As the generative AI goldrush continues, entrepreneurs, investors, and tech thinkers are forecasting its winners. Some believe that for once, small and geographically diverse firms and startups—rather than Big Tech and its usual coastal hubs—will prevail.

And indeed, a new generation of AI applications powered by large language models (LLMs) is rapidly spreading across the internet, hastened by licensing deals with firms such as OpenAI and the use of open-source software. For example, Meta has long open-sourced its leading algorithms for any developer to freely use, including its latest generative AI system, known as LLaMa 2. For its part, the UK research firm Google DeepMind has also historically open-sourced many of its leading algorithms for coders to download and build on at will.

All of which has informed a compelling narrative. As Cade Metz of The New York Times recently summed up, “Many in the field believe this kind of freely available software will allow anyone to compete.”

And yet, despite this pretty picture of tech inclusion, work at Brookings and elsewhere suggests that the winner-take-most dynamics of digital technologies—as well as the mechanics of AI itself—cut against such decentralization, at least among cities. What’s more, our latest research now confirms that in the past year, well over half of all job postings in generative AI have clustered in just 10 metro areas—many of which are the same large coastal hubs that AI optimists believe the technology should diffuse out of.

So, rather than democratizing tech, generative AI could well further concentrate AI activity in the absence of deliberate intervention

Tech innovation tends to concentrate in key hubs, and AI is following the same path

As we detailed in our July report on building AI cities, digital industries tend to concentrate in just a few key hubs—notably, the Bay Area—for specific reasons. These include the innovation benefits of local clusters, the need for deep pools of specialized talent, and the benefits of “winner-take-most” network effects playing out across huge platforms.

To be sure, a degree of employment diffusion occurs over time as more middle-wage work in a field begins to spread to new regions. But even so, Stanford University economist Nicholas Bloom and his team have shown that over the past 20 years, most disruptive technologies have remained highly concentrated in their core locations—conferring long-lasting advantages on these “pioneer” locations.

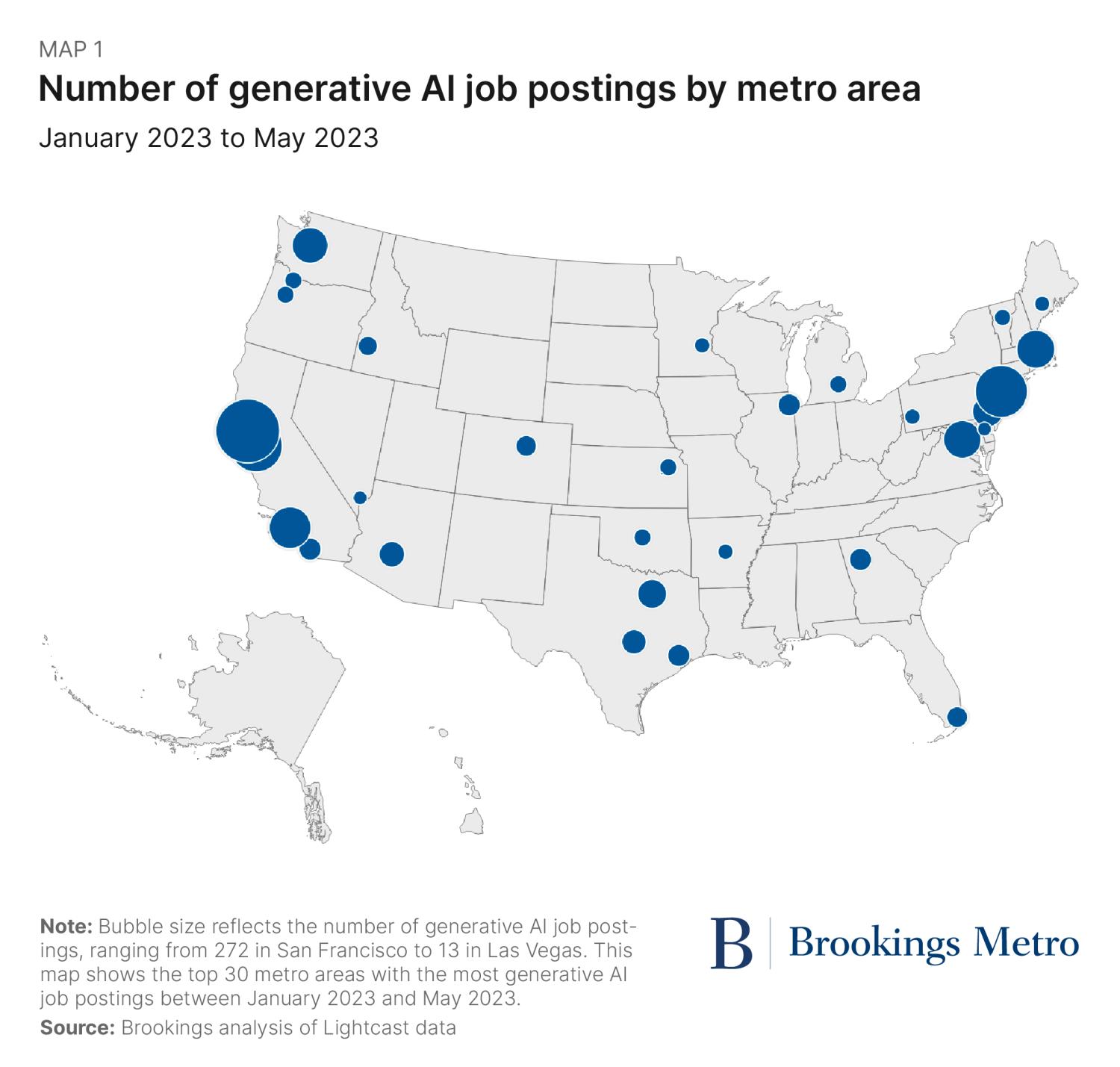

Nor does the prognosis seem hugely different for AI, although we are still in the technology’s early days. Brookings research from 2021 showed that the Bay Area and 13 “early adopter” metro areas accounted for over half of the nation’s AI activity in federal contracting, conference papers, patents, job postings, job profiles, and startups. More recently, our July report found that nearly half of job postings for generative AI positions over the prior the 11 months were concentrated in just six large coastal metro areas: San Francisco, San Jose, Calif., New York, Los Angeles, Boston, and Seattle.

Now, our new analysis finds AI postings concentrating even further.

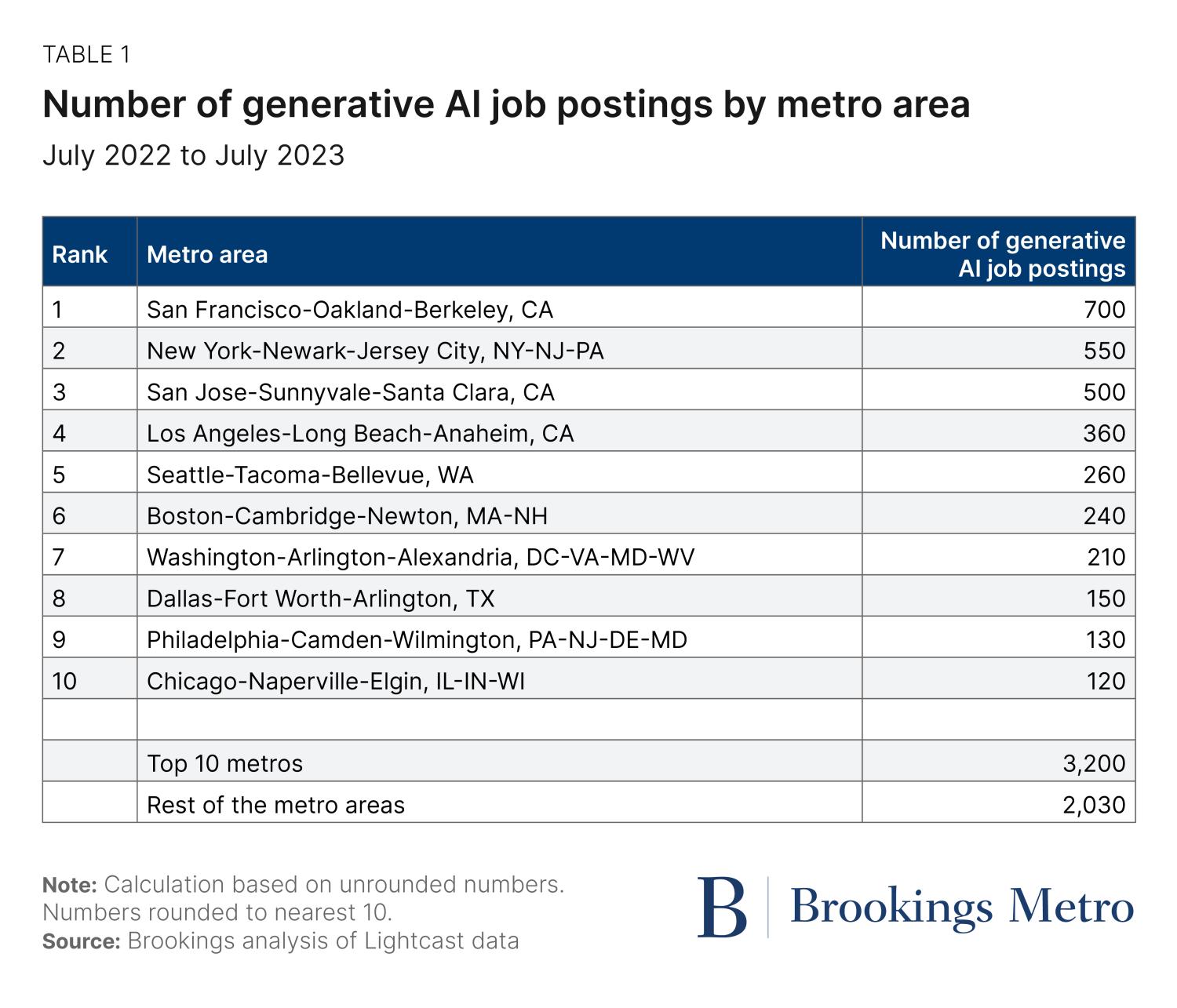

Nationwide, over 60% of generative AI jobs posted in the year ending in July 2023 were clustered in just 10 metro areas. Nearly one-quarter of those postings were in the Bay Area, with the others concentrated a short list of big “superstar” cities.

The particulars of AI could lead to even further geographic concentration

The new job posting numbers make the generative AI story—and the AI story more broadly—look a lot like the social media story, the earlier internet boom, and the PC boom before that in regards to their geographic concentration. As the latest digital technology, AI appears to be developing along the same highly clustered path of previous digital services, driven by its need for deep pools of preexisting expertise and talent.

What’s more, key features of today’s AI models could well intensify their tendency to concentrate. To be sure, projected accessibility and affordability gains in computing costs and the relatively modest costs of fine-tuning and training new versions of preexisting “base” or “foundation” models suggest that more AI work could soon be done anywhere, allowing for greater industry decentralization into more places.

But even so, policymakers and technologists need to take into account the costs, technical talent, and computing hurdles that tend to locate the building and training of foundation models in frontier hubs. These—combined with first-mover advantages of all sorts—are serving to centralize AI development and anchor it in core management and design hubs dominated by the most well-resourced companies and clusters.

Which is why it seems likely that AI—notwithstanding its promise for driving productivity surges in firms, exciting new use cases in new areas, and economic benefits for local economies—will continue to be dominated by the same usual regions.

Key investments can help AI activity spread to more places

So, what should be done? Looking forward, the nation, states, and industry will likely need to actively intervene to promote a more inclusive AI geography.

Central to such actions should be place-oriented measures to improve the availability of key inputs to AI innovation and commercial adoption in scores of promising regions, not just a few. To that end, Brookings’s July report mentions a variety of potential federal, state, and local actions—a number of which are already being piloted, and worth reiterating here.

To distribute AI research and development more widely, the nation should expand the National Science Foundation’s National Artificial Intelligence Research Institutes program, through which 19 universities are pursuing diverse, locally relevant research agendas that serve nearly 40 states. Since universities provide a widely distributed network of hubs for technical growth, such investments are critical.

In addition, the federal government should establish and build out the proposed National AI Research Resource (NAIRR), which would democratize access to an array of essential data and computational resources. For example, NAIRR could be used to train foundation models for public use, thereby reducing the prohibitive costs for such work in non-superstar hubs.

For that matter, states and regions—in partnership with federal agencies—urgently need to expand digital education and training efforts. These should have a special focus on ensuring underrepresented groups can access AI skills pathways in places where AI activity is emerging.

States also have a special opportunity now to leverage multiple “place-based” industrial policy programs in service of turning emergent local AI activity into true growth clusters. As it happens, AI is designated as a “key industry” by both the Department of Defense and the hallmark CHIPS and Science Act, meaning that AI development in new places is a stated priority of the U.S. government. States and regions should explore new ways to access and deploy resources for building up local AI ecosystems as they emerge.

Decentralization of AI activity is possible—if we try for it

In sum, it could be that AI’s growth will be different from that of every preceding digital technology. Maybe a surge of open-source development and cheaper, more accessible cloud-based computation really will free AI activity from the concentrated resources, talent, and research institutions of the first-mover hubs.

But as this new data on generative AI job postings shows, the winner-take-most dynamics of the digital sector’s past may also be prologue for AI. In which case—and really, in either case—the nation, states, and localities must act now to broaden the reach of AI’s development and secure its benefits for more people in more places.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).