“Tell me how to stay alive and sane in a world that clearly just doesn’t care about us having a future.” This is what a child and adolescent psychologist reports hearing more and more frequently. No wonder, given that the world is confronting a cascade of human rights violations and brazen massacres of people in an increasing number of conflicts, while at the same time falling short on collective action to deal with climate change, biodiversity loss, and pandemics.

At a time when our generation boasts unprecedented know-how and wealth, why are we so stuck?

The latest 2023/2024 Human Development Report argues that it is because we are unable to manage the challenges of living in an interdependent world, as put in sharp relief during the COVID-19 pandemic. Whatever happens to the future of globalization, interdependence will persist because of two drivers. The digital revolution and dangerous planetary change. Interlinked global challenges are outpacing our willingness and our institutions’ ability to respond to them.

One of the key reasons for us being stuck is paralyzing political polarization. It has increased since 2011 in two-thirds of the world’s countries. Polarization is not about differences in what is best for society. Rather, it is about societies becoming divided into opposing and belligerent camps, poisoning domestic and international cooperation. This results in the gridlock of the report’s title, frustration with the political system, and disenchantment with experts and science.

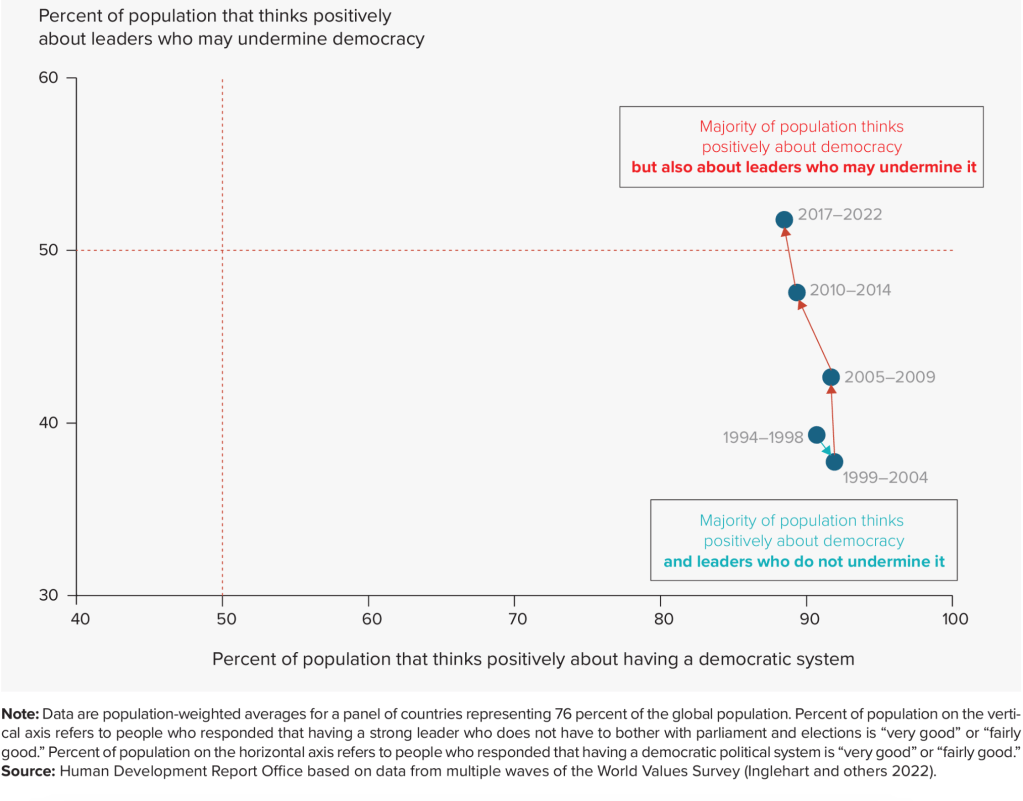

The confluence of real economic hardship and insecurity, interacting with a polarization in beliefs about what should be done on issues ranging from vaccines to climate change, fuels this polarization. The vote for populist parties (anti-elite, hostile to international cooperation) in Europe. And while nine in ten people globally have consistently shown unwavering support for democracy, there has been a steady increase this century in the support of leaders who may undermine it: Today, for the first time ever, more than half the global population supports such leaders (see figure below).

Figure 1. The democracy paradox? Unwavering support for democracy but increasing support for leaders who may undermine it

Distrust and polarization are kneecapping our ability to summon the cooperation needed to address shared challenges. As political polarization festers it poisons discourse and public reasoning. Turning what is one of the most valuable ingredients of any healthy society—diversity of views and policy positions—into an excuse for populism, othering, and authoritarianism, that results in gridlock.

The report suggests three ways forward.

1. Ease polarization by recognizing that there is more common ground than typically assumed

We agree on more than we think we do. For example, close to 70% of people around the world are willing to make a personal financial sacrifice to address climate change but think that only 43% agree with them.

Gridlock emerges because collective action depends not only on what one privately thinks about an issue, but also on how each of us believes others around us think about the same issue. The world is living in a false social reality. Piercing this fog of pluralistic ignorance is one of the most effective ways of changing behavior to encourage cooperation to address shared challenges.

2. Empower individuals with greater control and voice

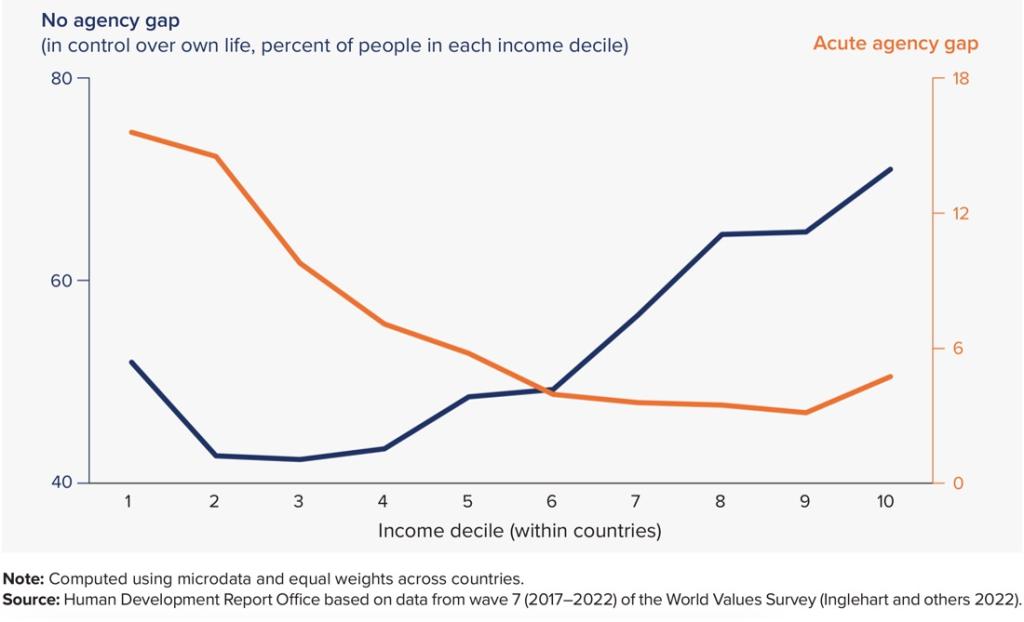

The report highlights the importance of empowering individuals by making them feel more in control of their lives and giving them a stronger voice in shaping their collective future. Currently half of the world’s people do not feel in control of their lives, and two-thirds feel that they do not have a say in their political system. Moreover, this perceptions of lack of agency are shaped by income: There is a steep decline in the share of people reporting having very low control over their lives for the bottom 50% of the income distribution (orange line in the figure below) and the share of people reporting having very high control of their lives is low and fairly equal for the bottom 50% of the income distribution, but rises for deciles 6 and above (blue line in the figure below). Redressing income inequalities would thus be a way of enabling people to have more agency—or narrowing what the report calls agency gaps.

Figure 2. The perception of agency (control over one’s own life) is shaped by income

Agency gaps are also associated with perceptions of insecurity. Fear paralyzes and polarizes. Evidence suggests that higher perceptions of insecurity lead to larger agency gaps and lower levels of trust in others. Thus, in addition to tackling inequalities, insecurity (real and perceived) needs to be addressed directly to narrow agency gaps and improve trust.

3. Build an architecture for global public goods

The report suggests creating a framework that supports the provision of global public goods—things like climate change mitigation and communicable disease control, in which one country’s benefits do not detract from others from doing the same. Today’s challenges, and more importantly, those of the future, require cooperation at a global scale as we confront unprecedented planetary challenges from climate change to biodiversity loss, and as the digital revolution that links our economies and societies deepens. The provision of global public goods does not assume that all differences and tensions between countries will go away, but rather that it is possible to identify arenas of cooperation in aspects that that are not zero-sum.

This framework implies reimagining international cooperation as something more than development assistance (supporting poor countries) and humanitarian assistance (saving lives in emergencies). International cooperation needs also to deliver global public goods, and low- and middle-income countries need access to finance their contributions to these global public goods, consistent with their development aspirations, on tendentially concessional terms. Multilateralism plays a fundamental role, because bilateral engagements are not able to address the irreducibly planetary nature of the provision of global public goods. Moreover, the inadequate provision of global public goods can, in itself, drive further inequalities between and across countries. This is exactly what happened in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the world failed to provide the global public good of controlling the spread of a novel virus. It is also what projections indicate will happen as a result of climate change.

If the world makes progress on these three proposals, even if they cannot be implemented overnight, perhaps children and young people may stop saying that they are living in a world that doesn’t care about their future.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

3 proposals to advance human development: Charting our interdependent future

April 3, 2024