Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

In this India-U.S. Policy Memo, Shamika Ravi discusses the problems that plague India’s education system and identifies areas in which India and the United States can cooperate to find solutions.

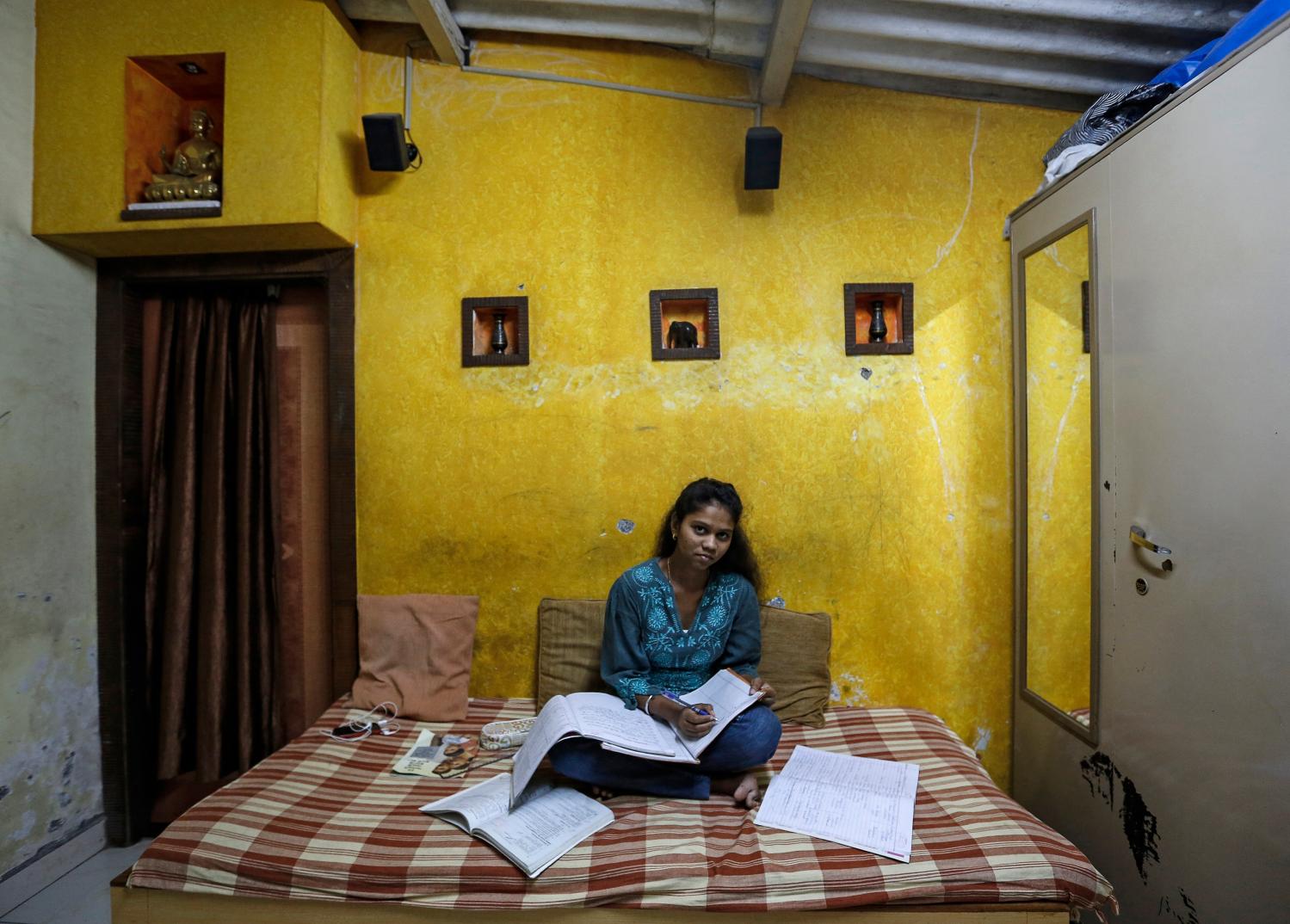

Over the last 20 years, we have witnessed an explosion of aspiration among the Indian youth, who are also among the biggest supporters of Prime Minister Modi. Access to quality higher education is the launchpad for the realization of those aspirations and dreams of young India. College and university education, however, remain off-limits for many talented Indian students. Increased numbers of school graduates are opting for college education but the shortage of quality higher education institutions has led to sky-high cut-off marks for admission and the proliferation of dubious illegal institutions. Compared to China, access to higher education in India looks dismal. In 2000, the gross enrolment ratio in higher education—the number of individuals going to college as a percentage of the college-age population—was 8 percent in China and 10 percent in India. In less than a decade, this rose to 23 percent in China but in India, this rose only marginally to 13 percent, reflecting the extreme shortage of higher education institutions.

It is now well accepted that the U.S. is the undisputed superpower when it comes to university rankings where it dominates almost every such list, significantly ahead of other countries including Germany and the United Kingdom. At the same time, not a single Indian university has featured in the top 200 either in the QS World University Ranking or in the Times Higher Education rankings. India’s best universities are Delhi, Hyderabad, Mumbai, Calcutta, and Madras but none of them make it into the global rankings. The Indian Institutes of Technology and Indian Institutes of Management are centres of excellence in teaching but have low research productivity and are not universities. It is estimated that nearly 100,000 Indian students today study in American universities. While this reflects the superior quality of higher education institutions in the U.S., it is also a strong indicator of the low capacity of the Indian higher education system. A natural area to strengthen India-U.S. ties, therefore, would be in the higher education sector. India can start by exploring ways to increase investment in the higher education sector and by ensuring that the quality of teaching is world class, with an overriding objective of making higher education accessible to anyone with the talent for it.

Areas in which bilateral cooperation should be explored:

Financing: This is a major bottleneck in the Indian higher education system. With pressures to cut fiscal deficits, and tight central and state government budgets, there is an extreme shortage of resources that are necessary for expansion of access to higher education to all those who deserve it. While the Indian government has allowed foreign universities to open campuses in India, several regulatory constraints and manoeuvring a cumbersome bureaucracy remain serious impediments. As a result, not a single foreign university has made an independent entry into India.

Teaching quality: The quality of a higher education degree is only as good as its curriculum and the quality of the teachers. Indian universities are unable to compete with rising private sector salaries and find it difficult to recruit and retain top quality teachers. This is an area where India can learn from the vast positive experience of the U.S.

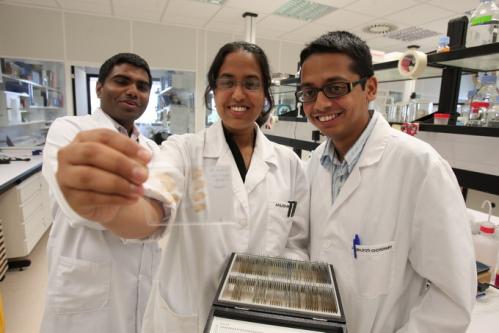

Research: Good quality independent research is a hallmark of any global university. It actively feeds into pedagogy through cutting-edge curriculum, forms the basis for business development in the corporate sector, and can also be the anchor for government policy making. Except for a handful of stand-alone research institutes, India lacks the culture of independent academic research and, here again, India could learn from the superior experience of the U.S. higher education system.

Governance: For higher education institutions to thrive and compete globally in the above three areas, India must develop a robust governance structure for this sector. Considering what aspects of the regulatory framework and accreditation system of the U.S. higher education sector make it flexible and innovative can be the most critical area where India can learn from the successes of the U.S. university system.

The creation of world-class universities and a culture of academic excellence will benefit millions of Indian students. This makes economic and strategic sense for both India and the U.S., which share common values of liberal plural democracy.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).