Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

This article is a part of India 2024: Policy Priorities for the New Government, a compendium of policy briefs from scholars at Brookings India, edited by Dhruva Jaishankar and Zehra Kazmi, which identifies & addresses some of the most pressing challenges that India is likely to face in the next five years.

India has seen a rapid expansion in the higher education sector since 2001. There has been a dramatic rise in the number of higher education institutions (HEI) and enrolment has increased four-fold. The Indian higher education system is now one of the largest in the world with 49,964 institutions. Despite the increased access to higher education in India, challenges remain: low employability of graduates, poor quality of education, and complex regulatory norms continue to plague the sector. India’s gross enrolment ratio (GER) in 2017-18 was 25.8% but it is still far from meeting the Ministry of Human Resource Development’s target of achieving 30% GER by 2020.

As the global economy is undergoing structural transformation, there will be a shift in labour market requirements. India will require workers in newer and more diverse job roles: sophisticated researchers, innovators, and knowledge workers. Institutions have failed to identify the true potential of a higher education system that provides necessary skills. Systemic issues will need to be addressed to create globally relevant and competitive institutions that can produce employable graduates.

Enhance Postgraduate Capacity

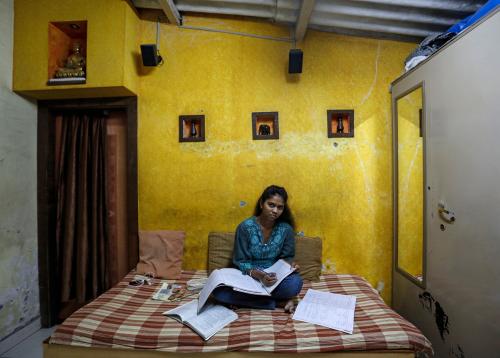

There is close to 80% enrolment in HEIs at the undergraduate level. While postgraduate enrolments have more than doubled since 2009-10, there remains a disparity in undergraduate and postgraduate enrolment due to a lack of capacity. Postgraduate education is a unique avenue to achieve specialised training and allows for improved employability. But apart from Masters of Arts, Science, and Commerce degrees, only MBA has become a popular degree due to the bright employment prospects it offers. Research degrees account for a very small proportion of enrolments, and the proportion of PhDs awarded has fallen in the last decade. Only 36.7% HEIs run postgraduate programs, and merely 3.6% run PhD programs. A direct consequence of low enrolment in postgraduate programs is the shortage of qualified teachers in the higher education system.

The government must lead the effort in expanding postgraduate capacity sufficiently. Private institutions do not find it commercially feasible to run postgraduate programs, other than in courses like management and engineering. Mandating all HEIs to have postgraduate departments in fields where there is a paucity of postgraduates and teachers can help bridge the gap. Incentivising postgraduate education and awarding fellowships in all subject areas will be significant motivation. Providing students with greater access to postgraduate education will position India well to cater to the changing requirements of the labour market by delivering a highly skilled and job-ready workforce.

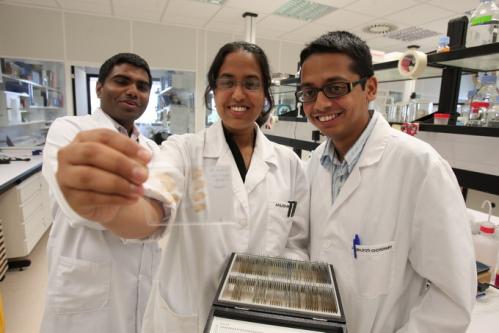

Build Research-Focused Institutions

Research in HEIs in India is not viewed as a primary and vital function. Institutions view teaching and examining masses as their core function. HEIs have failed to recognise that teaching and research are complementary and mutually supportive activities. Basic fundamental research, funded by the government, takes place in academic settings. India’s gross expenditure on research & development (GERD), as a proportion of GDP, has declined since 2001 and is now lower (0.62%) than it was in 1996 (0.65%). This decline is reflected in India’s poor research capacity as well as inadequate research output and impact when compared to countries like China.

Two decades ago, China’s GERD was lower than India’s. It has quadrupled since then. In addition to increased investment, China has built research-focused institutions by incentivising research and innovation. More than two dozen research agencies are actively involved in higher education policymaking in China; these are absent in India. Policy reforms have fostered world standards among Chinese HEIs. It is leading the way in publications, patents and has, by some measures, four of the top ten-ranking academic institutions globally. China’s transformation into a knowledge-based economy suggests that funding, primarily from the private sector, is key to producing top-class research. There are limited sustainable market solutions to support research. Applied research has to be industry-driven, for its use. Currently, Indian HEIs are poorly connected to corporate entities.

The government must facilitate university-industry linkage to transfer knowledge from academic to applied settings. Corporate endowments can help build sound infrastructure for research in HEIs and set up R&D facilities on campuses, which, at present, are rare. Support extended to research through Corporate Social Responsibility should be formalised under CSR rules. India should encourage philanthropic contribution for scholarly research, as China has.

Relax Complex Regulatory Norms

For far too long, India has subjected itself to a challenging regulatory environment with a centralised control mechanism. Multiple agencies (state governments, professional councils, affiliating universities, etc.), their overlapping functions, and stringent rules have resulted in fragmentation of the higher education system. The University Grants Commission (UGC) has not been able to successfully monitor the quality of HEIs and implement standards. Limited capacity of accreditation agencies to assess all HEIs has resulted in failure to recognise and reward high performing institutions. Further, an ‘affiliation’ setup between colleges and universities has weakened the potential of institutions that could have otherwise excelled.

While recent reforms such as granting graded autonomy to HEIs have promoted academic freedom, more must be done to ease the regulatory environment. A UGC overhaul is expected soon. The new apex regulator should solely aim to promote quality in academic instruction. Accreditation, by empanelled quality assurance agencies with specialised focus areas, should be made mandatory for all HEIs. The move will also improve accreditation coverage. Then, the next step should be to ensure that assessments are made actionable. Decisions of recognition, autonomy, and affiliation can be linked to accreditation results. Grant disbursal to HEIs should be handled independently, on the basis of merit. This will ensure accountability among regulators and accreditation bodies and transparency of the funders.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

India 2024: A highly educated India

May 17, 2019