This piece is part of a series titled “Nonstate armed actors and illicit economies: What the Biden administration needs to know,” from Brookings’s Initiative on Nonstate Armed Actors.

Once the Biden administration enters office, it will begin implementing the first U.S. “Strategy to Prevent Conflict and Promote Stability,” released on December 18 and originally called for in the 2019 Global Fragility Act. This will include selecting priority countries and regions to receive $1.1 billion in foreign assistance over 10 years on conflict prevention and stabilization, and then overseeing strategy implementation in these locations.

To maximize the strategy’s efficacy, the U.S. government must ensure the implementation plan has a clear goal and theory of success to achieve it — and addresses pressing challenges, including the fallout from COVID-19 and spoilers’ efforts to subvert peace. The pandemic has strained services and governing systems in already-fragile contexts, giving rise to a bevy of reinforcing challenges, from displacement and violent extremism to economic deprivation and democratic backsliding.

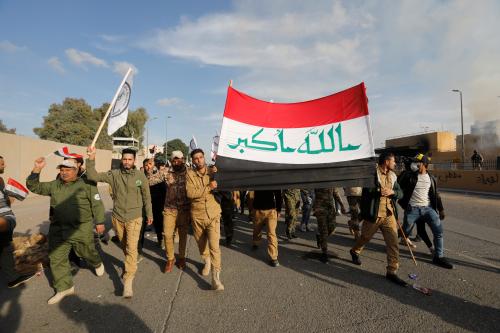

Chief among these challenges will be nonstate armed actors that are an entrenched source of violence in nearly every potential priority country. From the Northern Triangle to East Africa, wherever the Biden administration decides to focus, it will face this problem set.

Nonstate armed actors like militants, rebel groups, terrorists, and militias contribute to instability by threatening the state’s hold on territory, offering governance alternatives that defy government legitimacy, enabling illicit economies, and serving as proxies for Russia, China, and Iran.

In some cases, nonstate armed actors drive instability that negatively impacts U.S. interests; in others, they might help reduce violence and be part of a solution to resolving armed conflict.

Nonstate armed actors are proliferating — 44% of armed conflicts across the world have between three and nine opposing forces, and 22% have more than 10. In Colombia, the National Liberation Army (ELN), dissidents with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), criminal gangs, and neo-paramilitary groups compete for political power and disrupt volatile security dynamics; in Sudan, the absence of two powerful rebel groups in the peace process complicates an already-fraught democratic transition; and in Libya, political power is concentrated in armed militias through a myriad of parallel institutions.

Recognizing this challenge, the new fragility strategy calls for “reduc[ing] the destabilizing impact of nonstate armed actors” as a key objective. However, the document provides few details on how it will accomplish this aim. As the Biden administration moves to implement the fragility strategy, how should it approach working with nonstate armed actors as a potential means to maximize efficacy of conflict prevention and stabilization? And what, if any, broader changes should it make to U.S. policy related to engaging such actors? Here, we explore these questions and offer five recommendations.

Rules of engagement: Constraints, gaps, and trade-offs

Nonstate armed actors — at a global scale — show few signs of waning in scope and activity. They will continue contributing to instability that hinders U.S. national security interests.

Because of this, the new U.S. fragility strategy smartly asserts that, to ensure a long-term solution, the U.S. must address priority causes of conflict and fragility to include supporting stronger and more inclusive governance systems. But this will take time and, in the short term, the pressing need to neutralize or at least mitigate threats from nonstate armed actors should not be overlooked.

The current U.S. approach to nonstate armed groups is undoubtedly shaped by the last two decades of counterterrorism laws and operations. The U.S. counterterrorism framework fails to reflect the complexity of current realities, where government actors may act like armed groups and nonstate armed actors may behave like governments. This extends not only to U.S. direct engagement, but indirect as well, which can signal (through announcement of bounties on specific individuals, for example) that partners should avoid engaging specific terrorists or nonstate armed actors instead of employing diplomatic measures to de-escalate or mitigate the problem. Counterterrorism regulations also deter risk-avoidant funders from providing much-needed assistance, due to arduous processes and adverse consequences associated with the possibility of providing material support to terrorist groups.

Three factors affect U.S. engagement with nonstate armed actors and the short-term options a Biden administration has available for dealing with this problem set.

First, there is dissonance between security operations, development policy, and counterterrorism laws. The concept of partnering with nonstate armed actors is not new — the U.S. and other Western allies frequently employed this approach during the Cold War and encountered many pitfalls, most notably in Afghanistan. Today, the U.S. works “by, with, and through” such armed actors to counter terrorism in places like Mali, Libya, Syria, and Somalia where host governments are unwilling or unable to partner with the United States. Although these operations may help advance U.S. interests, they often yield mixed results, harm civilians, and risk perpetuating cycles of violence if partnerships are not well-crafted.

Meanwhile, U.S. law limits policy options for engaging nonstate armed actors designated as terrorist organizations or with links to them, including defectors. While understandable in principle, the regulation has hampered some U.S. stabilization efforts. For example, in Nigeria, the U.S. government’s designation of Boko Haram as a foreign terrorist organization has resulted in the requirement for approval prior to providing assistance to any individuals formerly affiliated with Boko Haram — potentially undercutting efforts to facilitate defections. Although the U.S. has provided new guidance on defections and disengagement, such efforts are constrained by existing laws and regulations.

Second, the U.S. prioritizes a state-centric approach to engagement. Working through the central government is in line with an international order organized around states and their internal sovereignty. In some cases, the United States understandably avoids bypassing the central government because its buy-in ensures foreign assistance avoids delegitimizing the state. But this capital-focused approach has limitations. When the government may be predatory and perpetuate conflict, and is thus unwilling to engage, however, the United States has few options.

Third, the Biden administration may be limited by the fact that the United States does not have a policy framework outlining parameters to determine which nonstate armed actors are acceptable to engage, whether through diplomacy or support. The 2018 Stabilization Assistance Review defines U.S. stabilization as a “political endeavor” to create conditions where “locally legitimate authorities and systems” can peaceably manage conflict. Yet the United States has not developed a definition of local legitimacy, metrics for measuring it, or other criteria to consider when deciding whether to engage — for instance, whether such armed actors support democracy as the desired form of governance.

Absent such a framework, U.S. officials rely on their analysis and intuition to formulate policy and implementation approaches on the fly, the results of which are sometimes far removed from the reality on the ground.

Recommendations for calibrating the U.S. approach to nonstate armed actors

Highlighting the above policy gaps is not to downplay the problem’s thorny and complicated nature or associated security and political risks it poses to any administration. On one hand, embracing nonstate armed actors — even at a limited level of engagement — carries significant risk due to their shifting levels of violence, political agendas, and often fragmented organizational structures. On the other, failing to engage nonstate armed actors can sometimes undermine development efforts and inflame the root causes of conflict by marginalizing key actors.

The U.S. record on partnerships with nonstate armed actors is fraught, but there are only least worst options for addressing the role of nonstate armed actors in violent conflict. To avoid the pitfalls of previous partnerships and maximize the global fragility strategy’s efficacy, the Biden administration should do five things.

First and foremost, the United States should review and refine existing legal frameworks that inform its approach to nonstate armed actors. To avoid securitizing much-needed development assistance while also balancing accountability for human rights violations, the new administration should critically examine the strengths and gaps in these frameworks and make necessary revisions. Addressing legal ambiguity will help prevent uneven interpretation, particularly if the U.S. specifies the exact meaning of “engagement” or “support” in counter-terrorism regulations that shape development assistance. The U.S. should also establish a process to remove terrorist designations from groups that have signed a peace agreement and committed to demobilization, such as the FARC. In short, the U.S. should explore expanding its willingness to talk with nonstate armed actors, collaborate with them on a limited basis to stabilize conflict affected areas (through initial security and COVID-19 healthcare provision, for example), and facilitate inclusive engagement through political means in efforts to establish off-ramps and enable defections, while ensuring oversight and accountability.

Second, the United States should develop guidance that defines parameters for engaging nonstate armed actors, to include a definition of “legitimacy,” criteria for considering their membership composition, past crimes, objectives, and whether they align with stability and U.S. interests. The parameters should build on local understanding and acceptance of legitimate governance and political conduct, as well as consider the relationships between a nonstate armed actor, the government, and the population it represents. The guidance should assess the extent to which nonstate armed actors exercise governing authority and, where possible, understand the nature of governance — including views and actions toward inclusion and human rights. Above all, the parameters should center on protection and human security to ensure a balanced and impartial approach.

Third, in crafting country implementation plans for the fragility strategy, the U.S. should outline different scenarios, methods, and plans for engagement with nonstate armed actors and understand their benefits and consequences. If deemed appropriate, the U.S. should start with lower-risk engagement, understand the results, and adapt accordingly. For example, this could involve measuring the results of expanding political participation with citizens and nonstate armed actor members alike, taking stock of its effectiveness and then informing broader U.S. engagement and accountability measures based on the results. As part of this effort, the U.S. could employ a conditional approach to providing political, economic, and security assistance to establish clear parameters and exercise caution.

Fourth, where nonstate armed actors are demobilized and the reintegration period has been initiated, the United States should provide these groups the resources and skills to govern effectively and engage in political outlets. Even where the United States cannot directly engage or support such groups, it could help partner governments craft strategies that include them, should they meet criteria noted in the criteria recommended above. For example, in the Philippines, the former insurgent group Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) is now part of the transition authority of a new autonomous region. Amidst rising expectations, inexperience, and new threats from violent groups, technical assistance on effective governing practices is sorely needed. Similarly, as Colombia grapples with ongoing violence, the FARC political party — established in 2017 after the peace agreement — needs support in adopting peaceful and democratic norms when crafting their policy platform.

The role that such actors play in exercising predatory behavior and perpetuating fragility cannot be overlooked and should trump whatever benefit to U.S. national security might come from engaging them.

Finally, the United States should develop mechanisms to monitor and enforce accountability for human rights violations by nonstate armed actors. The role that such actors play in exercising predatory behavior and perpetuating fragility cannot be overlooked and should trump whatever benefit to U.S. national security might come from engaging them. This includes raising awareness of international humanitarian law, linking principles to local norms, and outlining concrete ways this would be enforced. To establish a culture of human rights and inclusion, the U.S. should develop a robust accountability framework that continuously monitors the long-term effects of engagement with nonstate armed actors. In so doing, it should not only demand that human rights standards be met among violent extremist groups, insurgencies, and state actors, but should also monitor and preserve the protection of communities, defectors, and affiliates of such groups.

Seize the moment

The Biden administration has an unparalleled opportunity to meaningfully reduce fragility in the places that matter most for U.S. interests. In so doing, it should reexamine its approach to nonstate armed actors and continue working to address the source of these groups in the first place: predatory politics and ineffective governance that, combined with other grievances, pushes individuals to pick up arms.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Want global stability? Modify the U.S. approach to dealing with nonstate armed actors

January 15, 2021