Dramatic advances in generative artificial intelligence (AI) have touched off intense debates about who will “win” the rush to deploy these technologies. Much has been written about AI’s potential to displace millions of workers, but leaders across the country also see the emerging technology as an opportunity to boost the productivity and dynamism of their regional economies.

On one hand, generative AI has suddenly made artificial intelligence’s status as the next great “general purpose technology” much more palpable, even to local business people, as Microsoft and Google integrate AI chatbots such as ChatGPT and Bard into their search engines. At the same time, the relative scarcity of AI research centers and companies—and Big Tech’s domination of those that do exist—is raising questions about the opportunity structure and geography of the AI revolution, if left to its own devices.

The generative AI boom may well democratize the broader AI industry beyond Big Tech and its core development hubs in San Francisco and Seattle—but it could also sustain or reinforce the industry’s concentrated geography.

“AI is increasingly defined by the actions of a small set of private sector actors, rather than a broader range of societal actors,” observed Stanford University’s Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence in a report earlier this year. Such dynamics are reinforcing those that have defined digitalization since the 1980s. They are also likely to ensure that most AI development activity (and hiring) remains highly concentrated in a short list of “superstar” metro areas and early adopter hubs, as Brookings described in a 2021 report. In that report, Brookings documented the technical and business dominance of early-stage AI development centers such as San Francisco, San Jose, Calif., Seattle, and Boston.

The effective universal deployment of generative AI may well widen the geography of the overall AI industry—but then again, it might instead harden the dominance of the industry’s core hubs, especially when it comes to research and development. High and persistent levels of industry concentration could have negative implications for economic opportunity, regional growth, and the development of an AI sector that serves a broad consumer base with varied products and services.

All of which suggests that if generative AI is to boost prosperity in more places around the country, it will likely require a degree of intentional investment—most notably, from the federal government—in new regions.

This is the subject of the current report. A companion to the earlier Brookings paper that warned about the uneven geography of AI activity, the discussion here reviews the AI location problem and highlights key federal, state, and local policy moves that could counter it.

The report begins by reviewing the intensely concentrated nature of the overall AI industry (as opposed to the recent boom in generative AI) and suggesting the need to widen the sector to ensure broader participation. (At a few points the report touches on the specific growth trajectory of generative AI applications.) After that, the report recommends an array of federal, state, and local actions that could promote more even geographic development as the industry enters a new growth stage powered by generative AI. Ultimately, the report suggests that policymakers now have an opportunity to bring about more geographically inclusive development for one of the most important innovations of our time.

Advanced economies have increasingly recognized that the geography of where jobs and businesses related to emerging technologies locate has become a challenge. The artificial intelligence industry—and potentially its sub-category of generative AI—stands out as a prime example of this, given that it encompasses powerfully disruptive digital technologies.

There is no doubt that the emergence of powerful technologies tends to have significant spatial ramifications for nations. This is particularly true of digital technologies, where innovation tends to be concentrated but products are widely used, given network effects across massive platforms.

In the U.S., recent waves of tech innovation and adoption have greatly altered the nation’s economic landscape. These waves have brought both the diffusion of new technologies into new regions (with local economic benefits), but also intense clustering of jobs and businesses related to them, which has contributed to vast inequality among regional economies.

One string of research has found that once new technologies mature, they begin to spread out geographically. These effects may be gradual, but they are real and beneficial. With that said, the invention, development, and scale-up of disruptive technologies has also been recognized as geographically skewed.

Economist Enrico Moretti has shown that the U.S. high-tech sector has increasingly concentrated in a small number of expensive, mostly coastal cities, with the top 10 cities for computer science, semiconductors, and biology and chemistry accounting for 70%, 79%, and 59% of those inventors, respectively. Economist Nicholas Bloom and his colleagues studied 29 disruptive technologies from the last 20 years and found that the distribution of those jobs remained highly concentrated, with long-lasting advantages for the “pioneer” locations.

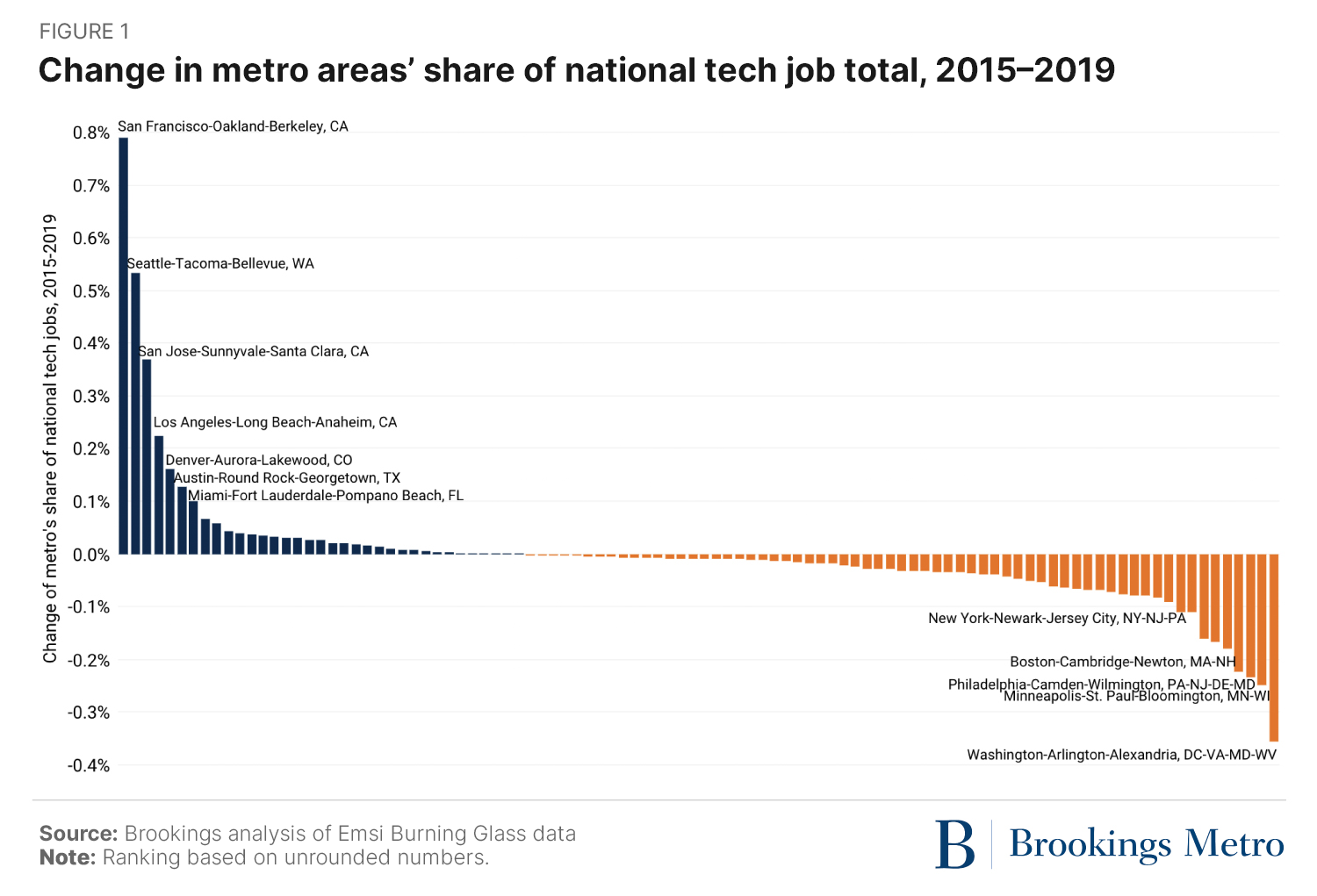

And Brookings Metro recently described a similar “winner-take-most” dynamic in six digital service industries, where the concentration of employment in a short list of “superstar” metro areas has been increasing over the last decade.

Despite the known benefits of such industry clustering, the uneven geography of tech is not always benign. Most notably, certain aspects of clustering—based on tech-inherent influences such as first-mover advantages, agglomeration dynamics, and the network effects produced by tech platforms—threaten the balance of the economy.

As an innovation matter, the nation’s hyper-concentrated tech geography may be narrowing the range of possible tech advancements and creating harmful imbalances among firms, local ecosystems, and the resources they command. And as an economic development issue, such imbalances tend to create large pools of high-skill workers in some areas while other areas suffer a “brain drain” that leaves lower-skill workers behind.

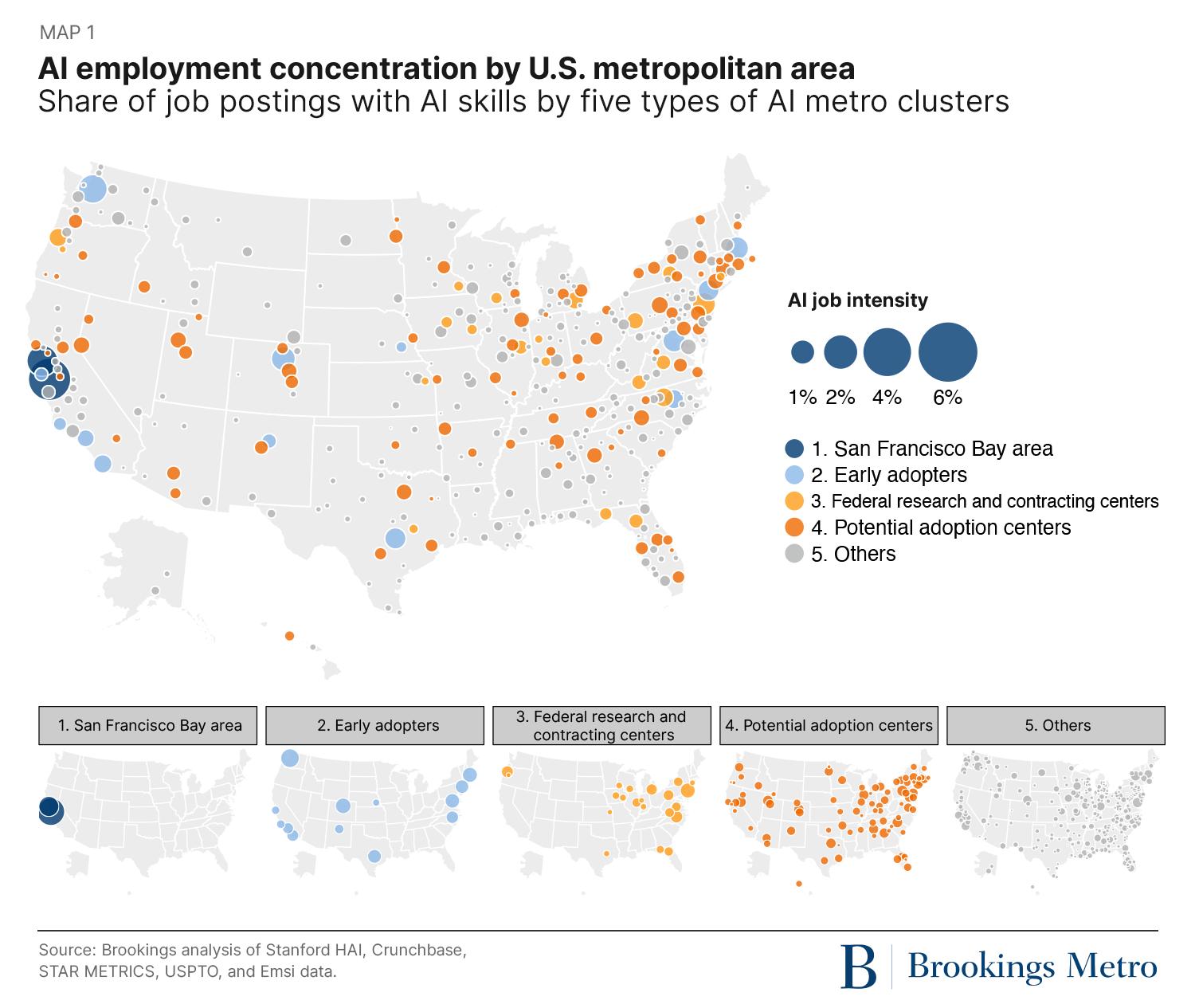

Artificial intelligence, in broad form, epitomizes the frequent geographic unevenness of emerging technology build-out. Nicholas Bloom’s research tracked machine learning and AI as one of its 29 disruptive technologies, and depicted both as seeing a gradual diffusion of lower-skill jobs yet a persistent centralization of the highest-value work. Brookings Metro’s 2021 report showed an even more skewed development pattern. Employing a cluster analysis of metro area data covering seven measures of AI research and commercialization across 384 metro areas, we found that AI activity in the U.S. is highly concentrated in a short list of “superstar” hubs and “early adopter” centers.

Among these hubs, San Francisco and San Jose, Calif. alone accounted for about one-quarter of AI conference papers, patents, and companies in 2021. These Bay Area metro areas also boasted about four times as many AI companies, job postings, and job profiles as the average values of the next tier of 13 early adopter metro areas. Central to their success are the world’s two top universities in AI research (Stanford and the University of California, Berkeley) as well as many of the world’s leading investors in AI research and development, including Alphabet, Facebook, Salesforce, and NVIDIA.

Add in the 13 early adopter metro areas (which range from New York and Boston to Seattle, Austin, Texas, and Raleigh, N.C.), and the top 15 AI metro areas encompass about two-thirds of the nation’s AI assets and capabilities.

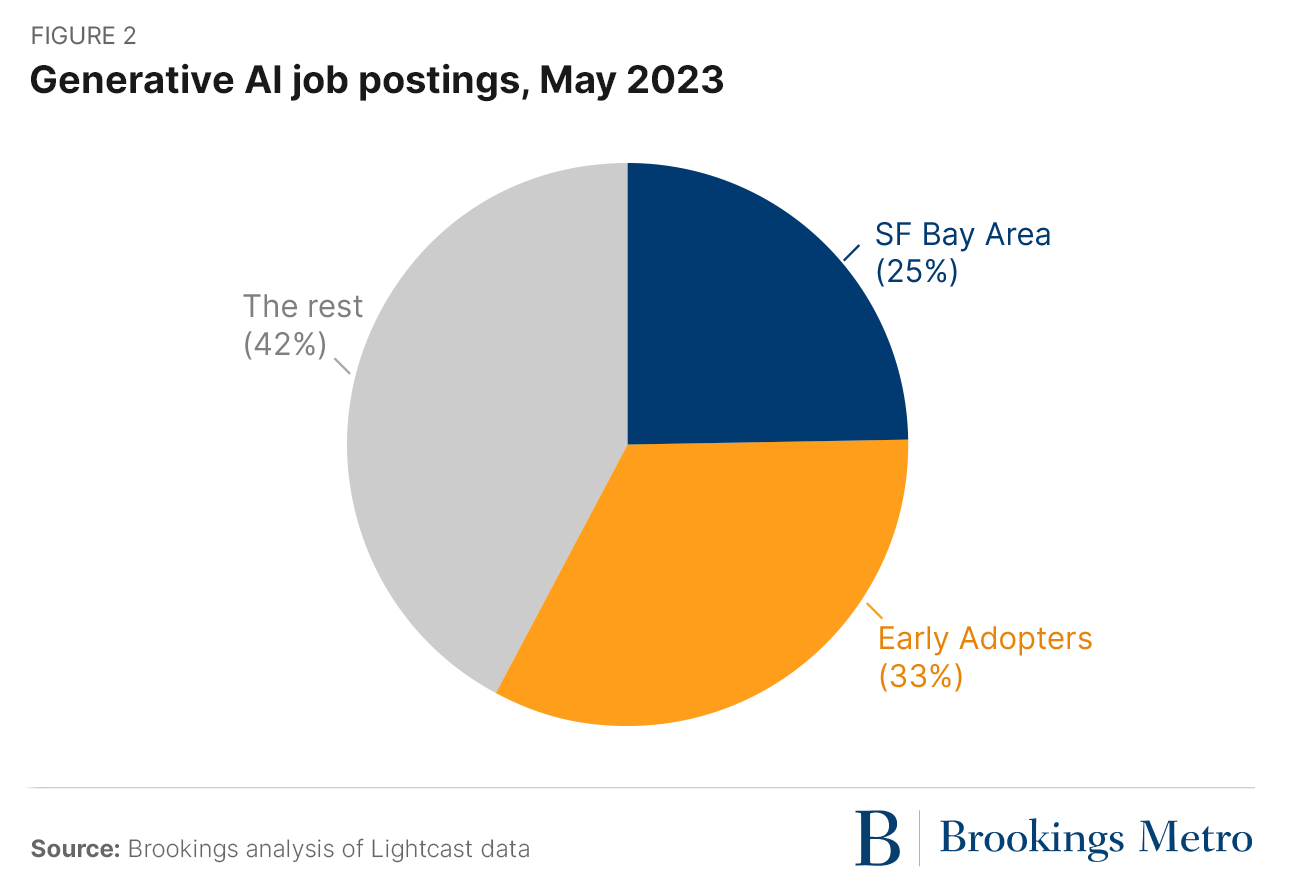

As to generative AI, data limitations associated with its recentness restrict what can be said. However, at least one signal—January 2023 to May 2023 job postings data from Lightcast—points to the kind of highly concentrated job market expected for a newly emergent application. In May 2023, nearly 60% of new generative AI jobs were posted in the Bay Area or one of the 13 early adopter metro areas, including Seattle, home to Microsoft. And over the preceding 10 months, just six metro areas (San Francisco, San Jose, New York, Los Angeles, Boston, and Seattle) accounted for nearly half (47%) of the nation’s generative AI job postings in the Brookings database.

To be sure, the broad diffusion of generative AI applications (including through major search engines and app stores) may ensure that at least part of the generative AI economy spreads widely. Open-source distribution and widespread licensing of large language models may also decentralize the industry. But the wide distribution of a digital technology does not necessarily entail the wide distribution of its associated innovation, job creation, and executive leadership.

Early indications suggest that generative AI’s most advanced core research and development activities will likely remain concentrated in a few top centers of general and generative AI work. Such trends depict the geographic side of nation’s AI challenge as the generative AI era scales up. As a matter of economic development, current trends suggest that “relatively few places will drive the bulk of early-stage AI-related development,” as Brookings’s Alan Berube and Max Bouchet wrote about Louisville, Ky.’s situation prior to the ChatGPT moment. That narrowness may limit many places’ AI prospects, as the AI “rich” only get richer.

More broadly, the extreme clustering of AI activities in a few hubs anchored by elite universities and major corporations has ramifications for the prosperity and health of the nation. Such clustering and the parallel emergence of AI “deserts” could limit generative AI’s variety, accessibility, and potential to improve the quality of life in many communities.

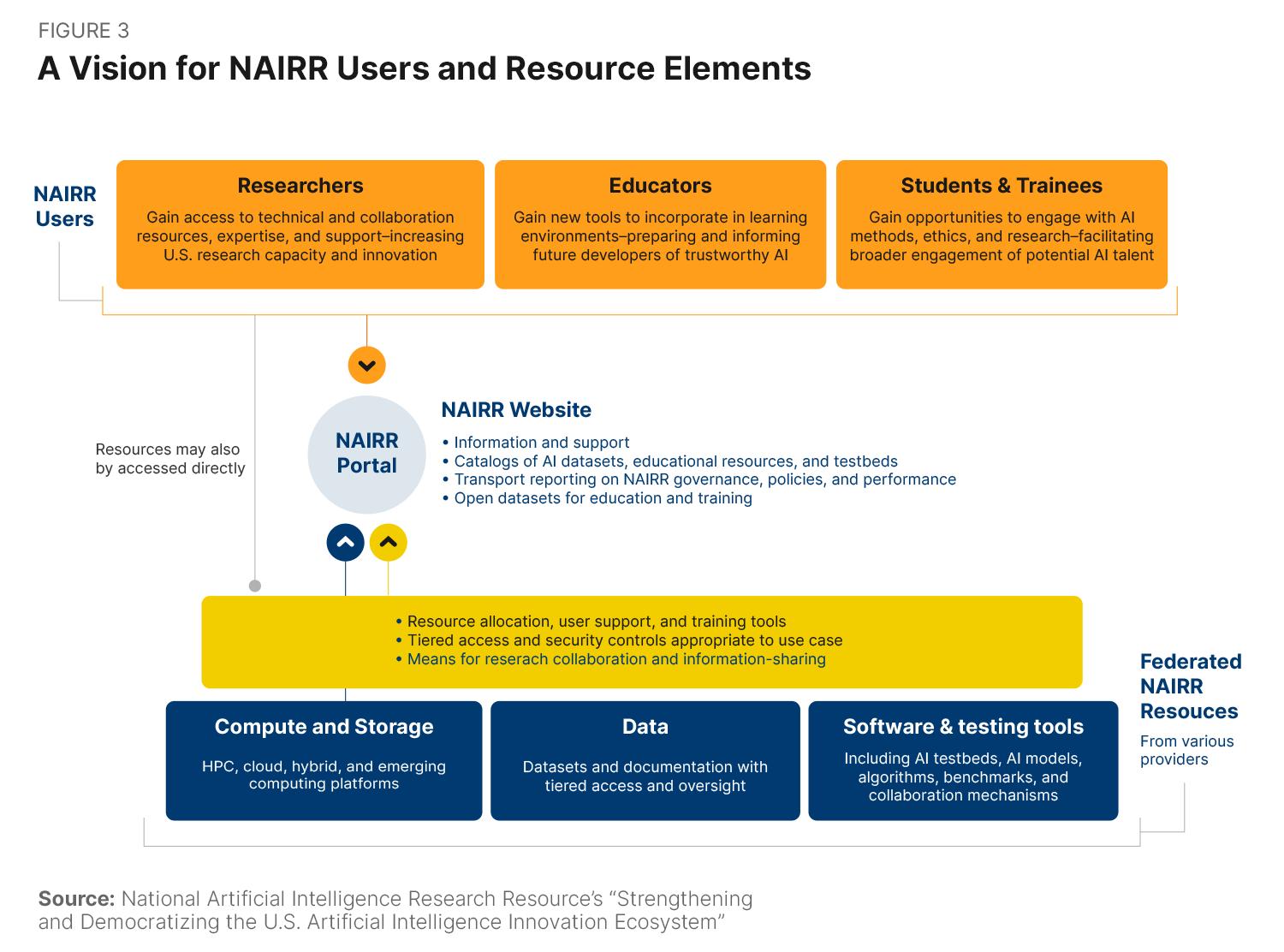

As Sethuraman Panchanathan of the National Science Foundation (NSF) and Alondra Nelson of the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) wrote last year in a National AI Research Resource (NAIRR) Task Force report, “pathways into AI research are too often accessible to a limited few. Much of today’s cutting-edge AI research relies on access to large volumes of data and advanced computational power, which are often unavailable to many researchers beyond those at large technology companies and well-resourced universities. This lack of access can lead to communities—particularly those that have long been underrepresented or underserved—being left out of the AI research and development process.”

Add in the “winner-take-most” dynamic of digital economies, and it’s likely that the growing geographical divergence of the AI sector could easily become entrenched, even as the generative AI gold rush holds out potential opportunity for new firms in new places.

The increasing geographic concentration of AI raises the question of whether policy can or should be marshaled to counter it and promote more broadly shared benefits.

Not everyone agrees that the nation’s narrow AI geography merits a policy response. Some argue that such imbalances have served the tech sector well and might even be the optimal, market-ordained configuration for maximizing innovation in AI, given the power of innovation clusters. Others contend that imbalances in the AI sector will at least partially self-correct, and broader diffusion trends will take over with time. Nicholas Bloom’s research on disruptive technologies reinforces that possibility—at least when it comes to lower-quality jobs in maturing sectors.

However, good reasons exist to doubt such laissez-faire views and favor interventions to counter excessive AI divergence. To start, the negative effects of excessive local tech industry concentration are increasingly well recognized. Economists and policymakers are increasingly worried about the side effects of extreme industry unevenness in the economy, including such effects as spiraling housing prices in superstar metro areas as well as lost talent in the communities left behind.

Today, those economists and policymakers are also more willing to consider intentional policy interventions to offset excessive concentrations of tech-based development. Scholarship is increasingly highlighting the successes of “place-based industrial policy”—efforts to adjust the quality and geography of advanced-economy scale-up and growth. Detailed by Shawn Kantor and Alexander Whalley, a case in point is federal technology investment during the Space Race, which delivered social rates of return on public research and development above 20%, while permanently altering and improving the geography of high-tech economic activity in the U.S.

Given these insights, the nation and its states should consider concerted actions to broaden the emerging AI map as the technology grows in significance.

The rationale for action is compelling. The dynamism of the U.S. industrial base depends on increased innovation in more regions, to which AI will be central. Doing nothing will likely leave AI to concentrate even more, and with more concentration will come increased marginalization of the “rest” of the nation. That means continued isolation of diverse regions, firms, and people from the waves of advancement likely coming through generative AI and other industries’ use of it, such as in finance, health, transportation, education, food production, and environmental sustainability.

In light of that, the nation should move to intentionally promote diffusion of AI activities into new places and counter the winner-take-most geography of a critical future industry. Central to such actions should be place-oriented measures to improve the availability of key inputs to AI innovation and commercial adoption in scores of promising regions. Such measures should move to:

- Expand public sector research in widely distributed institutions as a counter to the increasing tilt of research toward Big Tech firms and major universities in a short list of superstar hubs.

- Democratize access to computing resources and large datasets in order to support advances outside the superstar orbit.

- Invest in the talent that will drive dynamic ecosystems in new places.

- Promote the emergence of vibrant AI development ecosystems in more regions.

In terms of taking the lead on these priorities, the federal government—with its scope and cross-border jurisdiction—will need to play the largest role in spreading out AI development and employment. But states, regions, and local actors will also need to contribute to shaping regional strategies, mobilizing stakeholders, and delivering programs.

Federal leadership will be essential to push against excessive AI sector concentration. The power of digital “superstar” dynamics and the vastness of the U.S. landmass mean that only the federal government has the reach and resources to broaden AI’s geography. Fortunately, the national government has already begun to take steps to counter the sector’s winner-take-most tendencies.

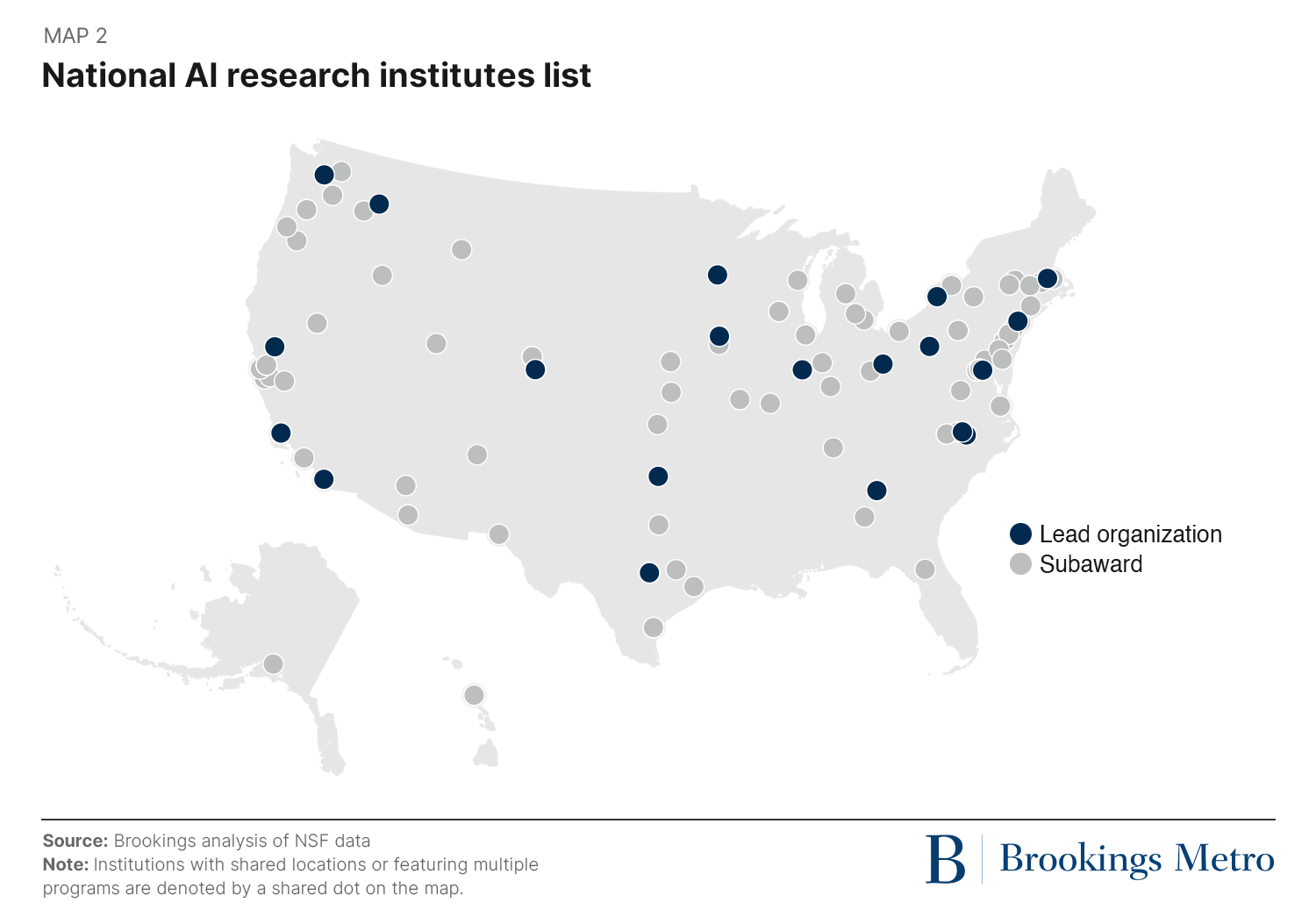

Since 2020, the NSF has been building up a distributed network of National Artificial Intelligence Research Institutes, based at universities all across the country. So far, a combined investment of nearly $500 million over five years has established 19 of these institutes, with links to 37 states.

In addition, a National AI Research Resource (NAIRR) Task Force began working in 2021 on a major roadmap for “democratizing” access to AI development resources (including computation resources), with special attention to regional and demographic disparities. The task force released its implementation plan in January 2023. Relatedly, most of these programs highlight the provision of STEM education and workforce development as key supports of AI talent development.

Finally, the $80 billion surge of “place-based” industrial policy measures advanced by the 117th Congress contains multiple investment programs that explicitly seek to ameliorate the nation’s hyper-concentrated AI geography. For example, the Notice of Funding Opportunity for the Economic Development Administration’s (EDA) Build Back Better Regional Challenge (BBBRC)—which is aimed at bolstering innovation clusters in new places—explicitly called out the establishment of an “AI corridor” in a new region as a potential proposal for a winning grant. Ultimately, the agency named two AI initiatives—from the Georgia AI Manufacturing coalition and the Louisville Healthcare CEO Council—as finalists, and provided more than $65 million to the former as a winner (more information later in the report).

Likewise, the announcement of the NSF’s Regional Innovation Engines competition mentioned AI in declaring the prioritization of regions that “do not have well-established innovation ecosystems.” More broadly, the CHIPS and Science Act names AI as a “national-security critical technology” suitable for the focus of some of its 20 authorized Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs aimed at “increasing the participation of underrepresented populations and geographies in innovation.”

Yet much more needs to be done. In many cases, the nation’s solid initial policy gestures need to be fully funded, built out, and in time expanded if the nation is to ensure more geographic participation in its highly concentrated AI sector. Necessary steps to this include:

Expand and better distribute research and development. Despite recent increases in the federal AI R&D budget, both its top-line totals and geographic distribution need to be increased. FY 2023 research appropriations in AI appear to have fallen far short of hopes in a year of major industrial policy investments, necessitating renewed action in the current Congress and beyond.

This necessity reflects the fact that in 2021, the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence (NSCAI)—an independent commission Congress established to review U.S. investment needs—recommended that the nation annually double its investments in nondefense AI R&D, which would increase spending from $1 billion in FY 2020 to $32 billion in FY 2026. Such a trajectory would have required FY 2023 funding to reach $4 billion—a figure it fell far short of. Now, Congress needs to make up for lost ground by surging AI R&D investments to $8 billion in FY 2024.

For its part, the NSF should keep building out its important National Artificial Intelligence Research Institutes program and related initiatives for strengthening AI activities in new geographies. This reflects the fact that some of the most compelling new AI use cases will likely arise out of existing industry clusters building out new applications in unheralded sectors such as agriculture, transportation, and logistics. Decentralized research investments could rapidly accelerate serious AI development in new places and industry spaces. For that reason, the NSF institutes are inordinately important, and merit expansion. Already the agency is on track to launch seven more institutes in 2023, and it recently announced the ExpandAI program—a specially targeted awards opportunity focused on capacity-building and partnerships at minority serving institutions (MSIs). With about $500 million currently flowing into these geographically oriented initiatives over a five-year period, one can reasonably envision such efforts doubling in size in the next half-decade, given their focus on addressing a core aspect of the nation’s AI geography problem.

Channeling R&D into new regions: The National Artificial Intelligence Research Institutes

The NSF’s National Artificial Intelligence Research Institutes program exemplifies how smart federal investment in support of national goals can engage local institutions in promoting AI activity in new locations. The program seeks to build a broad research network across the nation by leveraging the capacities of universities in new places and launching new AI research institutes. Currently, 19 lead institutes—with funding running at $4 million to $5 million annually for four or five years—are pursuing topics ranging from intelligent agendas and climate-smart agriculture and forestry to AI-augmented education and trustworthy AI. As such, the new hubs—which are situated within academic institutions and often rely on collaboration with industry and government—are playing a compelling role in building up new talent pools across the country, even as they develop new AI applications to serve local use cases. Another seven institutes will soon fill in more blank areas on the map, and the NSF plans to multiply their impact by using the institute ecosystem to enhance capacity at underserved universities through its new ExpandAI program. In these ways the two programs will interact to significantly broaden participation in AI research, education, and workforce development.

Prioritize inclusive data and computation. In addition, the federal government should establish and build out the proposed National AI Research Resource (NAIRR), which would democratize access to an array of essential computational and data resources, testbeds, software and testing tools, and user-support services. Currently, access to the expensive computational and data resources that fuel much of today’s AI remains concentrated in a short list of private sector firms, major universities, and “superstar” tech hubs. The result is what the NAIRR Task Force calls a “disparity in availability of AI research resources [that] affects the quality and character of the U.S. AI innovation ecosystem.”

Given that, NAIRR should be established with a special focus on increasing access to critical computation resources and datasets in new communities. Such resources would be designed to make high-performance computing systems, cloud arrays, open and protected datasets, and testing and training resources more broadly available. Such availability could be specifically focused on increasing both demographic and geographic access to AI research resources. In that sense, NAIRR should be implemented with a special mission of lowering the barriers to participation in the most dynamic AI research ecosystems for both racially and spatially underrepresented AI researchers. In that vein, NAIRR’s estimated $2.6 billion cost over an initial six-year period appears quite modest for a potentially transformative step toward improved access to core AI research platforms.

Invest in talent. A federal push to democratize the demography and geography of the nation’s AI economy will also require moves to engage, educate, and upskill diverse and far-flung U.S. talent. Currently, the hyper-concentration of AI computational and data resources—combined with the concentration of associated regional economic activity in only a few places—limits the participation of underserved people and places in AI development. Given that, communities frequently lack sufficient representation and skills pathways to engage in the field.

Accordingly, the nation should multiply efforts to build a diverse and widely distributed AI workforce. Employing the same urgency needed to build regional AI ecosystems, Congress should fully fund the Regional Innovation Engines and Regional Tech Hubs programs, which are orientated to skills-building as well as innovation. Similarly, Congress should fully fund other shortchanged features of the CHIPS and Science Act, such as ones to build the STEM workforce through scholarships, fellowships, and traineeships. Finally, as in the case of cluster development, the nation needs to better support regional efforts to train the diverse AI workforces they will need to carve out viable spots on the emerging AI map. For this, Congress should make large-scale, flexible challenge grants such as the EDA’s Good Jobs Challenge permanent.

Beyond that, there is no doubt higher education systems need more (and more flexible) resources in new formats to deliver new and relevant technology training in AI workforce development.

Accessing federal challenge grants to boost AI talent strategies: The Georgia Artificial Intelligence Manufacturing coalition

The Georgia AI Manufacturing (GA-AIM) coalition, led by the Georgia Tech Research Corporation, represents a strong example of a regional cluster development strategy in the AI sector. But it’s also a compelling intervention in statewide AI talent development. Called forth by the EDA’s BBBRC competition, the $65 million initiative will establish the AI Manufacturing Pilot Facility at Georgia Tech as a hub for research, testing, and training in AI systems across the region. Beyond that, coalition members across the state—including the Technical College System of Georgia, Spelman College, and the Georgia Minority Business Development Agency—will execute projects to expand awareness, training, and job opportunities to underserved communities and businesses. A key component of all this is preparing Georgia’s workforce for the rise of AI-enabled automation in established state industries such as semiconductors, battery manufacturing, food production, and defense. Along those lines, GA-AIM will add a new hub to the nation’s AI map, even as it advances a national model for how to accelerate the transition to automation in manufacturing while diversifying the next generation of AI leadership.

Promote the emergence of vibrant AI clusters in new places. Research investment, access to computing resources, and talent strategies won’t by themselves be sufficient to support the emergence of a more balanced AI geography across the U.S. It will also require more intentional efforts to build up vibrant AI ecosystems in more and different places. As we have seen, while a dozen or so U.S. metro areas possess the beginnings of unique AI industry clusters, too few of them appear likely to reach critical mass. Which is why the federal government should follow through on its efforts to leverage place-based industrial policy in the acceleration of emerging-sector scale-up in promising but different places.

The EDA’s fully funded and launched Build Back Better Regional Challenge (BBBRC) provides an example of how sizable place-focused challenge grants to regional stakeholder groups can accelerate the scale-up of local AI specializations. A case in point is the above-mentioned Georgia plan to channel $65 million into an ambitious push to accelerate AI-related adoption in the state’s manufacturing sectors. Such an award—dispensed through a compelling, well-run, and well-resourced funding competition—demonstrates how the federal government can effectively invest to counter AI sector geographical divergence.

In light of that, there is an urgent need for Congress to scale-up such place-based investments in emerging AI communities. One place to begin would be to fully fund two highly relevant but partially appropriated programs. Eighty-eight of the 600-plus concept outlines submitted to the NSF Regional Innovation Engines program involved AI themes, and more AI proposals will likely be submitted to the Commerce Department’s Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs program. Each of these programs was authorized at generous and appropriate funding levels, and will likely support large-scale AI development in new places depending on the award selections. However, final appropriations in the FY 2023 omnibus appropriations bill fell far short of the needed support for full build-out. Congress should rectify that shortfall, and further, build a standing capacity to make sizable place-based innovation grants into any future EDA reauthorization bill. Brookings Metro has previously provided a succinct rationale and framework for an expanded EDA.

Driving ecosystem growth in promising areas: Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs

Authorized by the CHIPS and Science Act and initially funded at the Commerce Department, the Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs program exemplifies the kind of federal strategy that could make a difference in countering the excessive concentration of early AI activity. That’s because the program (and the broader CHIPS and Science Act) explicitly prioritizes both AI and geographic areas in need of investment. The legislation designates AI as a “national-security critical technology” that should be elevated in economic development, while the program intends to catalyze growth in 20 geographically distributed areas that are not already home to leading technology clusters. As such, fully funding the program and using it to galvanize promising regional AI development through major place-based challenge grants represents a powerful model for building new AI centers.

Just as federal “top-down” approaches are critical to countering the excessive concentration of AI activity, so are state- and local-level “bottom-up” initiatives.

To be sure, the federal government is uniquely well positioned to mobilize large quantities of capital to promote AI diffusion. However, states and regions are closer to the action and often better able to plan and work in detail to advance the potential of their local industries, institutions, and workforces.

More specifically, locally executed place-based interventions can leverage the efficiencies that come from mobilizing the most immediately relevant actors, organizations, and networks to deliver programs with a heightened level of focus. This underscores that state and regional initiatives will need to play a role as the nation moves to build up more variegated AI ecosystems in more places.

Some regions are already doing this, aided by federal initiatives such as the BBBRC and Regional Innovation Engines programs. These efforts—like the federal ones—are expanding local research, democratizing computing and data access, promoting cluster development, and investing in talent through bottom-up planning, governance, and execution.

In Indianapolis, leadership groups such as the Central Indiana Corporate Partnership (CICP) are developing the ambitious AnalytiXIN initiative, which among several objectives aims to unlock the AI R&D capacities of three in-state universities through applications development at the 16 Tech innovation district. The initiative is also widening data access by building out a shared health data platform that links consented clinical and genomic patient data, as well as developing factory efficiency models and analytics using AI and machine learning (ML) tools.

For its part, a key portion of greater Pittsburgh’s winning BBBRC initiative, the Southwestern Pennsylvania (SWPA) New Economy Collaborative, will support the Expanded Pathways to New Economy Careers project, which aims to grow the region’s existing AI- and robotics-related workforce training systems to reach beyond the typical urban core and Tier 1 universities, where it is currently concentrated. As such, the effort exemplifies the kind of bottom-up initiative through which regions can advance their standing in AI by assembling the necessary skills base and ensuring its inclusivity, including in underrepresented and rural areas.

At the same time, numerous regions are engaging in smart cluster development—sometimes motivated by the new generation of federal place-based challenge grants.

For example, since 2020, the San Diego Regional Economic Development Corporation has released four detailed studies tracking the state of AI and ML within key local clusters such as life sciences, transportation, and cybersecurity. These reports are providing an invaluable baseline description of the region’s AI/ML activities and building a platform for segment-specific policy development.

Yet states and regions also need to do more to access necessary resources and build up new AI ecosystems. The challenge ahead for these non-superstar places will be considerable. The geography of research hubs, major technology companies, and talent continues to concentrate on the coasts. Likewise, R&D resources, computation resources, and data remain difficult to access at scale without government involvement.

With that said, bottom-up “self-help” by states and regions can not only target high-value uses of federal resources, but also discover new resources, develop new use cases, and unleash local talent. Along these lines, states and regions with promising starting points should pursue the following objectives:

Expand and deepen R&D. With winner-take-most dynamics ensuring Big Tech and star university dominance of U.S. AI activity, states and regions need to advance systematic and highly focused initiatives to grow differentiated local R&D concentrations at their institutions. Multiple university-based consortia are taking the lead on this, including the Alabama Artificial Intelligence Center of Excellence—a public-private partnership in Auburn, Ala. that involves eight colleges and universities, three cities, and data center AUBix.

Tuned to local tech sector specializations, such campaigns can and should target both the current federal push to democratize investment as well as national and local philanthropy. On the federal side, the new government focus on place-based and geographically inclusive innovation in AI and other areas means that programs such as the NSF’s AI Research Institutes, the NSF’s Regional Innovation Engines, and the EDA’s forthcoming Regional Technology and Innovations Hubs are all plausible sources of R&D investment for regions. Georgia Tech’s acquisition of significant R&D funding for its AI Manufacturing Pilot Facility shows how the new federal programs can be leveraged. Philanthropy can also play a critical role; in Indiana, for example, support from the Lilly Endowment has been critical in helping CICP enlist the under-commercialized AI capabilities of the state’s three major universities in an urgent research and economic development partnership.

Prioritize inclusive data and computation. States and regions also face challenges in boosting local data and computational resources. However, the challenge is not insurmountable. In addition to federal grants, industry-university partnerships can be an effective model for pulling both data and computation resources into new areas. AnalytiXIN has been developing its shared health data platform as a working collaboration between Eli Lilly, Indiana University Health, the Indiana Biobank within the Indiana University School of Medicine, the Indiana Health Information Exchange, and other partners. For its part, north-central Florida and the University of Florida (UF) have been able to establish new relevance in AI by securing powerful new computational tools through a $70 million partnership with NVIDIA and UF alumnus Chris Malachowsky, NVIDIA’s co-founder. To be sure, such enterprises depend on fortuitous relationships between particular people and firms. Even so, the Florida accomplishment is an impressive example of how states and regions can and must bootstrap gains that will bolster their AI strengths.

Bootstrapping philanthropy to secure computation access: The University of Florida’s partnership with NVIDIA

The University of Florida’s (UF) partnership with NVIDIA shows how higher-education-oriented philanthropy focused on computing resources can support the emergence of AI activity in new locations. In the case of the UF-NVIDIA partnership, the core gift from NVIDIA co-founder Chris Malachowsky involved critical computing power, and a key aspect of the project is the broad view the university is taking on how to deploy this expanded power. UF’s provost has emphasized that the university wants to integrate AI across all of its departments to create broad familiarity with machine learning technology. In addition, the university established a NVIDIA-supported Deep Learning Institute, which developed a curriculum for UF students as well as local community members looking to better understand and prepare for AI’s labor market impacts. This includes making AI available to the full economic region, including K-12 students and multiple Florida colleges and businesses. In this way, the partnership provides an interesting example of the importance of high-end computing resources and how they can be leveraged to support broader regional development.

Invest in talent. The growing recognition of workforce development as a critical enabler of technology-based economic growth creates an additional opportunity for progress on building AI workforces in new hubs. The new place-based industrial strategy programs at the federal level welcome talent strategies; in fact, both of the AI-related BBBRC winners (from Georgia and Pittsburgh) dedicated tens of millions of dollars of their funding awards to AI skills-building, including for underserved people and small and midsize enterprises. So too did finalist Louisville, Ky. in a proposal aiming to establish the region as a national hub for digital health care by broadening the region’s AI talent pipeline and supporting AI adoption in the health care sector. All of which suggests that every region serious about increasing its AI prominence needs to shape a sharp, data-informed AI talent strategy to both organize its own activities and seek federal and other funding. (States can especially lead in this.) Another example of the interplay between research, computation, and skills development is the AI TENNessee Initiative, which is making available seed funds for explorative research grants, collaboration grants, and team-building activities.

Promote the emergence of vibrant AI clusters. Finally, excitement about AI has for several years been prompting prominent state and local economic development organizations to support AI ecosystem-building by investing directly in AI startups and clusters. For example, Ohio Third Frontier, the Maryland Technology Development Corporation, the Michigan Economic Development Corporation, New York Ventures, and other actors have all in recent years provided funds to commercially promising new firms. Such direct investments are one way to strengthen local commercial activity, but another strategy—reflected in the federal government’s place-based development challenges—looks beyond individual firm development and toward nurturing interactions across whole ecosystems. Here is where states and regions can and should look to the new federal grants as sources of support to help them design and implement AI cluster strategies.

For example, the NSF’s Regional Innovation Engines and the EDA’s Regional Tech Hubs (as well as other new programs) are not just sources of R&D funding—they are designed to accelerate ecosystem-based tech development. Both programs provide planning grants for the design of in-depth industry strategies to promote advanced-sector growth. Both also hold out competitive opportunities to win large-dollar implementation grants. What’s more, AI sits squarely among the technologies prioritized for investment through the new programs. Given that, states and regions should consider organizing consortia to craft compelling AI regional strategies, use them to mobilize investment, and then execute them. The $65 million Georgia AI Manufacturing initiative shows what it looks like when a region is ready to shape a strategy, seek federal funding, and deliver on it.

Winning a funding award is not the only form of success. Even a strong but unsuccessful proposal for federal funding can be tremendously valuable if it mobilizes state and regional support for a compelling AI growth strategy.

The Biden administration appears increasingly aware of the need to promote geographic inclusion and dynamism across the whole of the United States. At the same time, the administration is alert to the opportunities and challenges AI poses, including in its compelling new generative form. States and cities, for their part, have tended to lag behind the federal government in developing specific responses to AI development; however, this too is changing.

Yet more needs to be done. The pace of the AI policy response remains too slow given the speed at which the technology is developing. What’s more, the stakes of promoting better distributed AI innovation and growth are also very high. Much has been written about the tendency for technological change to catalyze stubborn “winner-take-most” dynamics and erode middle-income jobs. AI appears likely to follow to these trends, yet it also appears to be able to encourage productivity growth after decades of stagnation. Such a contribution would be welcome for the economy at large, especially if it preserved quality employment. So it is crucial that policymakers work to promote the geographic diffusion of AI activity along with inclusive ways to access it.

This report therefore makes the case that a combination of local, state, and federal initiatives will be necessary to spread AI innovation and productivity gains more broadly across the U.S. To achieve these goals, the federal government is likely to be the best-placed actor for mobilizing the resources necessary to promote widespread AI growth, but states and cities have a key role to play too. Such initiatives should focus on improving the distribution of AI-related R&D, widening access to computing power and data, supporting the emergence of an AI workforce, and promoting the emergence of AI clusters in new places. Through intentional engagements along these lines, the U.S. may well be able to align an AI revolution with benefits that are socially and geographically distributed across the nation.

Berube, Alan, and Max Berube. 2021. “How Louisville can become a stronger and more equitable hub for AI and data economy jobs.” Washington. Brookings Institution.

Bipartisan Policy Center. 2020. “Cementing American artificial intelligence leadership: AI research and development.”

Bloom, Nicholas; Tarek Alexander Hassan, Aakash Kalyani, Josh Lerner, Ahmed Tahoun. 2021. “The diffusion of disruptive technologies.” Working Paper 28999. National Bureau of Economic Research

Eloundou, Tyna, and others. 2023. “GPTs are GPTs:” An early look at the labor market impact potential of large language models.” San Francisco. OpenAI.

Meserole, Chris. 2018. “What is machine learning?” Washington. Brookings Institution

Muro, Mark, and Sifan Liu. 2021. “The geography of AI: What cities will drive the AI revolution?” Washington: Brookings Institution.

Muro, Mark, Jacob Whiton, and Robert Maxim. 2019. “What jobs are affected by AI?” Washington. Brookings Institution.

National Artificial Intelligence Research Resource Task Force. 2023. “Strengthening and democratizing the U.S. artificial intelligence ecosystem: An implementation plan for a national artificial intelligence research resource.” Washington.

National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence. 2021. “Final report: National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence.” Washington.

Omaar, Hodan. 2021. “RFI Response National AI Research Resource.” Washington. Center for Data Innovation.

—-. 2020. “How the United States can increase access to supercomputing.” Washington. Center or Data Innovation.

Nestor Maslej and others. 2023. “The AI Index 2023 Annual Report.” Palo Alto. Institute for Human-Centered AI. Stanford University.

Bipartisan Policy Center. 2020. “Cementing American artificial intelligence leadership: AI research and development.”

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Brookings Metro would like to thank the following for their generous support of this analysis and our metropolitan advanced economy work more broadly: Central Indiana Corporate Partnership, the Columbus Foundation, the Columbus Partnership, the George Kaiser Family Foundation, the Henry Hillman Family Foundation, and Microsoft. The program is also grateful to the Metropolitan Council, a network of business, civic, and philanthropic leaders that provides both financial and intellectual support to the program.

In addition, the authors are grateful for generous support for the Brookings Institution’s Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technology (AIET) Initiative.

The authors also appreciate the input of colleagues but outside and inside Brookings.

Special thanks go to the following external colleagues: David Johnson, Sifan Liu, Pamela Mishkin, and Nathan Ringham. Within Brookings, the following staff offered input and counsel: Alan Berube, Chris Meserole, Joseph Parilla, and Yang You. In addition, the authors wish to thank Leigh Balon, Michael Gaynor, David Lanham, and Erin Raftery for editorial and communications expertise. Thanks to Carie Muscatello and Alec Friedhoff for layout and graphic design.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).