Following President Putin’s visit to Beijing, Angela Stent and Yun Sun examine Russian and Chinese cooperation over the last two years, how China benefits from the relationship, and what to watch for as their economic, military, and diplomatic relations continue to evolve.

Transcript

PITA: You’re listening to The Current, part of the Brookings Podcast Network. I’m your host, Adrianna Pita.

Russia’s President Putin and China’s President Xi met again in China last week, reaffirming their country’s partnership as a counterbalance to the Western-dominated international order, while Russia’s war in Ukraine grinds into a third year. With us to discuss Russia and China’s relationship is Angela Stent, a nonresident senior fellow with the Center on the United States and Europe at Brookings, and also senior advisor for the Center for Eurasian, Russian and East European Studies at Georgetown University. And also Yun Sun, a nonresident fellow in the Global Economy and Development program at Brookings and John L. Thornton China Center, and also co-director of the East Asia Program and director of the China Program at the Stimson Center. Angela and Yun, thanks so much for talking to us today.

SUN: Thank you.

STENT: Yep, glad to be on your show.

PITA: I want to ask you both to start us off, Russia and China had signed this “no limits” agreement in 2022, shortly before Russia invaded Ukraine. How has that partnership played out over the last two years? And did last week’s meeting do anything to actually advance that? Or was it more symbolic? Angela, would you like to start us off?

STENT: Sure, thank you very much. Well, you have to note that the Chinese are no longer using the phrase “no limits,” and it certainly wasn’t used when Putin was in China recently. So for Russia, this has been the essential partnership that has enabled Russia to prosecute its war against Ukraine. Putin was in Beijing shortly after the full-scale invasion in February of 2022. And even though we understand that he did not explain the full extent of what the invasion would look like to Xi Jinping, he certainly understood that the Chinese would not oppose it. And so, what China has done is it has repeated the Russian narrative about the war, about why it started, that NATO’s to blame, and that Russia deserves what they call equal security. It has supplied increasingly Russia with components that are used in its defense industrial base, even as far as we know China has not actually supplied weapons to Russia, but it certainly has been an economic mainstay there. Trade with Russia has more than doubled since the war began. And China has largely backed Russia in international fora, although it still maintains a stance of neutrality.

I think that the recent visit by Putin to Beijing, it really solidified the relationship. There was a lot of very lofty rhetoric. Xi Jinping even embraced Putin at the end. But the Russians didn’t really get what they wanted to economically, at least as far as we know publicly. They really want the Power of Siberia 2 gas pipeline to be constructed to China and the Chinese have for a number of years delayed this and don’t seem to be very interested in it. Now I will say finally that we don’t know what was discussed privately. I would be very curious to know whether military issues were discussed privately that we don’t know about, possibly the Russian relationship with North Korea but if you look at what was at least publicly available, again there was a lot of flowery rhetoric and praise, I’m not so sure that much was accomplished.

PITA: Yun?

SUN: I pretty much agree with Angela in terms of her assessment of how this relationship has transpired in the past two years. We basically have seen an increasing alignment between Beijing and Moscow since the beginning of the Ukraine war. From the Chinese perspective, this is reflected in at least three different perspectives. One, we are seeing the strategic posture between China and Russia leaning toward each other, supporting each other at international fora and also advancing or advocating for each other’s positions on a number of issues from breaks to global south to the issue of Gaza. Secondly, we see that China adopts this, well, Angela called it neutrality, I call it pro-Russia neutrality in the war of Ukraine. And we are seeing that China defending Russia’s cause for starting this war quite vehemently in front of Europe and also at international fora like the United Nations. And last but not least, we saw this massive revenue creation from China towards Russia, especially through the Russian export of crude oil to China, which increased by more than 25% in the year of 2023, which boosted Russia from the number two supplier of crude oil to a very conspicuous number one, because Russia just surpassed Saudi Arabia in terms of the volume by almost 20%. So, we’re seeing that China creating a tremendous amount of revenue for Russia, which has sustained Russia’s ability to continue this war.

I think the Chinese have made it clear, they did not drop or publicly deny this no limit narrative that came out of Putin’s trip to Beijing in February of 2022. But I think they have added some limitations to it. So “no limit,” with limitation. And the specific term that has been used by senior Chinese officials is that there’s no ceiling between Russia and China in terms of the relationship. But there is indeed a floor, which means that there are certain boundaries and certain bottom lines that China will not violate in terms of its relationship with Russia. And I think this limited or the boundary of the cooperation that China is willing to provide to Russia, Angela mentioned the supply or the refusal to supply weapons and lethal aids to Russia and this rejection of Power of Siberia 2 are quite good examples of how this relationship does have limit.

PITA: Yun, as you just described, Russia gets more clear economic benefit out of this relationship, the increased trade with China, the continued gas and oil exports. How does China specifically benefit from this relationship? What are they getting out of it?

SUN: That’s a great question. There are indeed quite a few angles that China is benefiting from this relationship. The most important one being geopolitical. Because when China looks around, it looks at the United States and looks at this great power competition and look at the increasing isolation of China by the West. I think the Chinese see in Russia a partner that will keep China not as isolated as otherwise would be. So this geopolitics is always overarching factor when China looks at its relationship with Russia and makes a determination that we cannot abandon Russia and this alignment still serves China’s national interest in a very critical way. So that’s the first factor, the geopolitics.

Second one is energy. China remains to be, I believe, the number one importer of crude oil globally. And Russia does play a significant role in that equation. And I just mentioned that China’s import of crude oil from Russia increased by, I believe it was 26% in the year of 2023. But if you look at the value of that import, it only increased by 4%, which means that China has been importing Russian oil at a premium or lower than previous price. And this is significant for China’s energy security.

The third aspect is technology or technological cooperation. In the past, we know that China and Russia have engaged in a number of military technology transfers, Russian arms sales to China. So the military technological cooperation is still quite a big piece between the two countries. There are also cooperations in terms of nuclear. We know that Russia has been a large exporter of civil nuclear power plants to the world and it has a number of cooperation with China. There are also other areas of cooperation in terms of technology such as space, such as, for example energy implementation or energy exploration for example in the Arctic, so there are at least those three fields that China benefits from the relationship with Russia.

PITA: Angela, in some of the months leading up to this visit, there was some talk that Putin might have also had a visit to Vietnam attached to it. That didn’t wind up coming together, but what can you tell us about some of the other relationships that Russia is pursuing in addition to its close ties with China?

STENT: So, Putin has now cast Russia as an Asian power, which is something that the Soviet Union really never was. And partly, of course, because relations with the West are so bad. And so the relationship with Vietnam improved a number of years ago. Putin may not have visited it now, but that is an important relationship for both countries. But I would say maybe one of the most interesting ones is this new Russian-North Korean relationship. I mean, in the Soviet times, the Soviet Union, of course, financed North Korea in many ways and even though actually no Soviet leader visited North Korea, they still had close ties. Soviet Union collapsed, that support went away, it was very difficult for North Korea. North Korea has now emerged as a major supplier of artillery for Russia in its war with Ukraine. It’s enabled Russia to pursue this war more effectively than it did before. And you have had the North Korean leader Kim Jong-un visited Russia last year. He’s very interested in return for the ammunition, the artillery that the Russians are getting from the North Koreans, clearly the North Koreans want sophisticated technology. They’re interested in rockets and things like that. And the Kremlin has announced that Putin is going to visit North Korea. He hasn’t done it yet. His first visit post-presidential reelection, if we’re going to call it that, was to China.

And then the other thing I think to note is beyond Northeast Asia, the Russian-Indian relationship has always been important, but that has been in some way strengthened since the war with Ukraine began. And India, like the other BRICS countries and like a number of countries in what we call the Global South and what the Russians call the world majority, have not taken sides in this war. They haven’t sanctioned Russia and they don’t really see why the West, Europe and the United States, should force them to take sides in what they see as a European conflict when they believe that the West doesn’t pay very much attention to their own conflict. So, Putin has emerged from this war, one could arguably really with stronger ties with a number of these countries in the Global South, particularly since the Israel Hamas war began. But I would say China is the kind of bedrock of all of these newer relationships. And it’s the one without which Putin wouldn’t be able to do what he’s doing.

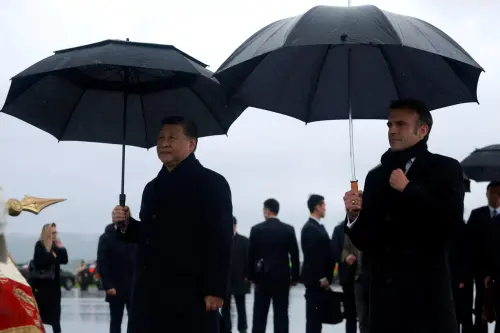

PITA: Yun, Putin’s visit comes not long after Xi’s recent trip to Europe. He visited Serbia, Hungary, and France. As the EU has started pursuing its strategy of de risking, reducing dependence on China for certain high tech and clean energy imports, what’s the state of China’s current economic relationships in Europe?

SUN: The current state of the relationship is that while it’s still going strong — so last year, China was, I believe, the second largest trading partner of China was with EU. The largest one was ASEAN. And also China, I believe, is also Europe’s second largest trading partner in the year of 2023 — we are seeing some fluctuation in terms of the European investment in China. But I think that’s closely associated with this campaign for this desire to de-risk from an over-dependence on either the Chinese market or the Chinese suppliers in the global supply chain. Especially in certain high-tech areas, we have seen, for example, the chip alliance among US, Japan and Netherlands. And in terms of the clean energy-related imports, last year 40 % of China’s EV electric vehicles were exported to Europe. So that really signifies the importance of Europe as a market and also as access to the high technologies available, that are still available to China. So the relationship is important for Europe, especially for nations that emphasize trade in their economic growth. And here I think Germany is always on the top of the list because Germany, I believe, one third of German GDP depends on foreign trade. So, China as the single largest market in Asia and some would argue globally, plays a significant role in European countries’ economic calculus.

But having said that, I think the issue of Russia and the issue of the war in Ukraine does play a significant role and one would argue an increasingly more critical role in China’s relationship with Europe. Because the Chinese certainly understand that the war has not put China on Europe’s good side. And there is a strong desire from the Chinese part to retain the affinity or positive feelings from Europe towards China. And that’s why we’re seeing that the Chinese leaders or Chinese senior diplomats repeatedly trying to reassure Europe that while China is neutral and China is trying to mediate, and that gets to the most interesting part of this trip, which is, well, what is European message towards China on the war in Ukraine and Russia’s next step strategy towards war. And here I think German Chancellor Scholz, he visited China before the end of April. And I thought that his trip was much more interesting in terms of the manifestation of where Europe and China both stand on this issue. So German Chancellor Scholz tried to convince China to join this peace conference that will be hosted in Geneva in June. A peace conference that in the past that China has rejected to participate. The Chinese did not completely shut the door on Europe’s face this time. In fact, it says, well, we’re willing to keep the communications open on the issue of a peace conference and China is willing to make its contribution towards a peace conference. What we know the problem with these European peace conferences on Ukraine is that Russia has consistently refused to participate. And China also has not participated in the peace conferences hosted in Europe either. So I think there is an interesting dynamic here because the Chinese position was the message is that, well, Europe if you do want Russia to participate in the peace conference you will have to be more realistic about your position, and you will also have to be more careful about not completely adopting Ukraine’s position on how this war should end. So there is an interesting bargaining that we’re seeing here, that China telling Europe that you need to lower your expectation and lower your asks and maybe we can bring Russia around at an opportune time. And if you look at how this issue has been framed in the Xi-Putin meeting during this Putin’s visit to Beijing, I think it is going in that direction. Russia said, well, we’re not completely rejecting the idea and we would be happy to participate at a time that we see as a good opportunity. So I think this is something that I will be watching for moving forward. Thank you.

PITA: Angela, Putin recently entered into his fifth term in office. I think we’re going on 25 years now. And he recently changed up some of the Cabinet personnel at the start of this term. What sort of signals are you getting from some of those changeups that happened there?

STENT: Yeah, thank you for the question. Let me just add that Russia hasn’t been invited to any of these peace conferences and China did attend the first one in Jeddah and the second one as well. Yun Sun is right that they didn’t attend the one that was in Davos. And this is a peace conference that’s based on the Ukrainians’ 10-point peace plan. The Chinese have their own peace plan, which is much vaguer, but it’s something that the Russians have praised. Anyway, we will see whether China does attend the meeting in Switzerland.

So I think Putin’s Cabinet reshuffle, the most interesting part of it was the elevation of Andrei Belousov, who is an economist, and has had various positions as a first deputy prime minister and other economic positions in the government. And he elevated him to be defense minister. And Sergei Shoigu, who was a defense minister since 2012, was reassigned. He’s now the head of the Security Council. And the long-term head of the Security Council, Nikolai Patrushev, if you like, was moved upstairs and was made an advisor to Putin on shipbuilding. So you might ask, why has an economist been put in charge of the defense ministry? He has no military experience and he doesn’t have any base in the defense ministry. But he has really been put there for a number of reasons. Russia is on a war economy footing and he has been really put there to make sure that this war economy functions well, that the army, that the military get what they need in terms of equipment. He’s also supposed to deal with corruption, of which there’s been a great deal in the Russian military, with money disappearing into people’s pockets, money that should have been spent on training soldiers and also on equipment. And he’s been also put in charge to kind of integrate the civilian economy with the war economy and answer to the demands of the people who run the military industrial complex. Whether he’s going to be able to do that or not is unclear. Otherwise, the heads of the two intelligence agencies have been left in place, even though — the foreign and domestic intelligence — even though they made huge mistakes in the run up to the Ukraine war by giving Putin false information about the fact that the Ukrainians would welcome Russia and that they were just waiting to get rid of President Zelenskyy. There are a couple of younger people who’ve been promoted and I suppose we will watch them to see whether they might be potential successors. But so far, I think the message is definitely from Putin that he intends to be in power for a very long time and that he intends the war to go on for a very long time and that Russia is at war with the West.

PITA: I want to wrap us up by having you talk a little bit, both of you, comment on what you, sort of what you’re watching for as the relationship moves forward, if you see any potential friction points on the horizon. Yun, do you want to start us off? And then we’ll give Angela the last word.

SUN: Sure. Well, on the issue of the peace conference, yes, you are right, Angela. China participated in the peace conference in Jeddah last summer, but China rejected the invitation to participate in the peace summit in Budapest earlier and also in Davos earlier this year. So I think the Chinese are very clear that the peace conference needs to be participated by both Ukraine and Russia, and these two parties need to be treated on somewhat of an equal footing, which will be a really high bar. So it’ll be interesting to see where that goes.

In terms of China-Russia relations, I thought that one interesting development is on trade. That we have seen basically the bilateral trade doubling itself between 2019 and now. So, China’s trade with Russia is quite significant. It’s more than 200 billion U.S. dollars. And from this, Putin’s trip to Beijing, we’re seeing that the two leaders have vowed to bring their trade relationship, bring their economic relationship to a new height. And you have to wonder, what would that come from? Because the majority of the trade between China and Russia have been in energy supplies. And there is that much, there is a limitation to how much China can absorb. One of the reasons, the key reason that China is rejecting the Power of Siberia 2 is because China’s ability to absorb natural gas is limited and currently it cannot have the capacity to absorb more. So if the two countries are going to bring their trade to a new level, and to advance it further, what are they going to trade? We know that China has been selling Russia, for example, electronic vehicles and other machines and electronic appliances that China has to offer. But from the Russian perspective, energy is the biggest piece and there is almost nothing else. So looking into the future of this relationship or this economic relationship, one has to wonder about the sustainability and how much growth or how much space for growth, it still has left remaining. Thank you.

PITA: All right. Angela?

STENT: So, I’ll also be looking at the military relationship. There’ve been rumors for some time that there will be more of a, if it’s not called a military alliance, at least closer military ties, they’ve been doing more joint maneuvers together. I’ll certainly be looking at that. Obviously, I’ll be looking at the economic relationship. And then I think when Putin was in Beijing, one part of the declaration he signed with Xi Jinping was repeating what the permanent five of the UN have said, that nuclear war can never be won and must never be fought. Putin obviously has used nuclear rhetoric fairly often since the beginning of this current war with Ukraine and he’s announced that the Russians are doing some tactical nuclear weapons drills or will be doing them soon. Xi Jinping has at least once publicly chided Putin for using this kind of nuclear rhetoric and so as time goes on, as this war goes on, I’m going to be watching that and seeing what, again, what is said in the public domain. And then, you know, both Russia and China are committed to this so-called post-West global order, and they’re both pushing, you know, to have a world where the United States no longer, as they see it, is the hegemon, can no longer call the shots, and that they have much more of an input into it. I think Russia and China have a different definition of what a post-West global order will look like, if you listen carefully and read what they and their colleagues say. But I think that’s something to watch, kind of the push towards a world where the U.S. plays a lesser role and China, particularly, in the BRICS, but in other organizations, assumes much more responsibility, and whether the Russians are willing to accept this since they are definitely the junior partner in this relationship.

PITA: All right, Angela, Yun, thank you very much for your time today.

Commentary

PodcastThe dynamics of the Russia-China partnership

May 22, 2024