This viewpoint is part of Foresight Africa 2024.

The future of conservation is one in which local economies, nature, and people—the soul of these landscapes—can flourish.

As an old king from the floodplains of the Kwando River in Angola used to say, “A landscape without people is just a landscape. But a landscape with people, has history and soul.”

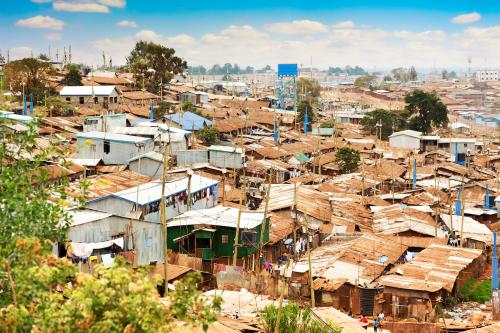

Much of the African continent’s natural environment is largely undisrupted for a variety of reasons—including about five centuries of a disrupting colonization process, independence conflicts, and political instability, among others. And while it might seem counterintuitive, one of the most important reasons it remains undisrupted is because of people—and their unique traditions, beliefs, and cultural connections to their own environment and natural heritage.

It is well known that Africa has been the least polluting continent over the past hundred years. The African continent possesses some of the largest and least disrupted ecological regions and natural landscapes in the world. Few places have nearly untouched mosaics of biomes and such vast landscapes with still thriving naturally occurring biodiversity and natural monuments and resources.

And while the developed world has contributed the most to the global climate crisis, the Mother Continent has been acting as the counterweight—nurturing our natural resources, our ecosystems, and our people, who are equipped with creative solutions.

The African population’s usage of natural resources and their intrinsic relationship with the natural elements should be considered an example of sustainability at its best. For example, Africa has five of the most important naturally occuring “water towers” of the world—in Ethiopia, Angola, Lesotho, the Lufilian Arc, and the Albertine Rift—elevated surfaces that store large quantities of water. And thanks to local communities, these water towers are largely intact—up until now, at least. In the Angolan Highlands Water Tower (AHWT), we find ourselves in a unique and delicate position.

Water is now becoming the most valued resource in the world. An average of 423 cubic kilometers of rainfall falls over the AHWT each year—which amounts to nearly 170 million Olympic-size swimming pools. This water provides food and water security and sustains the livelihoods of millions of people in seven countries—Namibia, Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, the DRC, and the Congo. It also feeds some of our continent’s most iconic wildlife and ecosystems, including the Okavango Delta, which is home to the largest remaining population of elephants on the planet. While this may seem like an infinite amount of water, we must manage this resource carefully. Angola—like many emerging African economies—faces rapid population growth, which could strain our water resources.

Recent research from the National Geographic Okavango Wilderness Project (NGOWP) has defined the boundaries of the AHWT within academic science for the first time, a much-needed step toward formal protection. NGOWP’s data shows that we could better manage our water resources. It also finds the AHWT is surrounded by peatlands covering an initial estimate of 1,634 kilometers squared (around 600 miles). Located across Africa’s largest miombo forest, these peatlands sequester millions of tons of carbon every year and contribute to climate resilience, which has a positive impact on economic growth.

But that research only builds on what the local communities in the area have known for millennia.

This is a familiar narrative: More and more, scientific research and understanding has been building on traditional knowledge that has been passed from generation to generation for thousands of years. Long before academic scientists were introduced to these landscapes, rural communities in Africa have been acting as Guardians of their own environments—with their own beliefs, traditions, myths, and unique understanding of natural processes and cycles. From our experience, the key is valuing both Africa’s natural and cultural richness and heritage.

Instead of creating new systems of protection, which are often based on concepts and ideals from a Western worldview, I urge leaders to work within existing systems of protection helmed by local communities. The global community can adopt and adapt these intricate and holistic systems that are part of our roots in a way that elevates them and positions local communities as the stewards of their own lands, of their own futures. We must also move away from protection and conservation done in a way that separates people from their ancestral lands and denies them access to their own natural resources and landscapes. These neocolonial approaches to conservation will only exacerbate and aggravate tensions due to scarcity of resources and result in further local conflicts, diverting people from thinking and focusing on the way forward.

The future of conservation is one in which local economies, nature, and people—the soul of these landscapes—can flourish. We can all contribute to the African continent becoming a pillar of this paradigm shift and an exemplar for development in its true sense. It is time to give back to Africa what it has limitlessly given to the rest of the world, as the Mother it is.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Why we can’t overlook people in addressing climate change

March 28, 2024