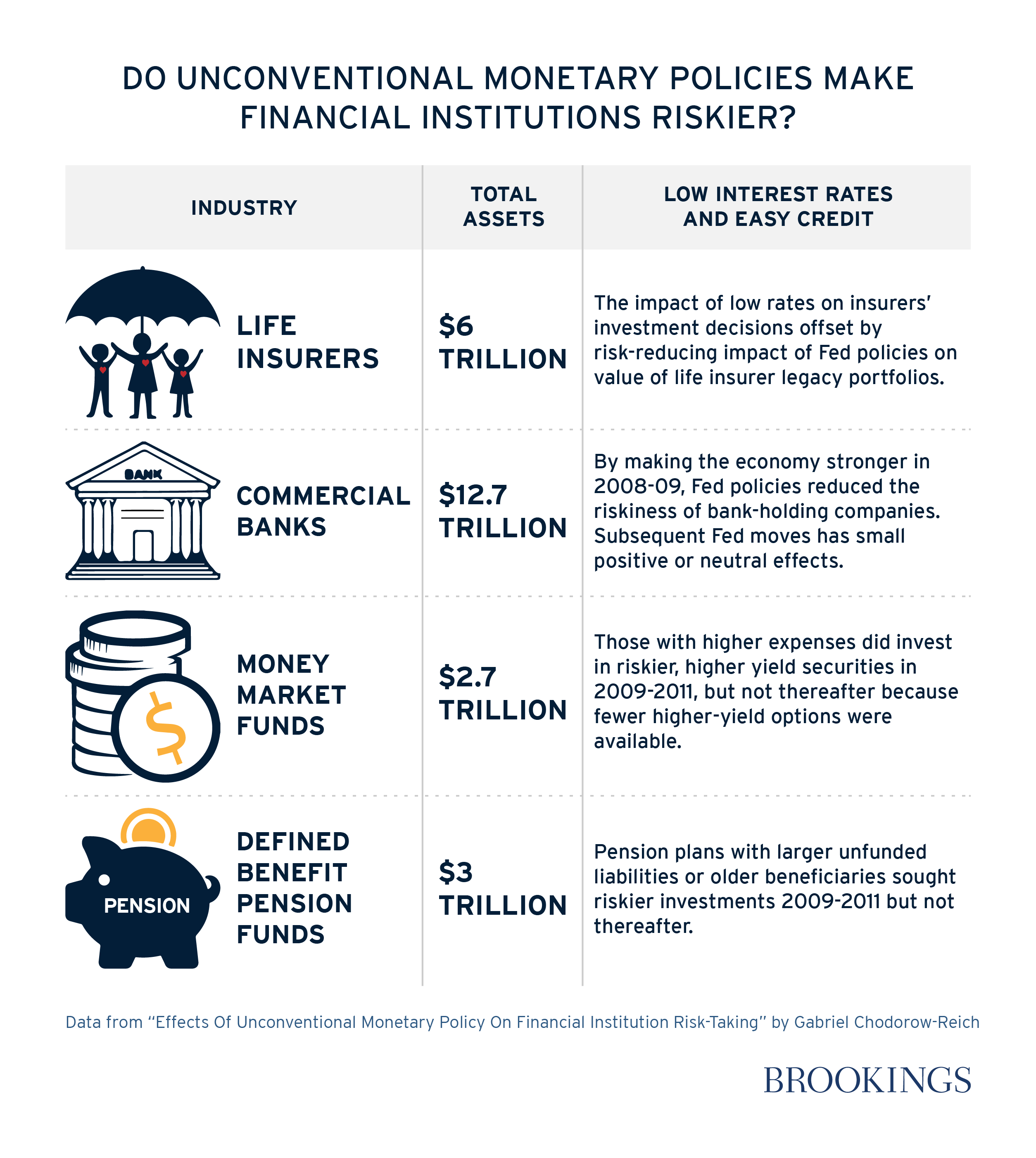

But Fed policies did prompt higher cost money market mutual funds to take on more risks in 2009–2011, though not subsequently, and defined benefit pension plans with larger unfunded liabilities or an older average age of beneficiaries to seek riskier investments after 2009, Gabriel Chodorow-Reich of Harvard University finds in “Effects of Unconventional Monetary Policy on Financial Institutions.”

Chodorow-Reich explains that the Fed’s recent low interest rate policy may have prompted financial institutions to “reach for yield,” that is, to make riskier bets than they otherwise would in search of greater returns. As then Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke noted in May 2013 Congressional testimony: The Fed’s policy-making Federal Open Market Committee takes “very seriously…the possibility that very low interest rates, if maintained too long, could undermine financial stability. For example, investors or portfolio managers dissatisfied with low returns may reach for yield by taking on more credit risk, duration risk or leverage.”

But Chodorow-Reich notes that those same Fed policies also make the overall economy stronger, boosting the value of financial institutions’ portfolios and making them less risky. To determine which effect is stronger, he examines the impact of Fed policy on four categories of financial institutions – life insurers, large commercial banks, money market mutual funds and defined-benefit pension funds. Collectively, they manage more than $24 trillion in assets.

Chodorow-Reich’s bottom line is: “In the present environment, there does not seem to be a trade-off between expansionary [monetary] policy and the health or stability of the financial institutions studied.” He notes, however, that there are other channels through which Fed policy may lead to unwelcome financial instability, such as abrupt changes in financial circumstances that lead asset managers to all sell assets at the same time.

Life insurers and commercial banks: Sustained low interest rates may cause life insurers to engage in riskier behavior, that is, to reach for yield. On the other hand, Fed policies raise the value of mortgages, bonds, and other assets held by life insurers, reducing their riskiness. To gauge the overall impact, Chodorow-Reich traces the reaction to Fed monetary policy announcements of the share prices, bond yields, and the cost of insuring debt in the credit default swaps market, of life insurers and bank holding companies.

He notes that the initial round of quantitative easing in 2008–09 had “a clear beneficial impact” on bank holding companies and especially on life insurers, and reduced perceptions of their riskiness. Their stock and bond prices rose, and the cost of insuring their debt fell. On March 18, 2009, for instance, when the Fed announced a $1.15-trillion expansion of its planned purchases of government and agency bonds and mortgages, every life insurer in the sample saw its stock price increase; the average price rose 4.0 percent, while the overall stock market, as measured by the S&P500 excluding financial firms, rose 1.5 percent. Shares of bank-holding companies rose 2.5 percent. The price of insuring the debt of four big insurers (Allstate, MetLife, Lincoln National and Prudential) fell; the same was true for seven of eight large banks, the exception being Citigroup. In other words, financial markets see unconventional monetary policy as making life insurers and banks less risky. Chodorow-Reich explains the especially large effect on life insurers by pointing out that billions of dollars of writedowns on their assets left many life insurers close to insolvency in early 2009, making policies that raised the value of their assets particularly valuable to them. Fed moves after 2009 had a more muted effect, but ranged from positive to neutral, according to his research.

Money market funds: Very low interest rates pose a challenge for money market mutual funds. To keep their investors earning a positive after-fee yield, many have waived management fees, creating a temptation to reach for yield, because each basis point in higher yield reduces the amount of fees the fund must waive. Chodorow-Reich finds that money market mutual funds with higher costs did buy riskier, higher yield securities in 2009–2011, but not thereafter. With so little difference in yields on assets in which money market funds are permitted to invest, there is now very little reaching for yield. He notes, though, that if higher-yielding securities become available again, perhaps the result of Europe’s sovereign-debt crisis, money market funds could, again, take more risks to boost returns.

Defined-benefit pension plans: Chodorow-Reich finds that private-sector defined-benefit pension plans with larger unfunded liabilities or with a large number of current beneficiaries relative to total plan participants did reach for yield in 2009 and the following couple of years, but he finds little evidence of that in 2012. As with banks and life insurers, the favorable effects of unconventional monetary policy on the stock market have improved the solvency positions of pension funds and therefore reduced the temptation to invest in riskier securities.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).