This policy brief is an adapted chapter from Richard C. Bush’s upcoming book, “Hong Kong in the Shadow of China: Living with the Leviathan” (Brookings Institution Press, 2016).

Executive Summary

Hong Kong is a special administrative region of the People’s Republic of China. Between 2013 and 2015, opinion there was deeply divided over how to reform the system for selection of the chief executive. China was prepared to allow election by all registered voters but it insisted on a nomination mechanism that would allow it to retain control over who actually ran. The democratic camp sought a system that denied Beijing such control. A compromise that probably would have allowed a genuinely competitive election was possible, but reform failed in the end because of mistrust between the pro-democracy and pro-Beijing, or establishment, camps. Rhetorically, the United States was clearly in favor of a democratic outcome, but for good reasons it remained reserved when it came to actions. Hong Kong provides a good case of the difficulties that the United States faces in promoting democracy in complex political circumstances.

Introduction

Two years ago in September, Hong Kong erupted in a mass protest. Led by student activists, the “Umbrella Movement” challenged China’s plans for reforming how the city picks its chief executive. This was the most significant pro-democracy movement since the Arab Spring. But the demonstrations fizzled out after a couple of months, and six months later the Hong Kong government’s proposal to elect the chief executive on a one-person-one-vote basis failed to secure the legislative super-majority needed to pass.

Arguably, Hong Kong is ready for full democracy. It is a modern society where democracy proponents have been active for decades and the population is essentially pragmatic. China had said it was willing to allow elections by universal suffrage in the city, something that is unthinkable in the rest of China. But when the next chief executive is selected in March 2017, it will again be by an election committee composed mainly of local people who generally support Beijing. Why, then, did the movement fail? What was the role of the United States during the long process of debate and decision? And, what does the Hong Kong experience tell us about promoting democracy elsewhere?

Hong Kong provides a good case of the difficulties that the United States faces in promoting democracy in complex political circumstances.

Background

At the outset, it is important to understand the facts of Hong Kong’s situation and how the 2014 protest movement emerged.

First, Hong Kong is a part of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as a “Special Administrative Region,” the HKSAR. Formerly a British colony, sovereignty was returned to China in 1997. Although the PRC promised a “high degree of autonomy” and has let the HKSAR government manage most policy issues, the government in Beijing remains the ultimate sovereign authority and constitutionally retains control over defense and foreign affairs issues.

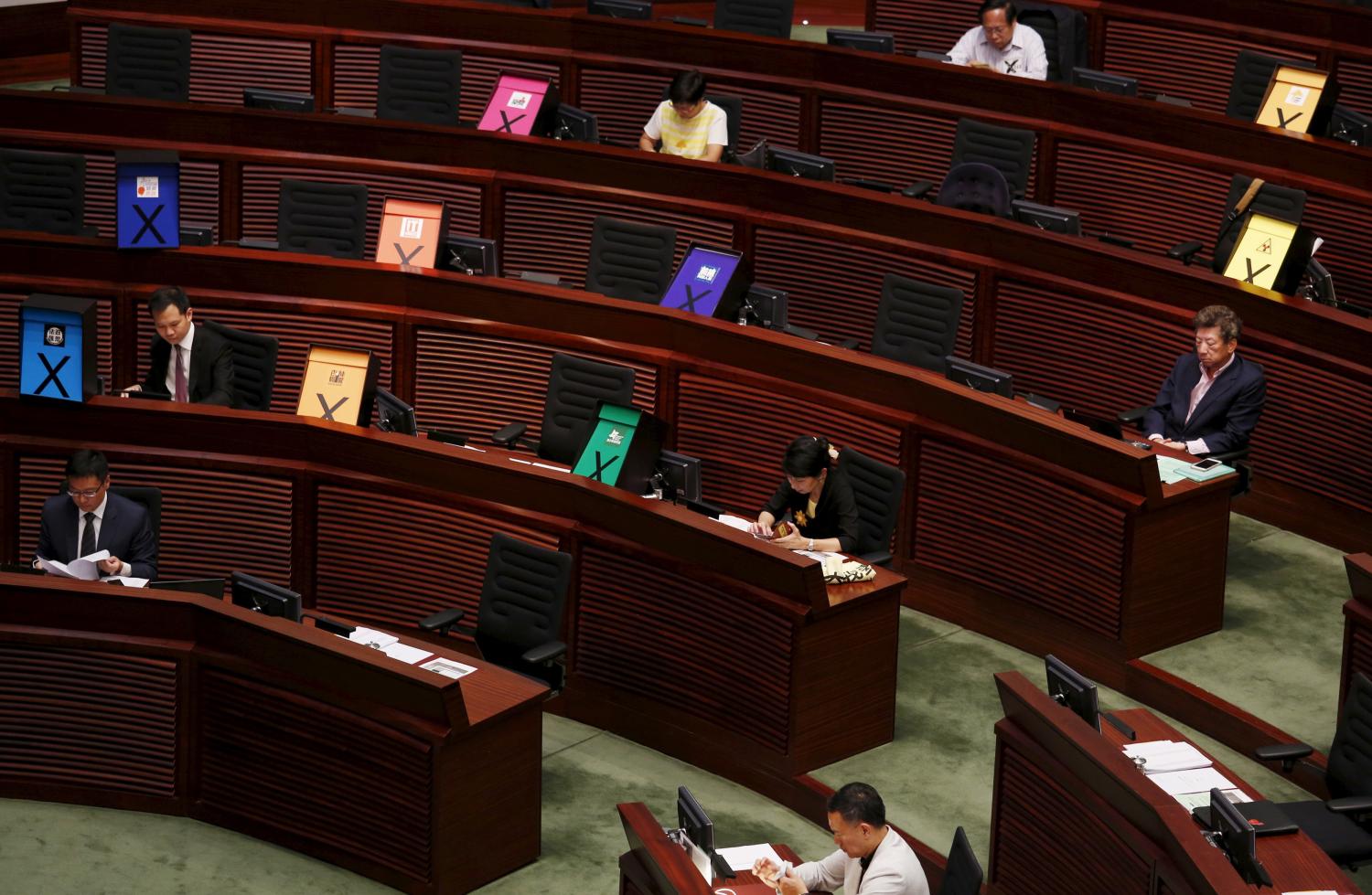

Second, Hong Kong has some of the elements of a democratic system, even under PRC sovereignty. It has a resilient rule of law. Civil and political rights are guaranteed in the Hong Kong Basic Law, the HKSAR’s mini-constitution that the National People’s Congress enacted in 1990. Although there are efforts to nibble away at those rights, the exercise of all freedoms remained strong and protected by the courts after 1997. Further, slightly over half of the members of the Legislative Council (LegCo) are chosen in free and fair elections where the results reflect the popular will.

Third, it was clear in the Basic Law that the government in Beijing wished to prevent Hong Kong politicians and parties that it mistrusted from coming to power. From 1997 to 2012, the chief executive was selected by an election committee of no more than 1,200 members, many of whom belonged to the economic elite and most of whom were pro-Beijing. Additionally, 30 out of 70 members of LegCo are selected from “functional constituencies” that for the most part have small electorates and represent business interests.

Fourth, the Basic Law stated that the ultimate aim was election of the chief executive by universal suffrage and popular election of all LegCo members. The focus of the political debates from 2013 to 2015 was changing the method for picking the chief executive (legislative reform was deferred until later).

Fifth, from the beginning, China set parameters on the scope of reform. It defined the term “universal suffrage” narrowly, in the sense of one person, one vote, and it specified in the Basic Law that “a broadly representative nominating committee in accordance with democratic procedures” would pick the candidates from whom voters would choose. The Basic Law used similar phrases when discussing the existing election committee. The implication was that China planned to control future electoral outcomes by limiting who could become a candidate.

Sixth, the divided pro-democratic forces in Hong Kong responded with a variety of tactics to oppose this “screening”: questioning Chinese sincerity; appealing to democratic principles; formulating compromise formulas; proposing radical alternative approaches; and threatening to engage in protest and civil disobedience. The democrats’ greatest leverage was China’s own requirement that any reform proposal had to pass LegCo by a two-thirds vote. Although the pro-Beijing forces had a majority in LegCo, they lacked the necessary two-thirds super-majority. The HKSAR government, which would formulate the reform bill, needed to secure the defection of at least four democratic members.

Why Did the Reform Proposal Fail to Pass?

Beijing and its Hong Kong allies clearly take some of the blame. But the democratic camp is not without fault.

Beijing’s actions

Although it decreed in 1990 that universal suffrage for electing the chief executive would come with a nominating committee, it didn’t have to stick with that position. Based on “the actual situation in Hong Kong” (a key phrase used in the Basic Law in regards to political reform), it could have shifted to allowing major political parties to nominate candidates, which would have created a competition among a few centrist candidates.

Instead, China ignored the profound changes that had occurred in Hong Kong since it first engaged Britain on a reversion agreement. The HKSAR had gone from being a purely economic city to a very lively political place, where citizens took advantage of their political freedoms to voice criticisms of the status quo. But Beijing chose its strategy of co-opting Hong Kong’s economic elite and ruling indirectly through them with mechanisms like LegCo’s functional constituencies.

The very strategy Beijing had adopted to ensure stability and control was producing the opposite.

In the process, Chinese leaders ignored a critical reality: Although Hong Kong remains prosperous, it is increasingly unequal—in income, wealth, and access to education and employment. The middle class that built Hong Kong share less and less of the benefits of growth. Moreover, they have watched an economic elite use its preferential access to political power to exacerbate social and economic inequality. So democratization became important not just for its own sake, but because it would help reduce both political and economic inequity. To promote greater democracy, Hong Kong citizens have used the very freedoms that China had granted in the Basic Law, but political protests became less orderly than they had been in the HKSAR’s early years. The very strategy Beijing had adopted to ensure stability and control was producing the opposite.

China made another misstep. Beijing policymakers apparently believed that the United States was promoting unrest in order to bring about a “color revolution” in Hong Kong, which it would then use as a platform to destabilize China itself, a charge repeated daily in the communist media. There was absolutely no basis for the belief but it gave Beijing a pretext for ignoring the local sources of unrest and the way its own policies had fed them.

Finally, China did an awful job at public relations. It took a hard line on what Hong Kong had to accept in order to get universal suffrage (a stacked nominating committee). It ignored and alienated the moderate democrats whose votes were needed to secure passage of reform legislation. By words and deeds, it strengthened the hand of radicals in the democratic camp. The worst example was a white paper that China issued in June 2014 that gave radicals, who just then were losing influence, a new lease on life.

The democratic camp’s role

The democratic camp was not blameless by any means. Its main handicap was a lack of unity and leadership. Democrats were generationally divided over strategy and tactics. Should they try to improve the government’s proposal or reject it out of hand? How radically should opposition be expressed: peaceful assembly in line with existing norms, Gandhi-style civil disobedience, or something more extreme? In the end, young people preemptively mounted a civil disobedience campaign, but were not willing to surrender themselves to arrest. Their occupation of major transportation thoroughfares alienated the public, and by the time they successfully occupied public spaces, they lacked an exit strategy.

Moreover, democrats did not keep their eye on the ball about what sort of reform would be “good enough.” The radical wing of the democratic camp sought a wide-open approach to nomination where a tiny proportion of registered voters could nominate a candidate. They should have known that Beijing could not accept that—or they did know and didn’t care. More moderate types understood—correctly, I believe—that an acceptable outcome was creating space for a genuinely competitive election within the nominating process in which a qualified democratic candidate could get on the final ballot. Once on the ballot, a democrat had a good chance of winning because a clear majority of Hong Kong voters seemed to support the democrats. But the radicals held the balance of power within the democratic camp, and they would rather fight than win.

The ultimate irony was that the proposal that the Hong Kong government submitted to LegCo in April 2015 did, in fact, create a narrow pathway to such a competitive election. Essentially, the proposal allowed consideration of a range of “pre-candidates,” from whom the final candidates would be picked. The process would be transparent, so the public would know the policy views of each pre-candidate, and public opinion polls would show their relative popularity. Clearly, pro-Beijing members of the nominating committee on paper would have the votes to screen out any democratic pre-candidate. But if the democrats were strategic and put forward one popular moderate with centrist policy views and public prestige (such people do exist), it would be politically difficult for the nominating committee to reject him or her. Beijing understood the implications of this proposal, but it was voted down anyway. Ultimately, the reason was not the content of the reform proposal, but the deep mistrust that existed between democrats and Beijing, and, just as important, the mistrust between moderate and radical democrats. Radicals intimidated moderates into casting “no” votes.

Ultimately, the reason was not the content of the reform proposal, but the deep mistrust that existed between democrats and Beijing, and, just as important, the mistrust between moderate and radical democrats.

What Was the Role of the United States?

Washington was actually in an awkward position throughout this process. On the one hand, the United States generally supports democratization everywhere. On the other hand, it acknowledges and accepts that Hong Kong is a part of China and that the Basic Law is the city’s constitutional document. And it has other interests in Hong Kong, such as business and law enforcement.

Complicating matters was the practice, as noted above, by PRC propagandists to make repeated and totally false allegations that the United States was the “black hand” behind efforts in Hong Kong to radicalize the struggle over electoral reform. The communist press in Hong Kong worked overtime to create “evidence” to support its allegations about American subversion. Such allegations would be ludicrous if they were not repeated incessantly, but there is some reason to infer that policymakers in China actually believed them. The implication for U.S. policy was that if Washington overtly supported the democratic camp in words and deeds and opposed Beijing on the design of the chief executive elections, it would only strengthen Chinese beliefs in American perfidy.

To his credit, President Obama raised the issue with President Xi Jinping when they met bilaterally in Beijing during the 2014 APEC meeting. At their joint press conference after the meeting, Obama said that he had been “unequivocal in saying to President Xi that the United States had no involvement in fostering the protests that took place there; that these are issues ultimately for the people of Hong Kong and the people of China to decide.” But the propaganda attacks continued.

The Obama administration was subtle—and I think skillful—in stating where it stood. For example, as the Umbrella Movement began, the White House released a statement that in effect did the following for U.S. policy:

- Reaffirmed the political rights that the Basic Law conferred to the Hong Kong people.

- Urged each side in the struggle to share responsibility for exercising proper restraint.

- Respected both Beijing’s right under the Basic Law to set certain electoral parameters and the Hong Kong people’s political desires.

- Supported stability and prosperity in Hong Kong, but believed that those depend on an open society, maximum autonomy, and the rule of law.

- Asserted that the legitimacy of the chief executive in Hong Kong would be greatly enhanced if the goal instituting universal suffrage elections was fulfilled and if “the election provide[d] the people of Hong Kong a genuine choice of candidates that are representative of the peoples and the voters’ will.” In fact, Washington supported a genuinely competitive election.

Even if Washington wished to play a more active role in support of democracy and was willing to bear the consequences for that, there was a practical problem. That is, the democratic camp, which presumably Washington would be supporting, was seriously divided over goals, strategies, and tactics. Would it have been in our interest to get in the middle of an internecine struggle, one in which the mistrust between moderates and radicals was almost as bad as the mistrust between democrats and Beijing?

There were signs in late 2014 and early 2015 that Congress might pass a revision to the U.S.-Hong Kong Policy Act, but that has not come to pass. Congress on a year-by-year basis has recently required that the State Department issue a report on Hong Kong developments. That is a good thing and should be continued, because it shows that Washington is watching.

Although I believe that the U.S. executive branch threaded the needle well over 2014 and 2015, a more activist approach may be required going forward. That is because there are signs that China is not just nibbling around the edges of the political freedoms that it granted Hong Kong in its own Basic Law, but is in fact acting to restrict those liberties. The clearest example was the detention of a minor local bookseller in Hong Kong by agents of the Chinese regime—a clear violation of the Basic Law. Another example is requiring candidates running for the Legislative Council to make written anti-independence pledges that amount to restrictions of their freedom of speech. If it becomes indisputably clear that Beijing is intent on restricting the freedoms that it granted in the Basic Law and if the Hong Kong government and courts cannot block those moves—as I hope they would try to do—then the United States and other like-minded countries should voice strong objection and elevate the salience of the Hong Kong issue in their relations with Beijing. (In the recent September 4 legislative elections, the democratic forces improved their political position, demonstrating that the public rejected the conduct of Beijing’s Hong Kong policy. The downside was that the anti-establishment camp was more divided than ever.)

Implications

When it comes to promoting democracy more generally, the Hong Kong case is somewhat sui generis. It is a part of the People’s Republic of China, an increasingly authoritarian, communist system. China wrote the Basic Law in such a way that vested most local power in the hands of people who would not challenge its interest in control. It is and will remain Hong Kong’s sovereign. The United States had accommodated to these arrangements when they were put in place in the early 1990s (as had the United Kingdom, which, as Hong Kong’s sovereign then, negotiated the general terms of the city’s transition to Chinese rule). Washington would have been hard pressed to reverse these fundamental, long-standing decisions.

For a couple of decades now, Hong Kong has had features that predisposed it to a democratic transition. Beijing accepted that the city would have the rule of law and civil and political rights, which Hong Kong people have used to push for political change. Social and economic modernization, which generally sustain a democratic system, had already occurred before the 1997 reversion. The inequality that toxifies today’s politics is a fairly recent phenomenon. By and large, the public was pragmatic and even conservative in its political attitudes, and they demonstrated a maturity in the Legislative Council elections where one person, one vote was practiced (at least for half the seats). The city has a large number of very intelligent political thinkers who have discussed designs for full electoral democracy for decades now. As recently as a few years ago, moderate members of the democratic camp were prepared to work with Beijing to achieve a mutually acceptable compromise. This was an environment in which the United States could have played a supportive role with Hong Kong people doing most of the work to achieve a mutually acceptable compromise—if Beijing had decided to move on electoral reform much earlier than it did.

But by the time Beijing was ready to move, Hong Kong’s politics had changed in ways that made compromise far more difficult. The democratic camp splintered, with radicals gaining a dominant position and young people less willing to defer to their elders. Inequality deepened, expanding the grievances of the pro-democracy forces. Beijing became more paranoid about threats to national security, including imagined threats when it came to Hong Kong. “Getting to yes” became much more difficult and, on this occasion at least, impossible.

Democratic transitions do not work well when the authorities meet a political challenge with all-out repression and the democratic opposition attempts revolution. Democratic transitions work best when progressives in the regime and moderates in the opposition negotiate a “transition pact.” It is in those circumstances (e.g. South Korea, Taiwan) that the United States can be most effective. Regrettably, at a certain point in the Hong Kong debate over electoral reform, such a pact became, at least temporarily, impossible. Washington had the right declaratory policy but the receptivity of both Beijing and the democratic camp to American suggestions was missing. For the immediate future, however, the United States should vigilantly support protection of the freedoms that Hong Kong has and help oppose efforts by China to withdraw them.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).