This piece is part of a series titled “Nonstate armed actors and illicit economies: What the Biden administration needs to know,” from Brookings’s Initiative on Nonstate Armed Actors.

The research reported here was funded in part by the Minerva Research Initiative (OUSD(R&E)) and the Army Research Office/Army Research Laboratory via grant #W911-NF-17-1-0569 to George Mason University. Any errors and opinions are not those of the Department of Defense and are attributable solely to the authors.

The incoming Biden administration will need to quickly grapple with fundamental decisions about its Afghanistan policy. As I wrote separately, the choices it makes will depend on which decisionmaking framework it will adopt and on the priority it gives to different policy objectives in Afghanistan: a) a maximalist counterterrorism insurance posture; b) preservation of existing gains; or c) U.S. geostrategic objectives regarding China, and Russia, countering pandemics, and addressing global warming.

Each of these objectives has vastly different policy implications for the U.S. military presence in Afghanistan and the U.S. posture toward various Afghan actors, including the Taliban and the Afghan government.

Prioritizing maximum insurance against counterterrorism

The Biden administration can prioritize counterterrorism goals in Afghanistan, specifically countering al-Qaida and the Islamic State in Khorasan. This prioritization translates into two policy options: a maximum-insurance counterterrorism policy, or a normalized counterterrorism policy (more on the latter when I discuss geostrategic objectives).

The maximum-insurance counterterrorism policy centers on keeping a limited U.S. counterterrorism contingent in Afghanistan for a very long time, at least until a peace deal is struck. This approach assumes that despite the commitments the Taliban made in Doha in February 2020, the Taliban cannot be trusted to deny al-Qaida and other terrorist actors the capacity to attack U.S. and allied targets. The United States thus seeks to maintain a quick-strike force in Afghanistan.

Such a counterterrorism posture in turn requires that the Taliban relinquish its core objective of ejecting foreign troops from Afghanistan and subject itself to the vulnerability that the U.S. counterterrorism force could hit Taliban targets. The Taliban is extremely unlikely to concede to that, especially if the United States does not guarantee that it will accept a prominent role for the Taliban in the Afghan government, but rather seeks to minimize it.

Maintaining a counterterrorism-only force in Afghanistan would require the United States to stand by as the Taliban pounced on Afghan provincial capitals and took ever-more Afghan territory. The Taliban is unlikely to halt military action and agree to a permanent, comprehensive ceasefire, since its bargaining position in negotiations with the Afghan government and in many side negotiations with Afghan powerbrokers is directly a function of its military strength. The Afghan government, for its part, would not tolerate the collapse of its territorial control and would demand military assistance from the United States beyond funding its forces. Most of Afghan security forces remain dependent on U.S. and NATO forces, even for defensive operations.

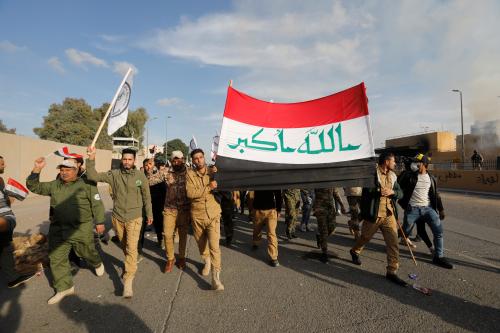

More likely, the United States would have to pursue such a maximum-insurance counterterrorism policy without an agreement from the Taliban. Yet within some months after May 2021 — by which time United States agreed to have withdrawn all of U.S. forces from Afghanistan in its deal with the Taliban — the Taliban would likely start shelling U.S. bases, perhaps with Iran’s assistance, and the United States would find itself on the cusp of a renewed war with the Taliban. The ground realities resemble Iraq’s — where pro-Iran Al-Hashd al-Shaabi militias regularly shell U.S. bases to drive the United States out — more so than Syria’s, where U.S. bases are in the territory of Kurdish allies and Russia has not yet decided to push the United States out of Syria. Prior to the Doha Agreement, Taliban regularly fired mortars at U.S. bases, and an armed actor in Afghanistan — likely the Islamic State in Khorasan — has now repeatedly fired truck-mounted missiles at U.S. targets.

Thus, the United States would have to maintain a counterterrorism foothold even as surrounding territories fell to the Taliban. If the U.S. wanted to slow the Taliban’s advance, it would need to increase troops beyond the 2,500 the Trump administration leaves in Afghanistan on January 19. However, restarting military actions against the Taliban and maintaining a U.S. military presence in Afghanistan also reduces incentives for the Taliban to uphold, however minimally, its Doha counterterrorism commitments. The Taliban has not severed its complex (including intermarriage) links with al-Qaida. But maintaining an open-ended U.S. counterterrorism force in Afghanistan could discourage the Taliban even from seeking to prevent al-Qaida terrorist actions emanating from Afghanistan — a less expansive but more important counterterrorism objective. Moreover, although the Taliban currently battles with the Islamic State in Khorasan, the Taliban could seek a détente with the group.

Prioritizing “preserving gains in Afghanistan”

Alternatively, the Biden administration could prioritize preserving the gains of the two past decades in Afghanistan, including the existing Afghan constitution, democracy, and human rights, including of minorities and women. In essence, this policy still seeks to defeat the Taliban — if not on the battlefield alone, then at the negotiating table. It can be prosecuted through two different means, both strongly welcomed by the Afghan government.

First, the United States could again dramatically increase U.S. military presence in Afghanistan and absorb the geopolitical, foreign policy, and domestic costs of doing so. But since 150,000 U.S. and NATO forces failed to defeat a then-much weaker Taliban a decade ago, there is little prospect a smaller U.S. and allied force would defeat a much stronger Taliban now. Nor has governance in Afghanistan improved enough to deprive the Taliban of popular support.

Alternatively, the United States could attempt to adopt a limited, but an open-ended, military presence that persists until the Taliban agrees to a peace deal that the United States and the Afghan government like. This would mean minimal changes to Afghanistan’s political dispensation and a token presence of Taliban in the Afghan government.

The “preserving gains” approach hinges on the hope that once the United States discards the May deadline for its military withdrawal, the Taliban will — for some reason — give up its strategic objectives and ignore its internal cohesion imperatives. That’s unlikely. For several years, the Taliban has been intensely pounding Afghan security forces and weakening them. The latter are continually, if slowly, losing battlefield and psychological ground. At best, this policy thus slows down the degradation of Afghan security forces and the rate of Taliban’s military gains. This is a repeat of the “hoping and praying” approach from 2015-2017, that somehow something will change on the battlefield and the Taliban will suddenly start making enough strategic mistakes to destroy itself.

Under this policy, the Taliban may walk away from negotiations for years to come. Meanwhile, this prioritization inflates the negotiating demands of the Afghan government. As long as the United States stays until a “good” peace deal is reached, the Afghan government bears few costs if negotiations collapse or drag on, and may easily prefer either. With Washington propping up the government, there are few incentives to make significant concessions to the Taliban or other Afghan powerbrokers rocking the government with their parochial ploys.

Even if negotiations don’t collapse, the Taliban may resort to shelling U.S. bases, or the United States may start hitting Taliban targets and drive it back to negotiations with reduced demands. Like in the maximalist counterterrorism policy, the United States thus slips back into open-ended fighting. Again, the Taliban loses incentives to uphold at least some of its counterterrorism commitments.

More broadly, an open-ended military deployment will raise tensions between the U.S. and regional powers — China, Russia, and Iran — none of which wants a sustained U.S. military presence in Afghanistan (even though they welcome the U.S. distracted and bogged down). Nor do they want intensified civil war as a result of the United States simply washing its hands of Afghanistan. Nor do they want a return to a 1990s-type Taliban rule. What they do want is a coalition government in which the Taliban is constrained; at the same time, each has made its peace with the Taliban. If the possibility of an extended U.S. presence becomes real, those powers could intensify assistance to the Taliban or assorted Afghan militias, or pressure Pakistan to deny the United States access to Afghanistan. That, in turn — Pakistan’s denial of U.S. access to its and ground lines of communication — would make U.S. and NATO deployments in Afghanistan struck. We don’t want a situation where Washington must subordinate the rest of its relationship with Pakistan to maintaining the access, even as Pakistan is not doing more to get the Taliban to reduce violence against Afghan and, eventually again, U.S. forces.

Prioritizing U.S. geostrategic imperatives and an end to the war

Third, the Biden administration could prioritize U.S. geostrategic interests: competition with China in the Indo-Pacific, countering Russia’s nefarious activities around the world, and countering transnational threats like pandemics and global warming, all while seeking to end Afghanistan’s 40-year-old civil war. Tens of thousands of Afghans are currently dying annually.

This prioritization recognizes that the Taliban is ascendant in Afghanistan and that the United States does not have the capacity, at any reasonable cost, to reverse that trend, even with a sustained military presence.

The United States would accept that the Taliban will become a strong actor in the Afghan government and that the political dispensation in Afghanistan would change as a result. Despite the Afghan government’s strong opposition, this prioritization would mean that the United States moves toward a posture of greater neutrality toward the Afghan government and the Taliban. The peace that could result can assure that America’s primary and secondary objectives in Afghanistan (mitigation of counterterrorism threats and an Afghanistan not dominated by a hegemonic power or a hostile government) are met, and allow the United States to extricate itself from Afghanistan. The United States would seek to minimize losses to its tertiary interests of pluralistic and inclusive processes and human rights, women’s rights, and minority protections.

In this scenario, the United States could — and should — seek to negotiate with the Taliban over a short-term extension of U.S. military presence, such as through the end of 2021. It would emphasize to the Taliban that the purpose of the extension is to avoid more fragmentation of the civil war and provide a better foundation for a stronger and more stable Afghan state in which, the United States accepts, the Taliban will play a strong role.

With or without the extension, the United States would shape the Taliban’s negotiating demands, behavior, and rule through economic and diplomatic carrots and sticks. It would offer and deny economic and diplomatic aid, recognition, legitimacy, visas, and the cancelation of sanctions or imposition of new ones. The United States would condition its engagement with the Taliban and aid flows to a future Afghan coalition government on some inclusivity in governance and some preservation of human rights, including for minorities and women.

The Taliban wants international legitimacy and understands the need to sustain Western aid flows to avoid a 1990s-like economic meltdown. But the Taliban has very little understanding of what is required to run a country in the 21st century, nor does it fully understand donor aid conditionality. Thus, the shaping strategy includes educating the Taliban about modern governing systems. This strategy will not result in the Taliban embracing democracy and civil liberties. Significant changes to Afghanistan’s political system can be expected. The changes in its formal constitution, and the persistence of informal practices, would make Afghanistan’s government system resemble various governments in the Middle East and Central Asia — not bastions of democracy.

U.S. counterterrorism policy, too, would become normalized. The United States would seek principally the Taliban’s cooperation in countering plots from al-Qaida and other terrorists against the United States and its allies, not necessarily the Taliban’s expulsion or handover of all al-Qaida members. This policy thus maintains incentives for the Taliban to comply with its Doha counterterrorism commitments. But the United States would center its Afghanistan counterterrorism policy on means other than U.S. military forces: off-shore strikes, perhaps the stationing of a counterterrorism strike force in Pakistan, U.S. homeland defenses and asset hardening, and even pro-U.S. militias (troubled and fraught as such policy is).

This policy accepts significantly scaled-down U.S. objectives and requires Washington to swallow not just one, but several bitter pills. Such a policy would be deeply disappointing to many urban Afghans. But it is a realistic policy that prioritizes U.S. important strategic priorities and domestic objectives.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

In Afghanistan, different priorities means vastly different policies

January 15, 2021