When the story of U.S.-China relations is written, historians may give special focus to September 2018. Heading into this month, the relationship already was on a sharply downward trajectory, due to actions by both sides. Coming out of it, there is a growing possibility that leaders in Beijing and Washington may come to view each other no longer as acute competitors, but increasingly as implacable foes.

Prior to this period, mutual frustrations had been building. In the United States, the sharpness of President Trump’s complaints that China is plundering American wealth have intensified as it has become clear that his tariffs will not reduce the trade deficit or deliver Chinese structural economic reforms—rather, they’ll hurt farmers, factory workers, and small business owners. Members of Congress have been ringing the alarm about China’s attempts to manipulate public discourse. And many Democrats on Capitol Hill, like their Republican colleagues, have developed sharply negative views about China’s illiberalism at home and activism abroad.

In China, amusement over President Trump’s unconventional style has given way to anger.

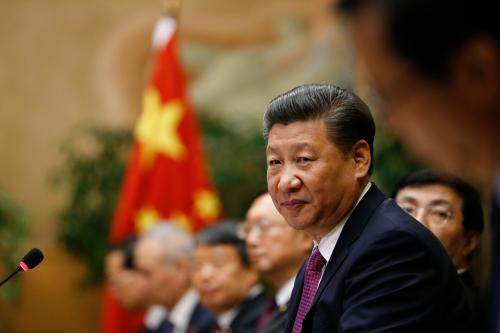

In China, amusement over President Trump’s unconventional style has given way to anger that Trump is attempting to damage China’s economy, derail China’s rise, and delegitimize China’s leadership. Many in Beijing also have complained that Trump is scapegoating China for America’s own domestic challenges. According to this logic, Beijing has no incentive to accommodate President Trump’s demands on trade or any other issue, because Beijing judges that doing so would not address the underlying motive of Trump’s actions—to knock down America’s nearest peer competitor.

The tenor of the relationship changed in late September, though. First, the United States launched a fusillade of actions against many of China’s most vulnerable points. These actions included implementation of a $200-billion unilateral tariff package, an arms sales announcement to Taiwan, a Congressional resolution on Tibet, public censure of China’s repression of ethnic Uighur citizens in Xinjiang, publicized B-52 bomber operations in the South and East China Seas, the first sanctions on the People’s Liberation Army since the Tiananmen incident in 1989, and the announcement of a new policy requiring America-based members of China’s state media to register as foreign agents. While it is unclear whether the simultaneity of actions was by design or coincidence, officials in Beijing invariably will see them as elements of a coordinated campaign.

Such views will be reinforced by President Trump’s broadside against China while chairing a meeting of the United Nations Security Council September 26. At that event, and in subsequent public comments, President Trump accused China of interfering in America’s electoral process. When pressed for evidence, President Trump thus far has only offered that Chinese media bought inserts in an Iowa newspaper and that China targeted its tariffs to hurt voters in electoral districts that previously supported Trump.

While such actions by China are unwelcome and most likely counterproductive to China’s goal of compelling Trump to lower the temperature on trade tensions, they are not unique. Many countries routinely purchase inserts in newspapers and magazines, and many of America’s closest friends similarly have imposed geographically targeted tariffs in retaliation to Trump’s trade actions.

So, from Beijing’s perspective, by singling out China and accusing it of “interfering” in America’s election on the basis of actions that multiple other countries have taken, Trump may be setting the predicate for blaming China for expected electoral setbacks this November. Members of the Trump administration may take their cue from the president in the coming weeks and build a public case that China is an enemy of the American people. There also may be further punitive measures against China. China almost certainly would counter-punch. If such a sequence comes to fruition, there is real risk in the coming months of accelerating descent into enmity between the world’s two most powerful countries and largest trading nations.

As the bilateral relationship deteriorates, President Trump will have less leverage to influence Beijing. He no longer will be able to warn Xi privately of the risk of a rupture in relations if China takes actions that implicate vital U.S. interests. Trump also will not be able to count on the support of any ally anywhere in the world for pursuing a purely confrontational approach toward China. Even countries most wary of China—like Japan, India, and Australia—will not risk economic ties with China. To the contrary, these countries have been hedging against American unreliability by working to stabilize relations with China.

Instead, the policy tools President Trump will be left with include threats, penalties, public pressure, and the possibility of horizontal escalation—taking action on issues of importance to Beijing to induce pressure on China to capitulate to American demands. If the relationship goes down this path, the present period of heightened tensions could become a way station to conflict.

President Trump’s supporters will argue that previous administrations’ efforts to pursue a balance of cooperation and competition only served to enable China’s rise, and therefore, Trump is justified in shaking things up and pursuing a more confrontational course. Such logic rests on a false choice between maintaining the status quo versus racing headlong down a fruitlessly dangerous path.

The Trump administration is right to challenge unacceptable Chinese behavior. China’s efforts to discriminate against U.S. firms, turn back the tide of economic reform, bully American allies and partners, improperly manipulate American public discourse, and violate the basic rights of its own citizens merit a forceful American response. Such a response will have more impact, though, if it is focused on specific concerns and embedded within a demonstrable effort to manage the world’s most complex and consequential bilateral relationship, rather than as an element of a strategy to define China as an enemy.

Washington also needs to find its friends around the world who share similar concerns about China’s behavior, and who are willing to push back on specific issues that implicate their interests. Beijing will feel more pressure to moderate its behavior at home and abroad if it faces a chorus of criticism from around the world than if it believes it needs to hunker down to fend off the Trump administration’s attempts to undercut China’s sociopolitical stability.

The U.S.-China relationship may be approaching an inflection point. The choices that leaders in Washington and Beijing make in the coming weeks may have a lasting effect on whether each side sees in the other a challenger and competitor with whom it remains possible to maintain generally stable relations, or an implacable foe that needs to be undermined.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Why is Trump accusing China of election interference?

September 27, 2018