Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

Over the past decade, college tuition fees in the United States have skyrocketed, making it extremely difficult for average Americans to invest in higher education. Within the same time frame, the country has fallen from being ranked number one in college degree attainment to number 12 globally. The rising costs of higher education has translated into a widening gap between the wealthiest and the poorest sections of American society. This is a stark indication of growing inequality of income and opportunity within the U.S. economy. Even among those who go on to complete a college degree, debt is a serious concern. Student loan debt has now surpassed credit card debt for the first time in the country. In response to this growing problem, President Barack Obama expanded federal support to help more students afford college education, while making calls to tackle rising college costs. He also set a new goal for the country: that by 2020, the United States would once again have the highest proportion of college graduates in the world.

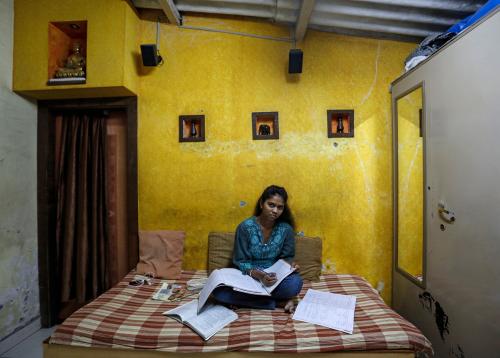

In comparison, Indian students are faced with nearly infinite costs of higher education given the severe shortage of quality institutions in the country. These get reflected through unreasonable entrance requirements where students need to score 100 percent to get admission to some of the top colleges, and a very significant number of students opt to study abroad at much higher costs. The excess demand for higher education in India, with limited supply of quality institutions, has led to the proliferation of many dubious illegal institutions across the country. Compared to China, access to higher education in India looks dismal. In 2000, the gross enrolment ratio (which measures the number of individuals going to college as a percentage of college-age population) was 8 percent in China and 10 percent in India. By 2008, Chinese higher education reforms ensured that their gross enrolment ratio rose to 23 percent while in India this rise was only marginal to 13 percent. This reflects the slow pace of growth of the Indian higher education sector. The problem takes on catastrophic proportion when viewed from the lens of India’s demographic structure. Lack of access to higher education over the next two decades could quickly transform India’s demographic dividend into a demographic disaster.

India and the United States already have several areas of collaboration in the higher education sector that could mutually benefit the two liberal democracies. In September 2014, marking their first bilateral summit, Prime Minister Modi and President Obama committed themselves to a new mantra for the India-U.S. relationship, “Chalein Saath Saath: Forward Together We Go.” The joint declaration, endorsing the first vision statement for the strategic partnership between the two countries in various sectors, including higher education. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has been tasked with providing a range of high level analytical, diagnostic, and organizational development services to support the efforts of India’s Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD). This includes faculty development, exchange programs, and partnerships with leading U.S. higher education institutions. The U.S. government re-launched the Passport to India initiative to work with the private sector to increase internship opportunities, service learning, and study abroad opportunities in India. This initiative is also about to launch a massive open online course (MOOC) for American students who are keen to learn more about Indian opportunities.

Beyond these developments, the following steps can still be taken:

- The government of India proposed several new ideas for faculty exchange through its Global Initiative of Academic Networks (GIAN) program. The MHRD will create a channel for U.S. professors in science, technology, and engineering to teach in Indian academic and research institutions on short term exchanges. This would be a mutually beneficial collaboration if it were to allow faculty members from U.S. universities to spend six months of their sabbatical year in India. Indian academic institutions would gain tremendously from such visits, and such short term appointments should be facilitated and strongly advertised.

- Employability is a key concern and several efforts have been made to encourage new certification programs, knowledge sharing, and public-private partnerships between the two countries. Obama has put special emphasis on community colleges given their critical role as a gateway to economic opportunity for poor and middle class Americans. There are significant potential gains to be made through collaboration between U.S. community colleges collaborating and Indian institutions, which can adopt models of best practices in skill development. There is already an agreement between the All Indian Council of Technical Education (AICTE) and the American Association of Community College for curriculum development and adopting industry demands to train the future workforce.

- There are many new ideas that are being jointly explored between the two countries. Most of these ideas run the risk of remaining token measures until India brings about fundamental changes to the regulatory framework of its higher education sector. Beyond good intentions, India will have to completely transform bodies such as the University Grants Commission (UGC), AICTE and the Medical Council of India (MCI) by making them more transparent, accountable and thereby more competent to regulate the higher education sector in the country.

From India’s perspective, the overall objective of such bilateral collaboration has to be improvements in access to quality higher education for students and a greater capacity for research and teaching among faculty. Both are essential if India is to realise its promise of a demographic dividend.

This memo is part of the Brookings India publication, India-U.S Relations in Transition. The views are those of the author(s). Brookings India does not hold any institutional views.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edIndia-US relations: Higher education

June 4, 2016