Editor’s Note: This is the full text of Robert Puentes written remarks prepared for the Fifth U.S./China Investment Forum held April 11, 2012 at the U.S. Department of Treasury.

Undersecretary Brainard, Vice Chairman Xiaoqiang, thank you for the opportunity to be here today. This discussion about new ways to finance investments in U.S. infrastructure is very relevant and timely. Throughout the U.S., there is real interest in a new infrastructure vision to support a more productive and sustainable economy.[1]

This vision is made up of transformative investments that have to the power to change our economic trajectory through modern ports and gateways, intelligent transportation, renewable energy and cleantech installations, advanced telecommunications systems, and new, technologically-driven forms of economic development. Investing in infrastructure has the added benefit of providing much-needed jobs, especially in the construction industry where unemployment rates stubbornly remain twice the national average.[2]

The challenge is that the nation’s economic recession and tense new focus on austerity means public resources for infrastructure are strained. As financial markets have contracted all actors are suffering under tightened credit supplies. Stretched budgets at all levels of government have led to a larger gap between infrastructure costs and revenues. As a result, meeting the nation’s great needs for funding and financing infrastructure requires an “all of the above” strategy. This is especially true for state and local governments and elected officials, as I will explain. I firmly believe there is a clear need for a national infrastructure bank to finance multi-jurisdictional projects of national significance.[3]

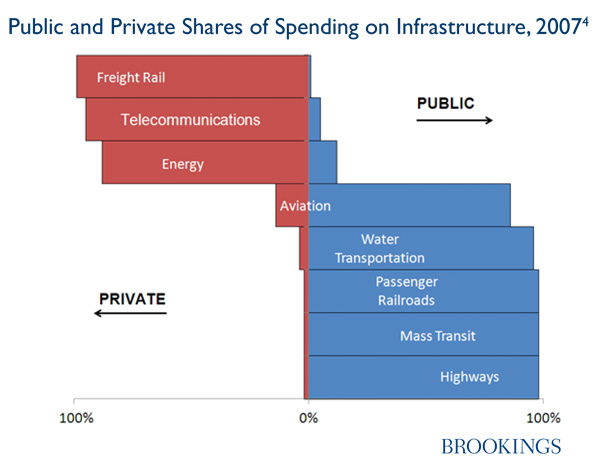

However, in the absence of congressional action, states and localities are stepping in to finance the kind of major investments necessary to support the next economy. States and municipalities retain primary authority over selection, design, and control of the vast majority of infrastructure projects. How choices are made about which to fund is exceedingly complex and depends on funding sources, jurisdictional concerns, and political negotiations. Federal dollars for transportation and water mostly flow to the states who then work with their municipal counterparts to decide on specific investments. For transportation, this is also done in partnership with other entities on the metropolitan level such as the 400 metropolitan planning organizations and the multitude of special purpose bodies such as sea, airport, and toll road authorities and public transit agencies. Other areas of infrastructure, such as energy, telecommunications, and freight rail investments, are dominated by the private sector typically with federal and state regulatory oversight (see figure.) Public and Private Shares of Spending on Infrastructure, 2007[4]

Increasingly, public infrastructure investment is taking place through innovative finance tools, revolving loan funds, trusts, and so-called “banks.” Most of these offer direct loans at low interest rates to public and private entities, while some also offer grants, loan guarantees, bonds, and other financial instruments. According to forthcoming Brookings research, since 1995 thirty-three states have used infrastructure banks and funds to invest nearly $7 billion in over 900 different projects. These projects range from local road maintenance and highway construction to emergency relief for damaged infrastructure. The structure of the banks and projects in which they invest reflect the diversity of needs and resources across the U.S.[5]

On the local level, Mayor Rahm Emanuel recently announced the creation of the Chicago Infrastructure Trust (CIT) as a market-oriented institution that attracts private capital interested in steady returns and makes investment decisions based on merit and evidence rather than politics. Like California’s I-Bank it cuts across different types of infrastructure such as transportation and telecommunications, and like Connecticut’s Green Bank it emphasizes the generation, transmission, and adoption of alternative energy. The CIT will be capitalized through direct investments from private financing organizations some of which have already expressed interest that could reach $1 billion or more in total investment capacity. The Chicago plan highlights an important point with respect to differences among states and municipalities in the U.S. today. While some states and cities are ambitiously pursuing innovative sources of infrastructure finance-such as partnerships with private and foreign investors-many others are not. For example, only 24 states undertook at least one public/private partnership (PPP) transportation project since 1989. Florida, California, Texas, Colorado, and Virginia alone were responsible for 56 percent of the total amount of all U.S. transportation PPP projects during this time.[6]

So why are some states more active in attracting private infrastructure financing? No doubt this is partly based on the unique conditions, traditions and cultures in certain places. But there are also a number of other, more practical, reasons. For one, it is difficult to attract private interest in public projects if investors do not know what kinds of projects are available. Latin American countries regularly pull together trade shows to showcase opportunities for Bus Rapid Transit projects, for example. Partly to address this problem in the U.S., California, Oregon, and Washington are partnering on something called a West Coast Infrastructure Exchange as a platform to spotlight and catalog specific projects, opportunities, and grow the market for private infrastructure firms to invest in domestic infrastructure. Next, other than the obvious legal authority that provides the necessary statutory allowance to get into contracts with a range of partners, state legislation is also essential to send a strong signal that a state is open to private and foreign involvement in infrastructure financing and delivery. It provides predictability for the private sector engaging in a partnership with the public sponsor. On the other hand, the lack of state PPP legislation can prove a real hindrance to the development of the PPP market. The 2007 failed $12.8 billion bid for the lease of Pennsylvania Turnpike would have benefited from having state PPP legislation in place before the negotiation began. Thirty-one states have PPP enabling legislation for highways, roads, and bridges, and 21 have PPP legislation for transit projects. Finally, many states simply lack the technical capacity and expertise to consider such deals and fully protect the public interest. To address this problem, countries, states, and provinces around the world have created specialized institutional entities-called PPP units-to fulfill different functions such as quality control, policy formulation, and technical advice. Today no less than 31 countries have a PPP unit at the national or subnational level. In the U.S., three states (Virginia, California, and Michigan) have established dedicated PPP units. Lastly, I want to briefly describe how metropolitan areas around the country are increasingly acting on their own to envision, design, and finance the next generation transportation system in America. Those places-especially in the West-are taxing themselves, dedicating substantial local money, and effectively contributing to the construction of the nation’s critical infrastructure system.[7]

Transit projects in Denver, New Mexico, and the Salt Lake City area are all substantially financed by voter-authorized payroll or sales tax increases and epitomize the new spirit of bottom-up initiative. In metropolitan Phoenix, voters approved a proposition in 2004 that extended a half-cent sales tax for regional transportation for another 20 years. That bit of local effort will generate over $11 billion over time to expand regional transit service but, like Los Angeles’ Measure R, it will also dedicate billions for freeway upgrades, additional lanes, and improved interchanges, including substantial improvements to the national interstate system. Other major metro areas like Las Vegas, Charlotte, St. Louis, Oklahoma City, Seattle, and Milwaukee have also gone to their voters for approval of ballot initiatives to fund a mix of light rail and bus lines, highway projects, commuter rail, and corridor preservation. A coalition of business and civic leaders in the Dallas Metroplex is pushing the state legislature to give metros in Texas the authority to do the same. In short, metropolitan areas across the country are laboring hard to keep up with system maintenance, enhancement, and expansion needs-even along national corridors-on which they are investing substantial local resources. At the Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program we are working with a set of high level civic, corporate, political, and philanthropic leaders across the U.S. on dedicated policy and research agenda that describes both the opportunities and challenges in financing the next generation of U.S. infrastructure investments. By doing so we hope to “crack the code” and lay out a federalist policy and practice agenda to expedite implementation, unlock the capital, and create jobs and economic value in the U.S.

[1] U.S. Department of Treasury and Council on Economic Advisers, “ A New Economic Analysis of Infrastructure Investment,” Washington: U.S. Department of Treasury, 2012.

[2] Bureau of Labor Statistics, CES Current Employment Statistics, Table A-14. “ Unemployed persons by industry and class of worker, not seasonally adjusted.” Washington: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

[3] Robert Puentes,“ Testimony on the Proposal for a National Infrastructure Bank, Committee on Ways and Means Subcommittee on Select Revenue Measures,” Washington: U.S. House of Representatives, May 13, 2010.

[4] Sources: Congressional Budget Office, “Public Spending on Transportation and Water Infrastructure”, “ “Relation of Fixed Investment in Structures (by type) in the Fixed Assets Accounts to the Corresponding Items in the National Income and Product Accounts.” Does not include private spending on vehicles.,” Washington: Bureau of Economic Analysis, November 2010.

[5] It is important to note that rather than bringing a tough, merit-based approach to funding, many state infrastructure banks are simply used to pay for the projects selected from the state’s wish list of transportation improvements, without filtering projects through a competitive application process. A better approach would be for states to evaluate projects according to strict return on investment criteria. Such an approach is analogous for how the federal government should establish a national infrastructure bank. See: Robert Puentes, “ “State Transportation Reform: Cut to Invest in Transportation to Deliver the Next Economy”,” Washington: Brookings, 2011.

[6] Emilia Istrate and Robert Puentes,“ “Moving Forward on Public Private Partnerships: U.S. and International Experience with PPP Units”,” Washington: Brookings, 2011.

[7] Mark Muro and Robert Puentes,“ “Helping Those Who Help Themselves”,” Washington: The New Republic, The Avenue, May 27, 2010.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

TestimonyNew Approaches for Infrastructure Finance: State and Local Perspective

April 11, 2012