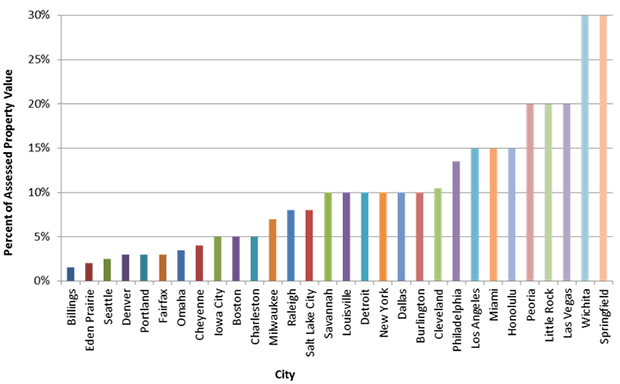

5. Statutory debt caps are another pressing issue. These self-imposed limitations on the amount of bonds a city or state can issue are usually capped at a percentage of the total value of taxable property in a given jurisdiction. While data on debt limits are difficult to attain due to inconsistent reporting standards, many cities in the Brookings network cited these caps—which can range from 1.5 percent to 30 percent—as a limiting factor.

Statutory City Debt Caps Around the United States

Source: All debt limits were pulled by Brookings from cities’ 2013 consolidated annual financial reports (CAFRs). Note that cities do not uniformly asses property values and that these limits may be selectively applied to different types of debt. For example, in some cities the limit may apply to all debt, but in others it may be limited to general obligation debt. Therefore, these values reflect general trends in debt limits and cannot be compared absolutely.

6. Traditional tax-exempt debt markets are only one way to raise capital. New estimates show that nearly 20 percent of all sub-national government debt issuances are now directly with banks, not through the municipal bond market. Concurrently, new models like public-private partnerships are gaining popularity. These new financing schemes are not uniformly captured in most disclosures, so states and cities may be taking advantage of cheap debt but it is not readily visible.

While no single factor is preventing cities and states from borrowing, policymakers need to think of creative ways to overcome each of these barriers to increase investment in America’s critical infrastructure systems.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Why Isn’t Cheap Debt Supporting More Infrastructure Investment?

October 30, 2014