A recent New Yorker article highlighting the likelihood of a massive earthquake near Seattle has reverberated across the country, from seismologists to policymakers to business leaders. Similar to the highly destructive earthquake and tsunami off the coast of Japan in 2011, it appears to be only a matter of time before a more serious disaster strikes the Pacific Northwest, displacing thousands of residents and leading to a host of infrastructure failures.

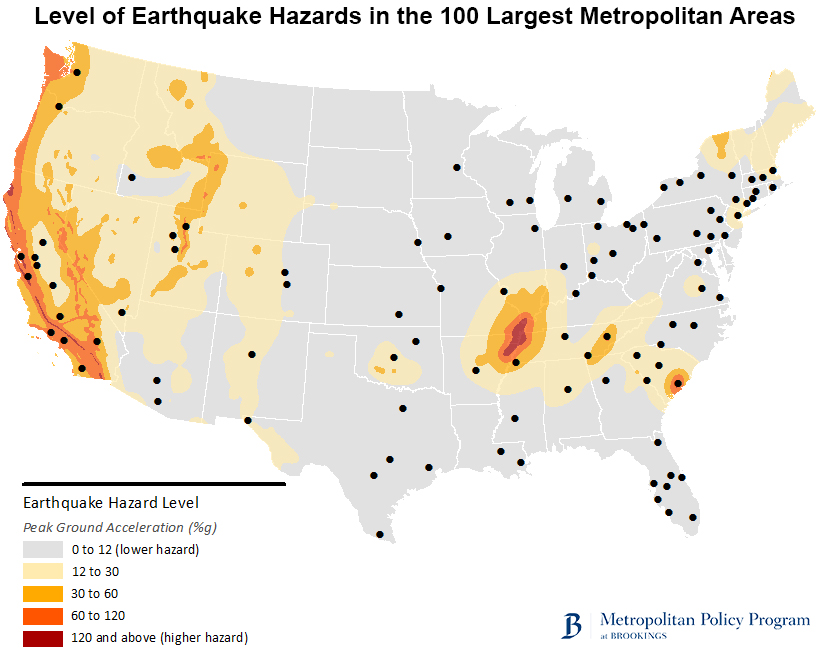

Seattle is not the only area dealing with this risk, though, and the need for a more resilient, proactive approach to address its various infrastructure concerns. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the potential for a big earthquake touches dozens of the country’s largest metro areas, with some of the most severe hazards stretching far beyond the West Coast. Measured in terms of peak ground acceleration—or the relative increase in shaking during an earthquake—these hazards pose a threat to numerous water systems, electrical grids, and other structures, the probability of which is tracked over many decades in different regions.

Source: Brookings analysis of USGS data

Note: As noted by USGS, colors on this map show the levels of horizontal shaking that have a 2 percent chance of being exceeded in a 50-year period. Shaking is expressed as a percentage of g, which refers to the acceleration of an object due to gravity. Values may vary within individual metro areas.

Expressed as a percentage of gravity (% g)— with values ranging from 0% g (lower hazards) to more than 160% g (higher hazards)—the most destructive shaking is not surprisingly linked to California metro areas like Los Angeles (160% g), Riverside (160), and San Jose (160), all resting along the San Andreas Fault. By comparison, Seattle (60) and Portland (50) face relatively lower hazards, despite their location in the Cascadia Subduction Zone. Farther east, however, noticeably higher hazards appear near Memphis (120) and Charleston (120), which have historically experienced some major earthquakes. In total, 35 of the country’s 100 largest metro areas have a hazard level above 20% g, and 18 areas exceed 60% g.

Given the widespread risk and severity of these hazards, regions will need to develop stronger plans and investments to prepare for earthquakes. Installing more extensive warning systems and seismic upgrades to buildings, for instance, represent a couple ways regions can better safeguard their populations and infrastructure assets. While places like Seattle will continue to face higher earthquake risks, they are certainly not alone in addressing them.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Seattle isn’t the only metro bracing for another big earthquake

July 16, 2015