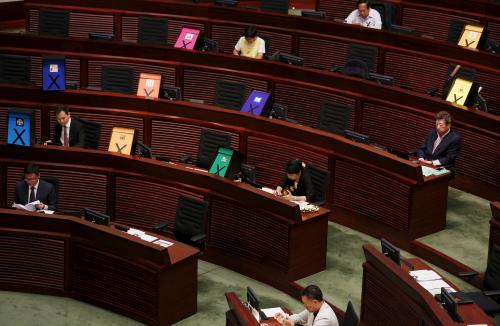

Voters in Hong Kong want political change and oppose Beijing’s recent policies in its special administrative region. They made this clear once again in the September 4 Legislative Council (LegCo) elections. In a vote with record turnout, moderate and radical members of the existing pro-democracy camp captured 22 seats of the 70-seat legislature. But they were joined by pro-independence Localist candidates, who emerged from the 2014 Umbrella Movement and won eight seats, with 19 percent of the total vote share. Overall, anti-establishment candidates received almost 60 percent (the reason they won’t have a majority of seats in LegCo, though, is because Beijing designed the institution to ensure that wouldn’t happen). These results revealed that politics in Hong Kong remained divided.

But, the chaotic start of the new LegCo term on October 12 has shown that deep-rooted mistrust in Hong Kong politics, as well as the preference for symbolic politics, does not bode well for future policymaking and could impact the foundation of Hong Kong’s governance.

So wait, what happened?

Let’s do a quick recap of the events that have upended Hong Kong in the past two weeks. At the start of the new LegCo term, each member was required to take an oath, pledging allegiance to Hong Kong as the special administrative region of the People’s Republic of China. Seems simple enough. But, the oaths of five candidates—four Localist and one pro-Beijing—were later deemed invalid, because they either added unacceptable commentary or omitted key phrases. For instance, and not surprisingly, the Localist members’ failed oath-taking included some incendiary language and pro-independence protests. On October 19, the five members were scheduled to retake their oaths, as allowed by the recently elected LegCo president, Andrew Leung Kwan-yuen. The pro-Beijing members, however, walked out of the LegCo chamber, thus taking away quorum and delaying the oath ceremony.

Just to add one more layer of complexity, but an important one: Late on October 18, the Hong Kong government filed a legal challenge to prevent two of the outspoken Youngspiration party lawmakers, Sixtus Baggio Leung Chung-hang and Yau Wai-ching, from being sworn in again because they violated the Basic Law, or Hong Kong’s mini-constitution. While the High Court of Hong Kong struck down that injunction, it did grant a judicial review on Andrew Leung’s decision to allow the contested lawmakers to re-take their oaths. That hearing is scheduled for November 3, and Andrew Leung has confirmed that he will not allow another oath ceremony until the judicial review decision is made. If the court sides with the government, then the two Youngspiration lawmakers will lose their seats.

Name of the game: Divisive and symbolic politics

Since the 2000s, Hong Kong’s political system has become increasingly divided, with mistrust driving wedges between the pro-Beijing, or “establishment” camp, and the pan-democratic camp, and even dissolving unity among pan-democrats as radical forces gain popularity.

The election of Localist candidates on September 4 created yet another group in the anti-establishment camp. They share the tactical approach of radical politicians but are a generation younger. It was students who took the lead in the Umbrella Movement in the fall of 2014, when people protesting Beijing’s approach to political reform took over three major Hong Kong thoroughfares for two months. The students gained great notoriety during the occupation, and eight of their number rode that popularity to electoral victory.

But it wasn’t just their youth that distinguished the new activists (and now elected officials). They focused solely on Hong Kong as a unique society; hence the name “Localists.” Unlike their elders, they cared nothing for changing the authoritarian system in the rest of China, and some Localists advocate political independence from China at some time in the future. Consequently, the new Localist members of LegCo brought a distinct mentality to LegCo’s operation and procedures.

The pro-Beijing members certainly played their part in stoking the partisan divide as well. While some members were apprehensive about a walkout after their failed attempt during the political reform proposal vote in June 2015, the act ultimately exhibits a shift in Hong Kong political theater. Indeed, there was public outcry against the Localist’s oath tactics, which likely spurned establishment lawmakers to proceed with the demonstration. But an establishment camp staging a walkout—once a stalwart tactic for pan-democratic forces—creates legislative instability and could impede policymaking for the next four years. This is especially bad news for the people of Hong Kong, who not only crave a more democratic system, but also feel more and more marginalized by economic inequality. Without needed legislation, Hong Kong residents are likely to turn to the strategy they know well: mass demonstrations. As the Umbrella Movement showed in 2014, grandstanding tactics might garner global attention but they do not always achieve the intended objective, and further complicate relations with Beijing.

Why did the Localist LegCo members bother to make an issue over the oath? The prospect of Hong Kong independence is zero, after all. On the one hand, young politicians in many places often engage in symbolic acts, claiming that they have purer motives than their elders. On the other hand, in Chinese culture the dichotomy between symbols and substance is not clear-cut. In a profound way, symbols and ritual are substance. In contesting the authorities’ right to dictate the oath for new members, the Localists are challenging the very legitimacy of the LegCo institution itself, which Beijing designed to protect the interests of some groups and block the agendas of others.

In contesting the authorities’ right to dictate the oath for new members, the Localists are challenging the very legitimacy of the LegCo institution itself, which Beijing designed to protect the interests of some groups and block the agendas of others.

It was the authorities who started this round of symbolic politics by demanding, on short notice before the election, that LegCo candidates pledge in writing that they agree that Hong Kong is an inalienable part of China. Just last week, Beijing made a similar requirement for any candidate for chief executive. Further, the young Localist members likely feel that their radical actions during the Umbrella Movement were an important factor in their election—with this mandate in mind, they did what they know. To them, it’s less about the immediate end, and more about the means.

Okay, now what’s next?

The Hong Kong government charges that by refusing to “swear allegiance to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China,” the Localist members violated the Basic Law, thereby disqualifying them from entering office. Pan-democrats say this is a violation of separation of powers (but, as the pro-Beijing camp likes to clarify, separation of powers is not in the Basic Law). The Basic Law ensures that the judiciary has final adjudication hence the importance of the judicial review process now. The wrinkle, however, is that the National People’s Congress Standing Committee in Beijing could provide an interpretation that would supersede the Hong Kong judiciary (since it would concern “affairs which are the responsibility of the Central People’s Government, or the relationship between the Central Authorities and the Region”). While Beijing has signaled that it will stay out, some in Hong Kong are still worried that such a step would provide another story in a continuing saga of Beijing encroachment in Hong Kong affairs and erosion of the “one country, two systems” governing model.

No matter what, if the Localist lawmakers are prevented from taking office, pro-democratic supporters could blame a biased Hong Kong executive, creating a toxic political environment for the upcoming 2017 selection of the next chief executive.

Commentary

Hong Kong politics are getting even more dramatic—here’s what it means

October 25, 2016