Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Hong Kong at the beginning of July to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover to China and swear in Carrie Lam as the new chief executive. For Xi’s first visit as president of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Beijing’s propaganda apparatus—including its outlets in Hong Kong—mounted an over-the-top campaign to convince the Hong Kong public and the world that the territory had thrived under the “one country, two systems” framework and would continue to.

Whether the propaganda barrage convinced the Hong Kong people remains an open question. But it did seem to disguise recent efforts by Beijing to blur the lines between the two systems, which many in Hong Kong view as the backbone of the post-1997 arrangement. And, only weeks following Xi’s trip, other political developments have raised concerns that key features of Hong Kong’s special governance framework are under threat.

New constraints?

The “two systems” in the “one country, two systems” governing model guarantees the continuation of Hong Kong’s market economy as well as the rule of law and political and civil rights for all Hong Kong’s residents. Since the Umbrella Movement in 2014, however, Beijing has been increasing its influence in and control over Hong Kong. The disappearance of several booksellers in 2015 and the kidnapping of Hong Kong-based billionaire Xiao Jianhua last December indicate that someone in the PRC system is trying to enforce Chinese law in Hong Kong, a violation of the Basic Law that serves as the territory’s constitution.

Moreover, a renewed push to enact a national security law fosters fear that such a law could abridge civil and political rights. And, worries continue that takeovers of Hong Kong newspapers by pro-Beijing businessmen is shifting their stance in a direction that is less critical of mainland policies.

This liberal foundation of the “second system” is as important today as it was 20 years ago—for operating Hong Kong’s capitalist economy; for providing its government with useful feedback about its performance; and for bolstering the reputation of China’s government that it will sustain its legal commitments over time. True, freedoms can be abused. But the long-term costs to Beijing of restricting freedoms and constraining the rule of law will be higher than the benefits that might accrue from a more democratic—but docile—political system.

“Do You Solemnly Swear?”

Also raising concern are the disturbing judicial cases to expel anti-establishment (pro-democracy or “localist”) legislators from the Legislative Council (LegCo) because they allegedly did not say their oath properly. In effect, the Hong Kong government and Beijing are using Hong Kong courts to root out anti-establishment politicians to change the balance of power in LegCo in their favor.

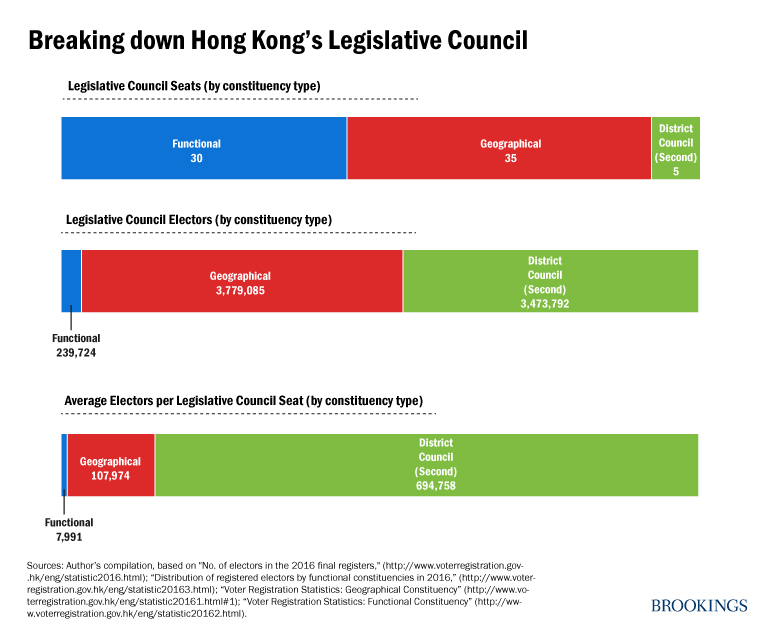

By way of background, just over half of LegCo members are selected through popular elections in geographical constituencies. Repeatedly, over half of those seats have gone to candidates who are anti-establishment. The other half of LegCo members are elected in “functional constituencies” that are made up of people or entities from specific economic and social sectors. The number of people voting in these constituencies is usually fairly small, and most tend to favor the establishment, or pro-Beijing policies, and the political status quo. This same type of imbalanced representative system is used for selecting the chief executive. A stable majority of Hong Kong people dislike these arrangements and favor the popular election of the chief executive and the end of functional constituencies.

For the geographical constituencies in the 2016 LegCo elections, Beijing probably hoped that voters would be unhappy with the political instability of the previous three years—which stemmed from electoral reform efforts—and thus, elect more establishment candidates. But voters surprised Chinese leaders by electing more anti-establishment candidates than they had four years earlier, so that these members controlled a majority of the geographical constituency seats. (The establishment was able to use its dominance in the functional constituency seats to retain an overall majority.)

As we explained last fall, some of the more radical anti-establishment victors chose, perhaps unwisely, to make a symbolic protest by altering the LegCo oath. Beijing seized on this as an opportunity to try to position itself on the side of the rule of law. After two rounds of oath ceremonies, the Hong Kong government (then led by Chief Executive C. Y. Leung), sued in local courts to expel two anti-establishment members on the grounds that they did not properly take the oath. The court ultimately ruled in favor of the government, but not before Beijing took action that raised questions about its commitment to the rule of law in Hong Kong. The Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC-SC) issued an interpretation of the Basic Law, even before the Hong Kong court even heard the case. Therefore, many viewed the interpretation as Beijing effectively telling the local court how to rule. The drama, however, did not end there as the C. Y. Leung government proceeded to file suit against four additional anti-establishment LegCo members, again for their improper oaths. On July 14, the Hong Kong High Court ruled to ban the four lawmakers. In this ruling, Judge Thomas Au Hing-cheung weighed heavily on the NPC-SC interpretation to justify his decision on what he deemed sincere or not.

What Happens Next?

China may have won this battle over who sits in LegCo, but it has not won its Hong Kong “war.” The court rulings will not only shape near-term political machinations but also could affect the quality of governance in the territory and prospects for renewed electoral reform.

How the anti-establishment camp should proceed

In the short term, the pro-Beijing leadership of LegCo can now change the rules governing the legislative process because the anti-establishment no longer has a majority of the geographical constituency members, which provided a veto for such changes. The establishment legislators are most likely to target the rules concerning filibustering, which anti-establishment members have used to delay and obstruct consideration of bills.

But this advantage will probably not last forever. After all legal proceedings conclude, there will likely be by-elections to replace the six members that the courts expelled, and there is no sign that voters in the affected districts believe that the expulsions were justified. If anything, the court decisions may intensify their anti-government sentiment and voters may well restore the anti-establishment’s strength in LegCo.

[V]oters may well restore the anti-establishment’s strength in [the Legislative Council].

To ensure this outcome, the many anti-establishment parties will have to avoid internal competition. In each of the districts that the disqualified legislators represent, anti-establishment candidates got more total votes than pro-Beijing candidates. However, the pro-Beijing camp only fielded three to four candidates, while the pan-democrats had anywhere from seven to 10 different parties running in each district. Reclaiming the lost seats is the best opportunity the anti-establishment camp has to prove to the new Hong Kong government, as well as the central government in Beijing, that it has wide support from the public. And, the anti-establishment has other tools at its disposal, including mass protest (in 2003, for example, public demonstrations against a national security law forced the government to back down).

Carrie Lam’s conundrum

Let us assume that Carrie Lam—who took office as chief executive on July 1—is committed to addressing the policy challenges that Hong Kong faces: chronic housing shortages, growing income inequality, resistance to major infrastructure projects, and increased economic competition from mainland cities, to name a few. Let us also assume she understands that in order to address these issues, she must foster a working political environment, and that means bridging the polarization by empowering moderate legislators of the pan-democratic camp.

It was perhaps no coincidence that on the day after the most recent LegCo expulsion order, she stated that she does not intend to target additional pro-democracy lawmakers. This was a signal to the anti-establishment camp, the Hong Kong public at large, and Beijing, which earlier threatened to go after a total of 15 legislators for altering their oaths. But, Mrs. Lam doesn’t have complete control over the situation as non-government establishment actors have sought their own judicial reviews concerning the oaths of several additional legislators. If those proceed, it will undermine her strategic interest of ending this issue in order to conciliate the anti-establishment and govern well.

The chances for electoral reform

Although anti-establishment parties disagree on goals, strategy, and tactics, they probably do agree in principle on the need to transition Hong Kong to a fully democratic system, in which the chief executive and all members of LegCo are picked through popular elections. Indeed, the government will likely need to keep the door open to electoral reform if it is to secure the support of moderate elements of the anti-establishment for its other policy goals. Carrie Lam has suggested that the political climate for resuming electoral reform in the short term is unfavorable, but she did leave the door open for reform at a later date by saying that allowing “voters to elect their own chief executive by one man, one vote is going to be conducive to governance.”

One of the necessary conditions to get a more favorable climate will be an anti-establishment camp that is sufficiently unified and constructive in its approach to electoral reform, and therefore does not outright reject whatever approach the government offers. At the end of the day, a politically viable proposal must ensure a genuinely competitive contest in which the candidates reflect the spectrum of views held by Hong Kong voters. It would then be up to the anti-establishment to be able to take “yes” for an answer. Perhaps the lessons learned from the failed 2014-2015 reform proposal, plus the more recent court decisions, will induce moderates and activists to work together and forge compromises.

Additionally, in its effort to reduce the number of LegCo’s anti-establishment members, Beijing appears to have ignored why over 55 percent of voters elected these legislators in the first place: to govern in coordination with the executive branch and address society’s problems. Because political sentiment in Hong Kong will likely continue to favor the anti-establishment camp (in spite of its tactical mistakes over recent years), governing ultimately will require some degree of cooperation and compromise. That in turn requires some degree of mutual trust, which has been the most serious casualty of the political conflicts in the last four years.

While many of these issues must be solved within Hong Kong, they also have implications for regional countries and the United States. First, the city is still an important economic hub, and global businesses need stability in Hong Kong’s second system to maintain confidence for investments. Hong Kong provides a powerful demonstration of how open markets, transparent regulation, and political and civil rights support growth and prosperity. Additionally, how China respects Hong Kong’s rule of law could be an indicator on how it will treat other international agreements. In a press conference over the anniversary weekend, a Chinese official asserted that arrangements laid out in the Sino-British Joint Declaration “are now history and of no practical significance.” (Beijing did walk back the statement a bit by clarifying that it still planned to uphold one country, two systems under the Basic Law.) All the same, it is important that the international community and the United States continue to shine a spotlight on efforts to restrain civil and political rights or the rule of law, as Hong Kong could be a testbed for strategies or doctrines pushed by China in other arenas.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Inside the struggle for China’s “two systems” in Hong Kong

July 27, 2017