Introduction

Public safety and the economy are among the top priorities for mayors, governors, and state legislators in 2025, just as each is important to the public. These issues come as a new federal environment aims to shift a greater share of federal costs and responsibilities to states and localities—placing these two levels of government at the center of the nation’s ability to deliver effective services and programs that address constituents’ key concerns.

To make inroads on public safety and economic security, it’s worth noting that far too often, both the public and policymakers treat these two issues separately. Crime reduction efforts are primarily focused on policing and justice system reforms, for instance, while job creation and economic prosperity remain largely the remit of economic development and other related policy levers.

Further, when it comes to issues of crime and public safety, recent public attention has largely focused on fixing problems in cities, even when prior research has found troubling safety challenges in rural and suburban communities as well.

One result of this fragmented approach has been a new wave of policymaking centered on restoring “law and order” in cities, which has largely prioritized policing, penalties, and prisons as the primary deterrents to crime. At the state level, this includes efforts to exert state control over local police departments, curtail the powers of local prosecutors, and roll back criminal justice reforms aimed at shrinking the size of the incarcerated population. At the local level, some cities are also embracing this pivot through policies to increase prosecutions for low-level crimes, embrace “stop and frisk” policing practices, and enact youth curfews in the name of public safety.

At the same time, regional leaders have been critical partners and investors in strengthening American innovation and economic prosperity. Coalitions of business, civic, university, government, and nonprofit actors are pursuing transformative regional initiatives that boost next generation industries and jobs. Many of these efforts have attracted private sector capital, especially in economically distressed places—demonstrating that the path to global competitiveness runs through cities, towns large and small, and their regional partners.

Rather than silo public safety and economic development efforts such as these, research and practice point to the benefits of aligning these objectives to make lasting, systemic progress on both safety and opportunity—particularly in disinvested and “left-behind” communities, whether urban or rural.

Consider this: According to recent Brookings research, it was the loss of jobs and educational opportunities for people living in high-poverty neighborhoods that primarily explains the rise in homicides during the COVID-19 pandemic—not changes in policing or criminal justice system practices. Further, a large body of evidence finds that approaches linking public safety efforts to those bolstering employment, education, and quality neighborhoods can measurably reduce and prevent violent crime, while also saving taxpayers and governments significant costs.

Importantly, the connection between public safety and economic opportunity is not new for many practitioners working directly on violence reduction in both cities and rural communities. For instance, after speaking with incarcerated people in Cook County, Ill.’s jail, former U.S. Secretary of Education and Managing Director of Chicago CRED Arne Duncan offered this insight on what they said it would take for them to put down their guns: “What I heard dozens and dozens of times was a job for $12 or $13 dollars an hour…If we could employ people and give them a chance to heal, get their high school diplomas and grow, they will make that choice. They’re happy to make that choice.”

Local law enforcement officers we spoke to agree.1 In Ohio, one police officer told Brookings researchers, “Whether it’s an urban area with gangs or a rural area with trailer parks, crime comes down to depressed economics. Some people, especially single moms, are working five jobs and when their kids come home. Nobody’s there. It’s not because they don’t care, it’s because they can’t be there. But young people still want a family atmosphere. They’re looking for mentorship, people that care about them, and family. That’s what gangs provide. Think of FOE [Family Over Everything].2 You could take the worst part of the city here and take the worst parts of the rural county where I grew up and they’re the same. The violence, the addiction, the theft—it’s the same. It’s just that one is rural, and one is urban. People don’t see that.”

These reflections demonstrate the power of economic distress and youth hardship in driving crime in “left-behind” communities, regardless of whether these places are urban or rural. They also reveal that while there is a strong need to improve the criminal justice system itself, there are risks to ignoring the compounding trauma from poverty and systemic lack of opportunity that leads to the contagion of violence in the first place. This is particularly true as the challenges of persistent neighborhood poverty, financial precarity, chronic absenteeism, and youth mental health are only increasing in both large cities and less densely populated suburban and rural communities.

Therefore, the current surge in public interest to address both public safety and economic opportunity offers a ripe moment for state and local leaders to work together and blend criminal justice reforms with community-centered economic strategies that improve safety and well-being in communities large and small. To better aid state and local leaders in this imperative, this paper presents new analysis from 10 U.S. states (Georgia, Indiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas, and Wisconsin) and evidence-based recommendations to address the intersection between place, public safety, and the economy.

Specially, this report finds:

- Crime is not limited to cities, but varies widely across cities, suburbs, and rural areas, with some suburbs and rural areas reporting higher per capita crime rates in recent years than urban peers.

- There is a strong relationship between place, economic opportunity, and public safety in cities, and a similar relationship can be found across select suburban and rural areas.

- Investments in youth, families, and neighborhood revitalization can mitigate crime and help break the cycle of violence in communities over the long run.

With crime and the economy being top concerns for families and businesses, the paper closes with ways in which state, regional, and local leaders can join forces in ways that make a tangible difference for safety and economic growth in urban, suburban, and rural communities alike.

Why focus on state and local policy, and why now?

This report focuses specifically on state and local officials for three key reasons. First, crime is a hyperlocal issue—meaning rather than directly affecting residents of a given state, region, or city equally, it disproportionately concentrates in specific neighborhoods and streets where economic and place-based disadvantage also cluster.

Second, the nation’s approximately 18,000 law enforcement agencies are governed by state and local laws, and 88% of the nation’s incarcerated population is under state control. States enact their own legislative reforms and investigations into policing and criminal justice, and importantly, many of the preventative investments needed to improve public safety are under the purview of local governments. Moreover, state and local governments also have significant control over the economic, community, and workforce development tools that are needed to address the drivers of crime.

Third, state and local leaders will need to take an increasingly salient role in violence prevention amid today’s shifting political and fiscal climate at the federal level. As pandemic-era federal relief funds for gun violence prevention and economic development run out, federal offices such as the Office of Gun Violence Prevention shutter, and the future of federal agencies overseeing crime reduction undergo significant changes, state and local leaders will be at the forefront of thoughtfully designing, implementing, and tracking outcomes for public safety interventions and policymaking.

Background: How data limits our understanding of public safety in most communities

Stories of inner-city crime often dominate the public debate, but most of the country’s population (61%) lives in rural and suburban areas.3 Thus, national attention on public safety should capture the crime trends and experiences of people living in suburbs and small towns too.

Yet data limitations make the task of understanding rural and suburban crime difficult.4 Of the 16,000 agencies that reported crime data to the FBI in 2023, for instance, less than half (just 7,349) were local law enforcement agencies. This presents a challenge for understanding safety trends given the localized nature of crime, and an even more significant challenge for rural law enforcement agencies with less capacity for crime reporting. According to our analysis, these local reporting agencies cover only 53% of the U.S. population.

Map 1 demonstrates the variation in the share of the urban, rural, and suburban populations represented in FBI national crime statistics across 50 states in 2023. Notably, there were no broad-based differences in data coverage for Democratic- or Republican-led states (with the exception of lower coverage rates among Southeast and Appalachian states). However, our analysis found that across the United States, reported crime data covers 84% of the urban population, while only being available for 33% of rural and 33% of suburban populations.

Figure 1 shows the share of the population represented in crime data by locality type (urban, rural, suburban) for the 10 states we studied—finding significantly lower rates of rural and suburban coverage than that of their urban peers (with the promising exception of Massachusetts).

It is often said that what gets measured gets done. The majority of Americans live in suburbs and rural areas, but just one-third of these communities benefit from sufficient local crime data reporting, limiting the ability to craft tailored public safety solutions for them.

Although recent efforts such as the Real-Time Crime Index and NORC’s Crime Tracker have made significant strides in addressing some of these data challenges (particularly in larger areas), persistent data gaps remain and pose a significant barrier for state and local policymakers in developing the right kinds of public safety initiatives. In particular, low rates of reporting among rural towns and suburbs run the risk of outsized attention to crime in large urban areas, while under-resourcing crime reduction efforts in smaller localities.

Data and methodology

This piece analyzes FBI Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) data from 2019 to 20235 (2023 being the most recent year available) to present crime trends across select urban, suburban, and rural localities in 10 U.S. states.6 While there are limitations with FBI data (including the reporting time delays, lack of full reporting from local law enforcement agencies, and the fact that not all crimes are reported to the police and therefore are not captured in police data), this paper utilizes UCR for several reasons: 1) FBI UCR data offer the most complete data source for comparing crime trends across localities of different sizes (namely, the ability to compare rural and suburban crime trends with those of their larger urban counterparts, which often publish local data more frequently); 2) The data utilize standard definitions of crime categories, which vary across jurisdictions; 3) The FBI has significantly improved its reporting coverage in recent years; and 4) Findings from the 2023 UCR dataset align with findings from the other primary data source for comparing rural and urban crime rates, the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), in terms of national trends for 2019 to 2023. While local law enforcement data would provide more timely data (since the FBI typically releases year-end trends in September or October of the following year), it is not available for a broad swath of suburban and rural areas, rendering it less useful for comparing trends across localities of different sizes.

This paper analyzes data from localities in 10 states, chosen for the ability to provide sufficient data to compare crime trends for at least one rural, suburban, and urban locality in the years before and after the COVID-19 pandemic (2019 to 2023). These states also offer representation from different geographic regions and party governance.

In each of the 10 states, we analyzed crime trends from three localities—one rural, one urban, and one suburban (in the same MSA as the urban area)—with sufficient data to compare property and violent crime trends between 2019 and 2023. We also analyze how each locality compares to statewide and national crime trend averages. To broaden our analysis outside of these 10 states, we also selected a set of large cities that are often called out for high crime rates—Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C.—to provide additional comparisons that can help inform public understanding.

Given extensive data limitations, this analysis does not seek to make claims about one locality type (urban, rural, or suburban) being “safer” than the other. Rather, it strives to document the significant nuances that characterize crime trends across the diverse landscape of places that compose the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Finding #1: Crime is not limited to cities, but varies widely across cities, suburbs, and rural areas, with some suburbs and rural areas reporting higher per capita crime rates in recent years than their urban peers

The U.S. is at an important turning point in public safety trends. After decades-long declines in crime, the nation experienced one of the largest increases in murders ever recorded in 2020. Since 2023, crime has fallen dramatically nationwide and murder rates have mostly returned to pre-pandemic levels (or below), especially in most cities. Even with this progress, crime remains too high in many communities, particularly in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty—a challenge that remains stubborn and persistent even amid yearly fluctuations in crime rates. Furthermore, public fear of crime remains higher today than at almost any other time this century.

Our findings seek to enhance knowledge of recent local crime trends in specific urban, rural, and suburban localities across 10 states for which there are sufficient data from 2019 to 2023. Across the 10 states studied, we found significant variation in crime patterns, reinforcing the need for policymakers to understand that the prevalence and growth of crime are not limited to cities, but pose significant challenges for rural and suburban areas as well, particularly in the Southern U.S.

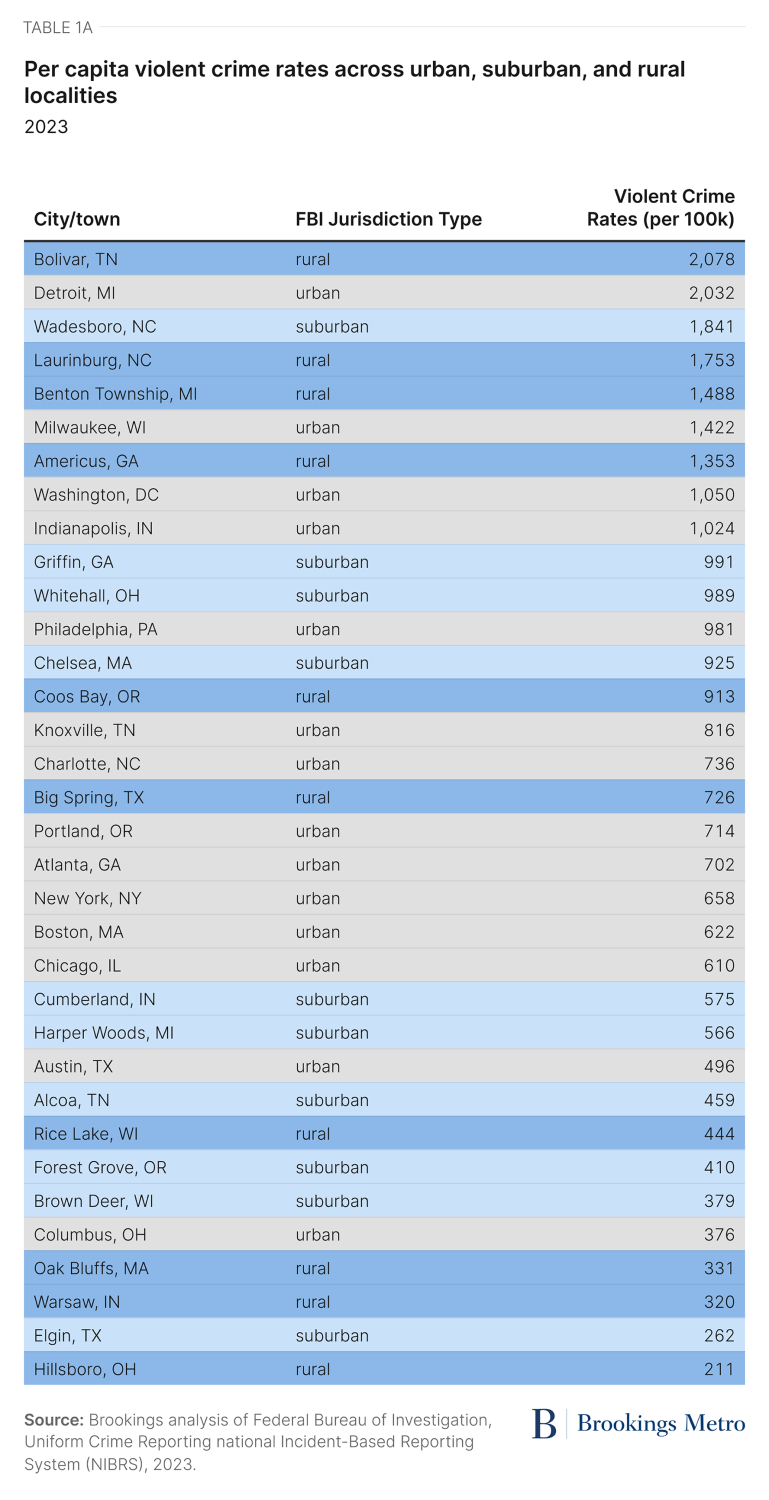

As Table 1a demonstrates, suburban and rural localities analyzed in North Carolina, Ohio, Tennessee, Texas, Georgia, Massachusetts, and Oregon had higher rates of violent crime than their urban counterparts. These jurisdictions also exhibited higher rates than those found in the U.S. cities often blamed for driving violent crime, such as Chicago and New York. The rural town of Bolivar, Tenn. (population 4,888), for instance, provides a demonstrative example: In 2023, the town had a per capita violent crime rate more than twice that of its urban counterpart in Knoxville and more than three times that of Chicago. The rural town of Laurinburg, N.C. (population 14,928) also had a violent crime rate more than twice that of its urban peer, Charlotte, and 3.5 times higher than Austin, Texas.

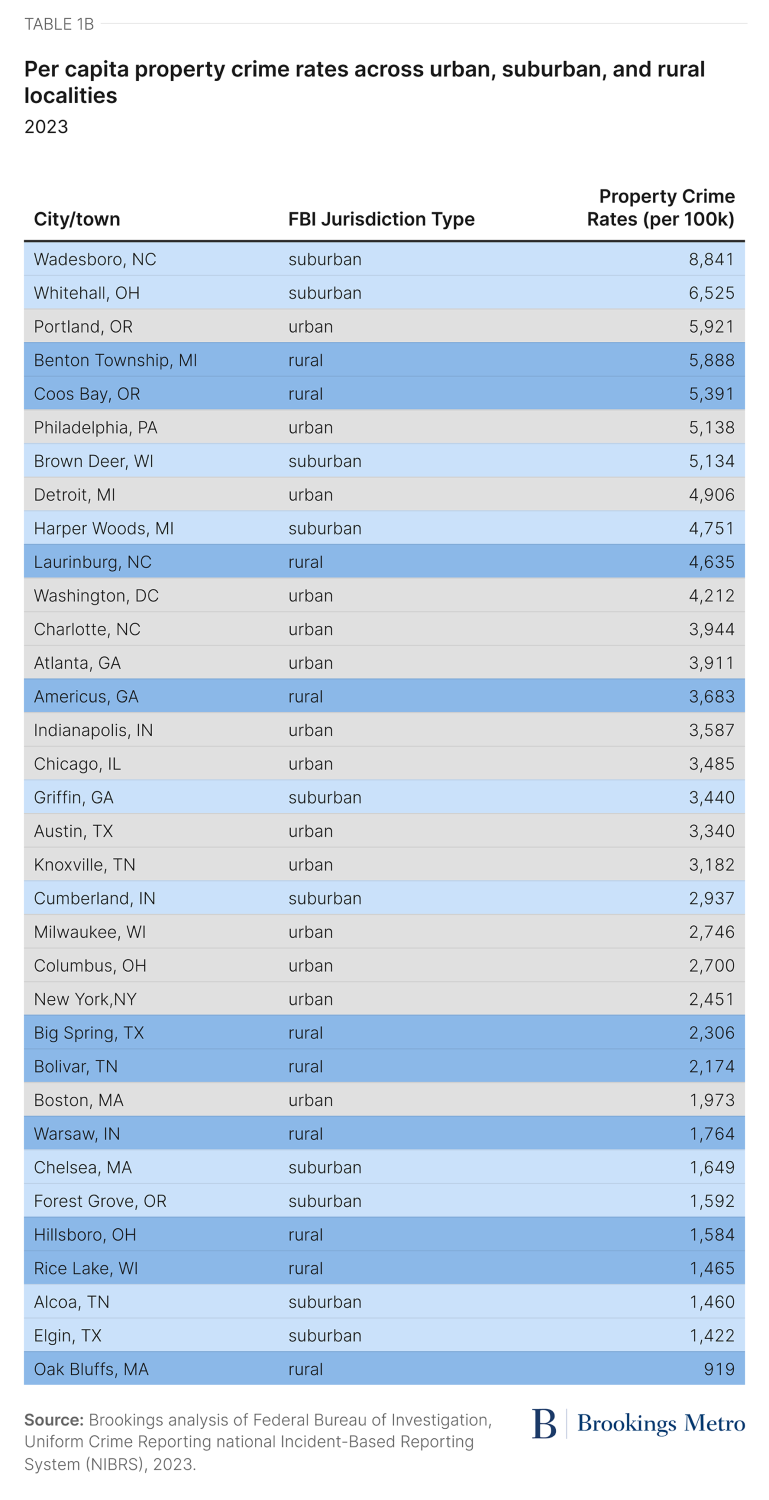

A similarly complicated picture emerged for property crimes. Studied suburban and rural areas in Michigan, Wisconsin, Ohio, and North Carolina had higher per capita property crime rates than urban areas in their states, as well as higher rates than cities such as Milwaukee, Washington, D.C., and Chicago. In 2023, the suburb of Whitehall, Ohio (population of 19,816), for example, had a property crime rate more than twice that of the state capital, Columbus, and over three times that of Boston.

Of course, comparing per capita crime rates for a single year only provides a limited glimpse in time. To gauge localities’ progress on crime reduction in the years since the pandemic, we also examined crime trends from 2019 to 2023. The interactive map in Figure 2 provides property and violent crime rates for a set of localities in our 10 study states between 2019 and 2023, revealing a patchwork of progress and setbacks across urban, rural, and suburban areas alike. To see trends across the 10 states, navigate the interactive map in Figure 2, which displays trends in both violent and property crimes since the pandemic, as well as how these trends compare to statewide averages.

Figure 3 illustrates the kind of visual data one can find in the map interactive. Specifically, in the state of North Carolina, the suburban town of Wadesboro has experienced significant increases in property crime since the pandemic, while the rural town of Laurinburg has disproportionately struggled with violent crime. Rural communities in North Carolina experience, on average, higher per capita property crime rates than the state average.

Figure 4 demonstrates the overall change in crime rates since the pandemic across the localities in our sample. On the whole, available data indicate that suburban areas in our sample disproportionately struggled with property crime, while urban areas struggled with violent crime. However, rural and suburban areas had significantly more variation in their crime trends across the sample.

It is important to note when interpreting these trends that in localities with a small baseline of crime, spikes in incidents may appear drastic, but overall crime rates could be lower than state or national averages. Even with this caveat, however, prior research indicates that even small increases in low-crime areas can significantly impact the public’s perception of crime and safety in their region.

Finally, to mitigate some of these data limitations, we examined how our sample compares with national crime averages. Figure 5 demonstrates that, on the whole, urban and rural areas across the entire spectrum of local reporting agencies had higher violent crime rates than the national average, while suburban areas in the sample had significantly higher property crime rates than the national average. These trends must again be taken with significant caution, as 84% of the urban population is covered by reporting agencies, while only 33% of the rural and 33% of the suburban population is covered.

Taken together, our analysis reveals significant variations in crime data reporting and trends that make it difficult to make summary statements about the locus of crime in the country. The greater concentration of available data and media coverage in cities makes it easier to spotlight urban crime, even when most residents live in suburban and rural areas. However, this analysis reveals that where there is data available for suburban and rural communities, these communities confront public safety concerns too. By following the data, one finds that there is potential for lawmakers and leaders from diverse sectors and geographies to join forces in supporting common, place-centered public safety solutions for communities of all sizes.

Finding #2: There is a strong relationship between place, economic opportunity, and public safety in cities, and a similar relationship can be found across select suburban and rural areas

It is well established that within large urban areas, poverty, neighborhood disinvestment, and segregation are strongly correlated with higher rates of violent crime. In fact, recent Brookings research found that in a typical U.S. city, homicide rates in high-poverty neighborhoods are 3 to 4 times higher than in other residential areas in the same city (see Table 2).7

Notably, sample cities with the lowest shares of homicides occurring within high-poverty neighborhoods—such as Austin, Texas and Portland, Ore.—also have a relatively lower share of citywide residents who live in high-poverty neighborhoods (11% and 6%, respectively). This aligns with previous research demonstrating that poverty alone is not always a predictive factor for high rates of gun homicides, but rather it is the intersection between poverty, segregation, and systemic disinvestment that concentrates violent crime in place.

While this kind of granular, neighborhood-level crime data is unavailable for rural and suburban areas, evidence indicates that many of the characteristics that drive the relationship between poverty and violent crime—including diminished work opportunities, weaker professional networks, exposure to environmental hazards such as lead paint and air pollution, and greater numbers of abandoned businesses and empty lots—exist within lower-income rural and suburban places.

Indeed, when looking at the intersection between poverty and violent crime in our select rural and suburban towns, we find a similar relationship. As Figure 6 shows, the five small localities with the highest rates of violent crime also have significantly higher poverty rates than their peers. The relationship is less consistent than within urban areas, but merits additional attention from state and local leaders, particularly as suburban poverty has intensified across regions in recent decades.

The presence of concentrated poverty is one proxy for the quality of economic opportunities in a community. There is other evidence that points to the role that economic conditions in places play in either contributing to crime or reducing it. For instance, the loss of manufacturing jobs, diminished generational economic mobility, and greater economic inequality can contribute to elevated levels of crime in a community.

At the same time, the presence of serious crimes within a community can cause depopulation and economic hardship as families move to safer places. On the other hand, reductions in crime can generate significant economic benefits to communities from increased home values, budgetary savings from reduced spending on law enforcement and justice system services, and additional revenue from taxing incomes earned by those who would otherwise be involved in crime or be in prison.

Finding #3: Investments in youth, families, and neighborhood revitalization can mitigate crime and help break the cycle of violence in communities over the long run

If lack of economic opportunity in specific neighborhoods and places is highly associated with elevated crime in communities, then it naturally follows that expanding opportunity in targeted places should help reduce crime and improve safety. In that regard, a large body of research, rooted in the evaluation of real interventions, reveals the importance of opportunity-creating policies and interventions that can meaningfully address crime and the economic factors contributing to it.

When we say “opportunity-creating,” we mean the roles of employment, education, workforce development, and neighborhood revitalization that together enable jobs, small businesses, and household incomes to grow, which then has a positive impact in mitigating crime. These interventions, when paired with targeted efforts to intervene and reduce violence among high-risk individuals in the near team, can help break the cycle of violence in high-poverty communities over the long term.

Three key policy areas have shown significant progress in advancing both public safety and economic mobility:

- Bolstering employment, job training, and other financial security programs. Youth workforce development and job programs have been found to reduce violent crime arrests by as much as 45%, making them one of the nation’s most effective public safety programs. Evidence indicates that this efficacy applies to adults as well. Workforce training, education, and support interventions are particularly effective in reducing recidivism among reentry populations. Providing short-term financial assistance is also associated with crime reduction, as is increasing access to rental housing for low-income families. At the state level, decreasing unemployment corresponds with significant reductions in property crime, while increases in the minimum wage correspond with reduced recidivism rates among justice-involved individuals. Importantly, these interventions can be applied in cities and rural areas alike, with small communities such as Danville, Va. leading on youth workforce initiatives that connect youth with mentorship, apprenticeships, and employment opportunities, and recruit participants to become “ambassadors” who represent their neighborhoods in city meetings and provide input on the city’s strategic plan.

- Engaging, educating, and supporting youth. Investing in positive youth development—whether through workforce training, school programs, early childhood services, mentorship, or other interventions—is one of the most impactful ways policymakers can support long-term community safety outcomes. In addition to youth jobs programs, evidence-based interventions include: targeted efforts to increase youth educational attainment; programs to support youths’ social and emotional well-being; and quality after-school programs. Importantly, the benefits of investing in youth can begin early, with both early childhood intervention programs and nutrition programs for newborns being found to reduce crime over the long term.

- Improving the neighborhood conditions that contribute to crime. Community and economic development investments can also have significant crime reduction benefits. By implementing built environment and quality-of-life improvements within neighborhoods—for instance, by revitalizing abandoned buildings, increasing access to parks, investing in community-based nonprofits, and improving lighting and other aspects of the public realm—cities and towns can significantly reduce violence. In Philadelphia, an effort to transform and clean vacant lots in high-poverty neighborhoods led to a 29% reduction in violent crime, while a program to remediate abandoned homes was associated with a 39% reduction in firearm assaults. The presence of street lighting, painted sidewalks, public transportation, and parks is also significantly associated with decreased odds of homicide. Place management and government organizations in commercial corridors, such as business improvement districts and Main Street organizations in particular, can bolster resources for crime prevention and services in commercial corridors—leading to improvements in both real safety outcomes and perceptions of safety.

Importantly, these investments in jobs, youth opportunity, and quality places work best when combined with focused community and law enforcement partnerships to solve local murders, deter violence, and identify and reengage people already involved in violence. Such efforts include community violence intervention programs, which identify individuals currently involved in violence or at high risk to do so and connect them to services such as therapy, mediation, and other critical supports. These programs have been shown to reduce violence-related arrests by as much as 73%.

Moreover, many of these interventions are both cost-effective and focused on root causes, meaning that by following the evidence, state and local leaders can employ solutions that embrace both conservative and progressive values.

Policy recommendations: How state and local leaders can work together to systematically reduce crime and expand economic opportunity

As this paper has shown, public safety is not solely an “urban” problem, but rather a shared challenge across communities large and small that requires shared, evidence-based solutions. As state and local lawmakers craft their priorities for 2025 and beyond, the renewed public interest in safety and an economy that works for everyone offers them a strong opportunity to address their constituents’ top concerns in tandem.

The good news is that state lawmakers and local leaders can look to proven approaches that effectively address these intertwined challenges through collaboration. In fact, crime reduction strategies that pair law enforcement reforms with education, employment, and community development strategies enjoy bipartisan support among state leaders, law enforcement, and progressive organizations.

However, the rush to politically respond to pandemic-era spikes in crime has yielded a renewed wave of tough-on-crime solutions at the state and local levels, with less attention to prevention strategies and collaborations within cities and regions and between states and localities. In fact, in some states, tensions are rising over expanded state powers in local policing and local prosecutor oversight.

Rather than chase short-term wins or, worse, ineffective strategies that can make crime worse, state and local leaders should leverage this moment to commit to what the data and evidence demonstrate—that there are enormous upsides to collaborating around violent crime reduction strategies that also improve the economic potential of people and places across cities, small towns, and urban-rural regions. This means pursuing cross-sector collaborations within cities and regions and between states and localities—collaborations that break down the silos between public safety and economic opportunity. And when states cooperate with their big cities, they enable their economic engines to flourish.

The following captures some of the novel efforts underway to link the goals of public safety with economic growth, employment, educational opportunities for young people and adults, and neighborhood revitalization. The nation needs to reward more of these kinds of collaborations to make sustained progress on the twin goals of crime reduction and economic expansion.

- Strengthening local public safety efforts with private and public sector partnerships to enhance economic opportunity

Across the nation’s cities and towns, local leaders have made new efforts to align violence reduction and public safety strategies with investments in economic opportunity, education, and workforce development. Below are three demonstrative examples.

- Public-private partnerships to reduce crime and invest in youth in Birmingham, Ala.: In the wake of two high-profile mass shootings in Birmingham in 2024, elected officials, regional business leaders, and community-based partners came together to form the Birmingham Crime Commission, aimed at providing comprehensive recommendations for reducing gun violence in the city. The Commission, chaired by two prominent business leaders in the region, explicitly called for the business community to take a more active role in supporting violence reduction through investments in workforce development and youth-focused initiatives, including Birmingham Promise, which provides college and career opportunities to students in Birmingham City Schools. The Commission’s recommendations include both immediate actions to target and reduce violence through law enforcement strategies as well as long-term recommendations to confront the socioeconomic disparities that contribute to Birmingham’s high crime rates, including addressing high unemployment rates and limited opportunities for youth in the most vulnerable neighborhoods. By prioritizing a “community-centered safety framework” that addresses the root causes of crime through investments in education, jobs, workforce development, and housing, the Commission has carved out a clear path for the economic development community to be meaningful and impactful partners in this effort.

- Private-sector-led collaborations aim to reduce violence through hiring and economic investments in Chicago: Business-led organizations in Chicago are expanding economic opportunities as a strategy to reduce gun violence, which is highly concentrated in the city’s South and West sides. The Corporate Coalition of Chicago is a growing alliance of 50 employers (including Hyatt, United Airlines, Mars Wrigley, Allstate, and others) that have come together with the express purpose of changing business practices in hiring, procurement, and capital investment in ways that will reduce long-standing economic and racial inequities in the region. For example, the Coalition leads a fair chance hiring initiative that is helping employers change company policies and practices to hire individuals with arrest and conviction records. The Coalition’s Corporate Connector program taps corporate talent to support South and West side organizations, entrepreneurs, and small businesses. In partnership with the Chicago Community Trust, the Coalition is developing a fund to help change the community development financing marketplace so local developers investing in catalytic real estate development projects have routine access to affordable, patient equity capital. At the same time, the Civic Committee of the Commercial Club of Chicago, the region’s premier business-led membership organization, has launched a public safety task force. Its goal is to identify ways the business community can help make Chicago the safest big city in the country. The task force has a four-pronged strategy, which includes an ambitious 20,000-job hiring goal for residents of the South and West sides while marshaling business resources for investing in community economic development in those communities. The Civic Committee’s strategy also includes support for scaling community violence interruption programs and direct investments in improving the effectiveness of local law enforcement.

- Taking a “whole of government approach” to advance safe and opportunity-rich neighborhoods in Baltimore: In 2021, Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott released the city’s first Comprehensive Violence Prevention Plan, which prioritizes a public health approach for reducing violence and engages the entirety of city government—from economic and community development to education to policing—as critical in advancing public safety. In the four years since, the city has significantly increased capacity for its community violence intervention programs and funding for neighborhood revitalization and investments in youth—including adopting a $120 million vision for increasing access to recreation and parks in high-crime neighborhoods; allocating $21.3 million to employment initiatives that serve youth, such as YouthWorks; strengthening youth career opportunities through additional Mayor’s Office of Employment Development programming; and bolstering workforce development training and other services for returning citizens. These investments are showing promising results: In 2024, the city saw a 23% decrease in homicides, which followed a 20% drop in 2023.

Similar efforts to merge local crime reduction efforts with broader investments in workforce, education, and economic development are taking place in cities and towns across the political spectrum—ranging from the small town of Danville, Va. to cities such as Baton Rouge, La. and Cleveland, Ohio—and can serve as a model for bipartisan, collaborative approaches to public safety.

- Bridging regional economic development strategies with place-based efforts to improve public safety

Across the country, consortia of business, civic, university, and nonprofit partners have come together to advance good jobs, technological innovation, and shared prosperity as the hallmarks of global competitiveness. But unlike past regional economic development strategies, many of these efforts include intentional strategies to invest in talent development and neighborhood revitalization in historically underserved communities that also disproportionally struggle with challenges of crime and safety.

- Engaging justice-involved individuals in the transition from coal to clean energy in Southern West Virginia: Beginning in 2021, a coalition of regional leaders and community-based organizations in West Virginia’s Coalfields region came together as part of the Economic Development Administration’s Build Back Better Regional Challenge to tackle a cascade of economic and public health challenges brought on by the region’s economic decline from coal dependency and widespread job losses. The regional effort—targeted across 21 rural Appalachian counties—sought to not only repair economic opportunity in the region through investments in clean energy, but also address the significant consequences of a targeted opioid crisis that plagued the region and left many of its residents with criminal justice records. As a cornerstone of this regional effort, the West Virginia-based community development organization Coalfield Development scaled its 33-6-3 workforce development model, which aims to prepare the regional workforce, which has been heavily impacted by both wealth extraction and the trauma produced by substance abuse and incarceration. This model has strong potential to be adapted to other rural and coal-transitioning regions. In 2018, for instance, the World Bank highlighted Coalfield’s model as highly relevant to coal-impacted communities across the U.S., Europe, and China. The West Virginia Community Development Hub’s role as a statewide intermediary devoted to rural community and economic development has also been highlighted as a national model for “doing development differently,” and provides a concrete approach for investing in rural communities to build their capacity, tackle systemic barriers to growth, and drive systems-level change that local leaders in rural areas of all kinds can learn from and adapt to their unique local contexts.

- Advancing inclusive innovation and talent development across urban, rural, and tribal communities in Greater Tulsa, Okla.: Led by Tulsa Innovation Labs, the Tulsa region has a vision to drive inclusive economic growth by positioning it for strength in future industries such as virtual health, energy tech, cyber, and advanced aerial mobility. As it does so, regional leaders’ strategy includes a major emphasis to ensuring that historically underserved populations are part of future innovation and growth. On innovation, this includes initiatives to drive new, diverse-owned startups and extend tech adoption to rural communities in partnership with Native American tribes and Black-led entrepreneurship groups. On workforce, the region has set a goal to make sure one-third of jobs are accessible for people without a college degree, and that the average job pays a living wage. On placemaking, the strategy involves supporting Black Tech Street and building an AI Co-Innovation Space in Greenwood Avenue District, the historically Black neighborhood affected by the Tulsa Race Massacre in 1921 and destroyed by subsequent urban renewal in the 1960s. Thanks to the region’s vision, Tulsa has garnered almost $90 million in federal grants, winning both the Build Back Better Regional Challenge ($38.2 million) and a Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs award ($51 million) while attracting private capital and partners, all with the support of the state.

- Strengthening workforce development and inclusive growth across Western New York’s urban-rural divide: Western New York—anchored by the cities of Buffalo, Jamestown, and Niagara Falls, and comprised of diverse rural communities across the region’s Southern Tier—was once a hub of steel and industrial manufacturing. Today, Western New York grapples with high levels of poverty and segregation, both within its urban core and surrounding rural towns. Within Buffalo, poverty and segregation are concentrated in the city’s East Side, with more than half of individuals living in or near poverty, and over 85% of Black residents concentrated in those neighborhood due to a history of redlining and other racially discriminatory investment policies. Within the predominantly rural Southern Tier, residents also face severe economic hardships and barriers to accessing quality pathways to economic opportunity. In 2021, a regional coalition of economic development, community, and anchor institution leaders embarked on a regional effort to tackle this challenge head-on through strategic investments in workforce development and place-based revitalization that aim to connect underemployed residents with advanced manufacturing opportunities. Building on successful efforts to stand up the Northland Workforce Training Center on Buffalo’s East Side—which provides advanced workforce development training and supports for the broader region, including to underserved young people and returning citizens with barriers to employment—the regional coalition expanded its workforce model to the rural Southern Tier. To do so, they partnered with Goodwill of Western New York to offer hands-on training, wrap-around services, and job-placement services for underemployed residents in rural areas across Western New York, and conducted targeted recruitment efforts to engage hard-to-reach unemployed people in rural communities through a strong “boots on the ground” presence. By blending a mix of state, federal, and local funds, the region is embarking on a bold regional workforce initiative that aims to combat patterns of economic disinvestment across the urban-rural divide and ensure that underemployed residents can access quality jobs regardless of where they live.

These case studies provide only a snapshot of how regional economic development initiatives can address the economic and workforce challenges that contribute to violence in both urban and rural communities, with other examples ranging from Central Indiana to Appalachian Ohio to Philadelphia. Notably, however, these efforts require intentional and meaningful engagement with residents in high-violence communities to ensure that design and implementation result in long-term structural change.

- Going beyond policing to align state and local priorities in bipartisan legislation

In addition to supporting innovative local and regional partnerships, there is a strong role for state leaders to prioritize policies that not only reduce crime, but also foster more opportunity-rich communities. Several states are already leading in this regard, especially in the following three arenas.

- State policies to bolster workforce and economic opportunities for returning citizens: Much of the recent state-level momentum on safety and economic opportunity has focused on enhancing workforce and job opportunities for people returning to society after incarceration. Importantly, both Republican- and Democratic-controlled legislatures have taken on this critical task. In 2023, for instance, Arkansas passed the Protect Arkansas Act, a bill that aims to reduce recidivism and improve employment by providing incarcerated people with digital education and employment records, high-quality education and training programs, connections to in-demand job opportunities, and community-based re-entry services. States such as Tennessee and Colorado have recently passed occupational-licensing reform to allow formerly incarcerated people to obtain better-paying jobs, while the Tennessee, Arizona, and Utah legislatures all passed legislation requiring their states’ Department of Corrections to equip individuals leaving incarceration with a state ID or driver’s license, Social Security card, and birth certificate to help reduce barriers to employment. State officials in Minnesota have championed the potential of the 2023 Minnesota Clean Slate Act to improve the state’s economy and bolster its workforce by reducing the barriers to employment for the nearly 1 million Minnesotans with criminal records.

- State investments in strengthening youth and families: Another key priority for state legislatures has been to reduce the harm that violence and justice system involvement can produce for youth and families. In 2025, for instance, the Kentucky legislature introduced the Family Preservation and Accountability Act to expand alternatives to incarceration for caregivers convicted of nonviolent offenses and provide them with vocational training, educational programs, and other resources to help to keep families impacted by incarceration together. States such as Michigan and Illinois have passed reforms for youth with juvenile justice system involvement to better access employment (through expungement) and financial stability (by reducing fines and fees). And on the prevention side, states such as Alabama, Colorado, and Indiana are expanding youth apprenticeship programs for underserved youth to access long-term, paid, work-based learning opportunities and structured educational curricula to increase their pathways to quality, high-paying jobs.

- State-level infrastructure for comprehensive violence reduction: Just as improving public health requires addressing social determinants outside the health care system itself, there has been growing recognition among state leaders that addressing violence requires coordinating investments and policies across a broader range of institutions outside of criminal or juvenile justice departments. To this end, since 2019, over a dozen states have established a state-level Office of Violence Prevention to coordinate and govern multidisciplinary investments in education, workforce, economic development, and public health to reduce violence and other forms of crime. Importantly, many states with these offices—including North Carolina, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and others—have significant rural constituencies as well as major cities within their borders, both of which struggle with crime and can benefit from coordinated governance structures. By investing in state-level infrastructure through the creation of statewide offices of violence prevention, states are better equipped to ensure that the crime-reduction efforts unfolding in both rural areas such as Robeson County, N.C. and in large cities such as Charlotte, N.C. can benefit from aligned, strategic investments to address the root drivers of violent crime.

In short, states have a powerful role to play in creating policies and investments that supplement the comprehensive local approaches underway to mitigate crime and expand opportunity.

Conclusion

Concerns about public safety are serious, as are concerns about disparities in economic security. This is exemplified by the experiences of places such as Birmingham, Ala.: When public and private sector leaders there came together to determine how best to address crime, they looked to research, best practices, and the input of residents, including those most impacted by crime. What they learned from community members was the desire for the following: clean and well-maintained neighborhoods; access to community resources such as affordable housing; job placement and workforce development programs; youth mentorship and after-school programs; and a stronger police presence in collaboration with community members.

In short, what residents would like to see from state and local leaders is a mix of interventions that blend short-term policing strategies with investments in jobs, youth, and quality neighborhoods—priorities that are often shared across communities large and small.

Given today’s climate—with the public exhausted by the nation’s politics and federal funding for violence prevention and place-based economic development uncertain—state and local leaders have an opportune moment to demonstrate that problem-solving and cooperation is possible. This report adds to the data and evidence that states and localities can use to chart an evidence-based, effective path for not only reducing violence in America, but also advancing broad-based prosperity and economic growth across the “urban-rural divide.”

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors would like to sincerely thank the following experts for their contributions to and reviews of various drafts of the piece: Tony Pipa (Brookings Institution), Rhett Morris (Common Good Labs), Gbenga Ajilore (Center on Budget and Policy and Policy Priorities), Andrew Papachristos (Northwestern University), and Brian Fabes (Corporate Coalition). In addition, they want to thoroughly thank Benjamin Swedberg (Brookings Metro) for his excellent research contributions to the piece.

-

Footnotes

- Brookings conducted qualitative interviews with public safety stakeholders in Akron, Ohio in January 2025 and was granted permission to anonymously use this quote.

- “Family Over Everything” refers to a criminal organization that the U.S. Department of Justice identifies as affiliated with the Ohio-based T&A Crips gang.

- The FBI uses the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) designations for classifying cities, suburbs, and nonmetro areas, which define urban areas as having a population of at least 50,000 and being located within a MSA; suburban areas as having a population of less than 50,000, located within a MSA; and rural areas as having a population between 10,000 and 49,999 and existing outside of a MSA.

- Three years after the FBI changed its reporting to prioritize the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS)— which requires greater detail on crime incidents, leading to higher–quality and more useful data—over 16,000 state, county, city, university and college, and tribal agencies submitted data in 2023, covering 94.3% of the total U.S. population in 2023. While this is a significant improvement from the three years prior, many local law enforcement agencies still have not made the switch to the new NIBRS system, meaning there are significant blind spots in the nation’s ability to understand local crime trends that aggregate statewide or countywide statistics can obscure.

- Data comes from the FBI National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) State Tables, Offenses by Agency

- The FBI uses the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) designations for classifying cities, suburbs, and nonmetro areas, which define urban areas as having a population of at least 50,000 and being located within a MSA; suburban areas as having a population of less than 50,000, located within a MSA; and rural areas as having a population between 10,000 and 49,999 and existing outside of a MSA.

- “Neighborhoods of concentrated poverty” are defined as residential areas where at least 30% of the population lives below the poverty line.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).