Widening geographic inequality in the United States has shifted federal policymakers’ attention to investing in “places” as well as “people.” On his first day in office, President Biden signed an executive order prioritizing support for underserved communities, including those in rural areas.

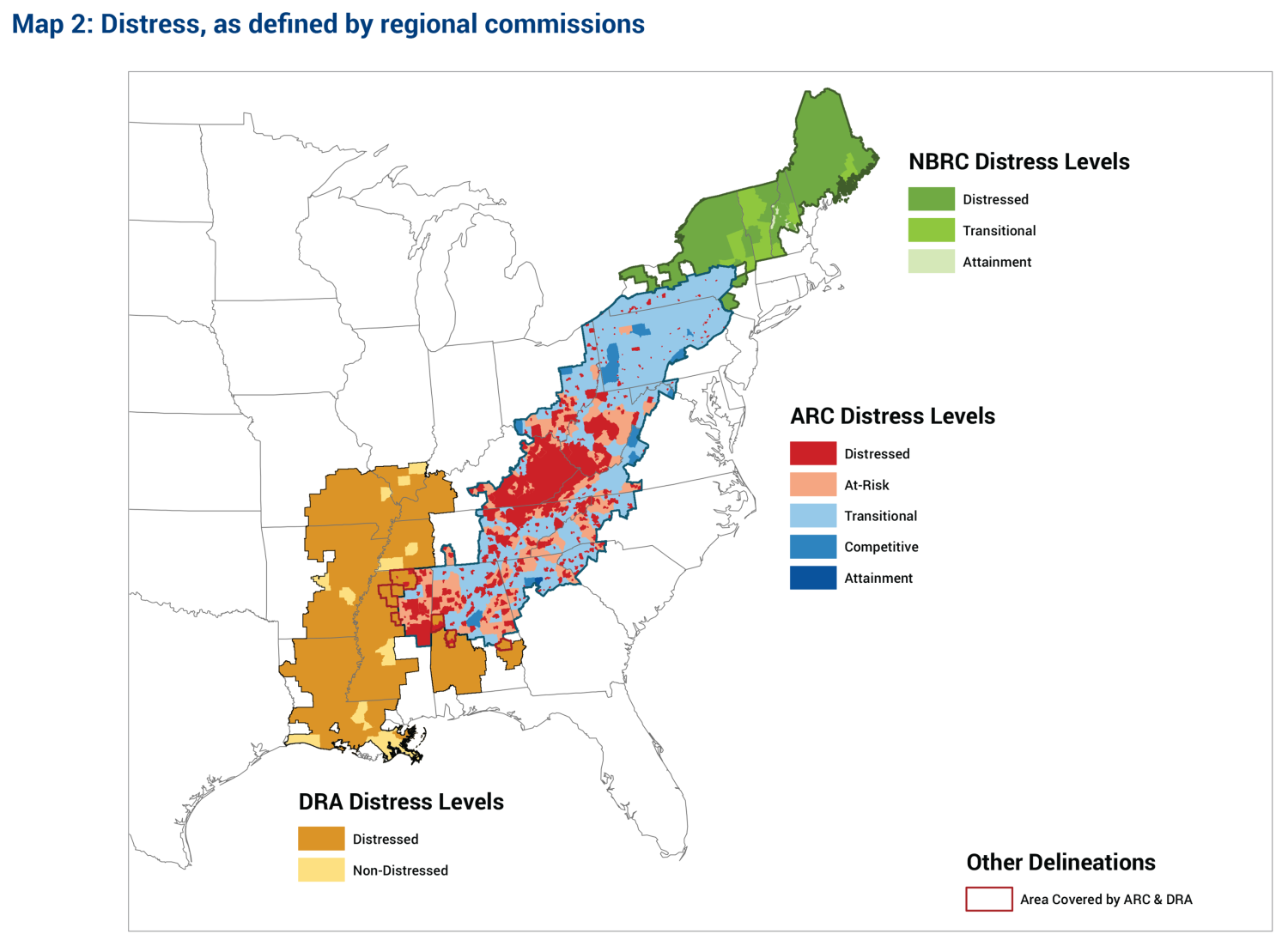

For each of the three active federally chartered regional commissions that serve more than one state—the Appalachian Regional Commission, Delta Regional Authority, and Northern Border Regional Commission—the authorizing legislation explicitly requires the commission to assess annually which places within their service area can be classified as “distressed,” and to spend at least half, but often more, of their grant resources in those places.123 Given the large proportion of rural places in their coverage areas, the use of “distress” by the commissions offers insights and lessons for reaching vulnerable rural communities.

Each commission defines distress differently, starting from the respective statutory requirements, balanced by internal analysis and capacity. Comparing their definitions illuminates the implications of different approaches and provides insights into the idiosyncrasies of designing methods for targeting specific types of communities.

Since definitions of distress are used to allocate funding and often determine eligibility and matching requirements, aligning the definition with the policy objective is of utmost importance.

Key takeaways from the examination include:

- Classifying communities along a continuum of “distress” enhances targeting.

- Using clear cutoffs or multiple criteria can also help hone in on the most affected communities.

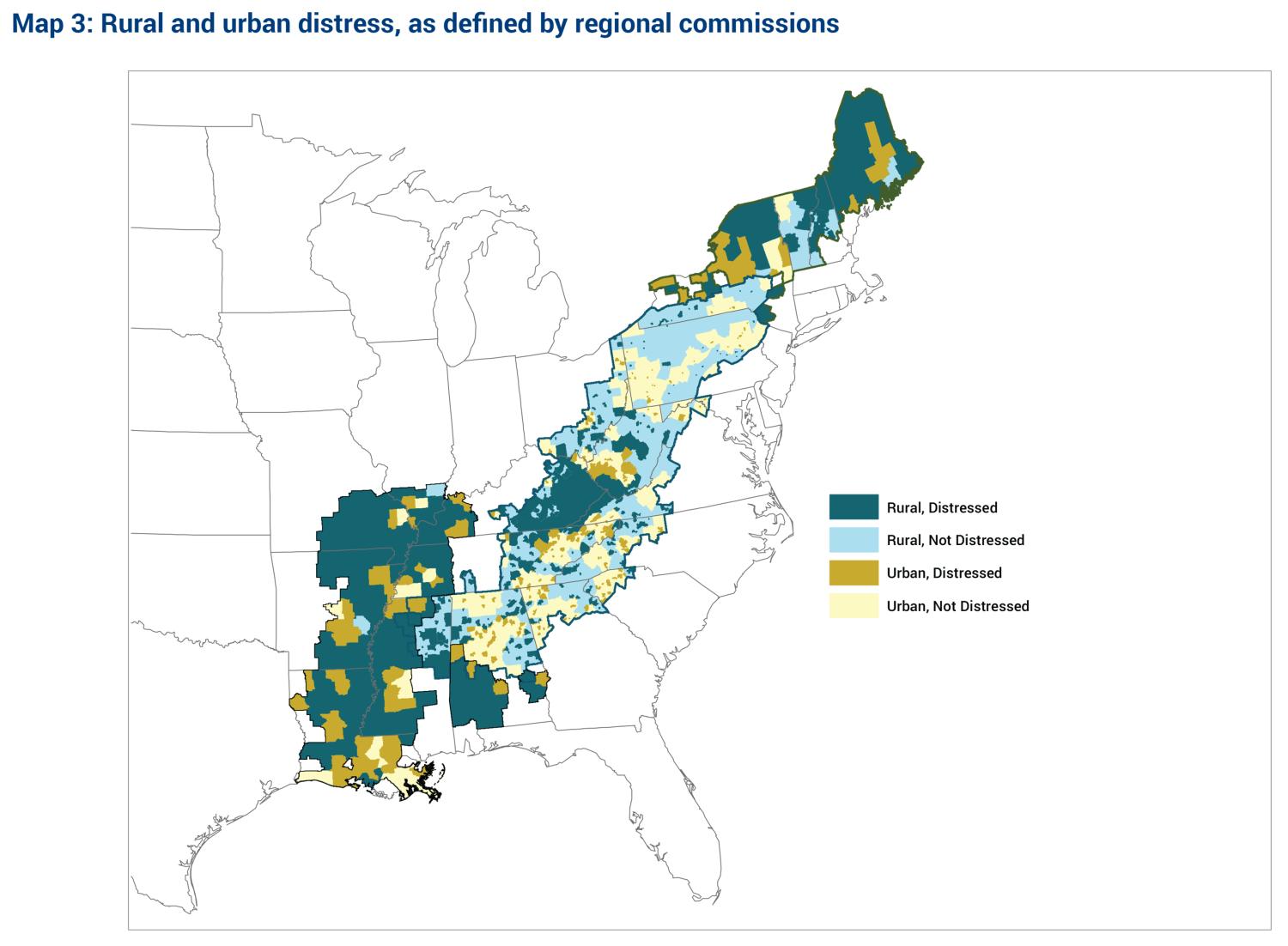

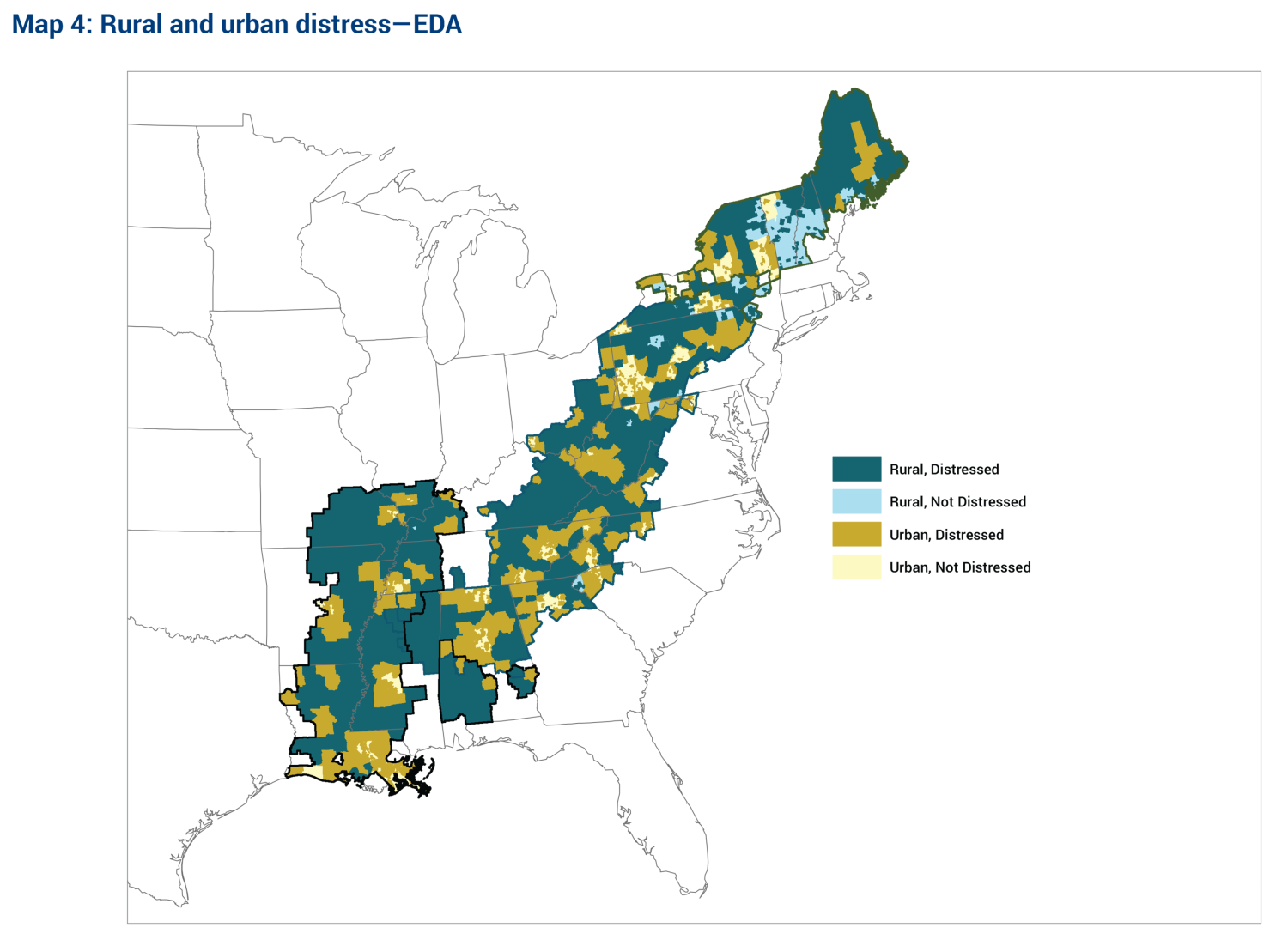

- Differentiating among communities below the county level reveals variations that, if unnoticed, can otherwise disadvantage rural areas.

- Utilizing nuanced distress designations can lower barriers to access and improve program success.

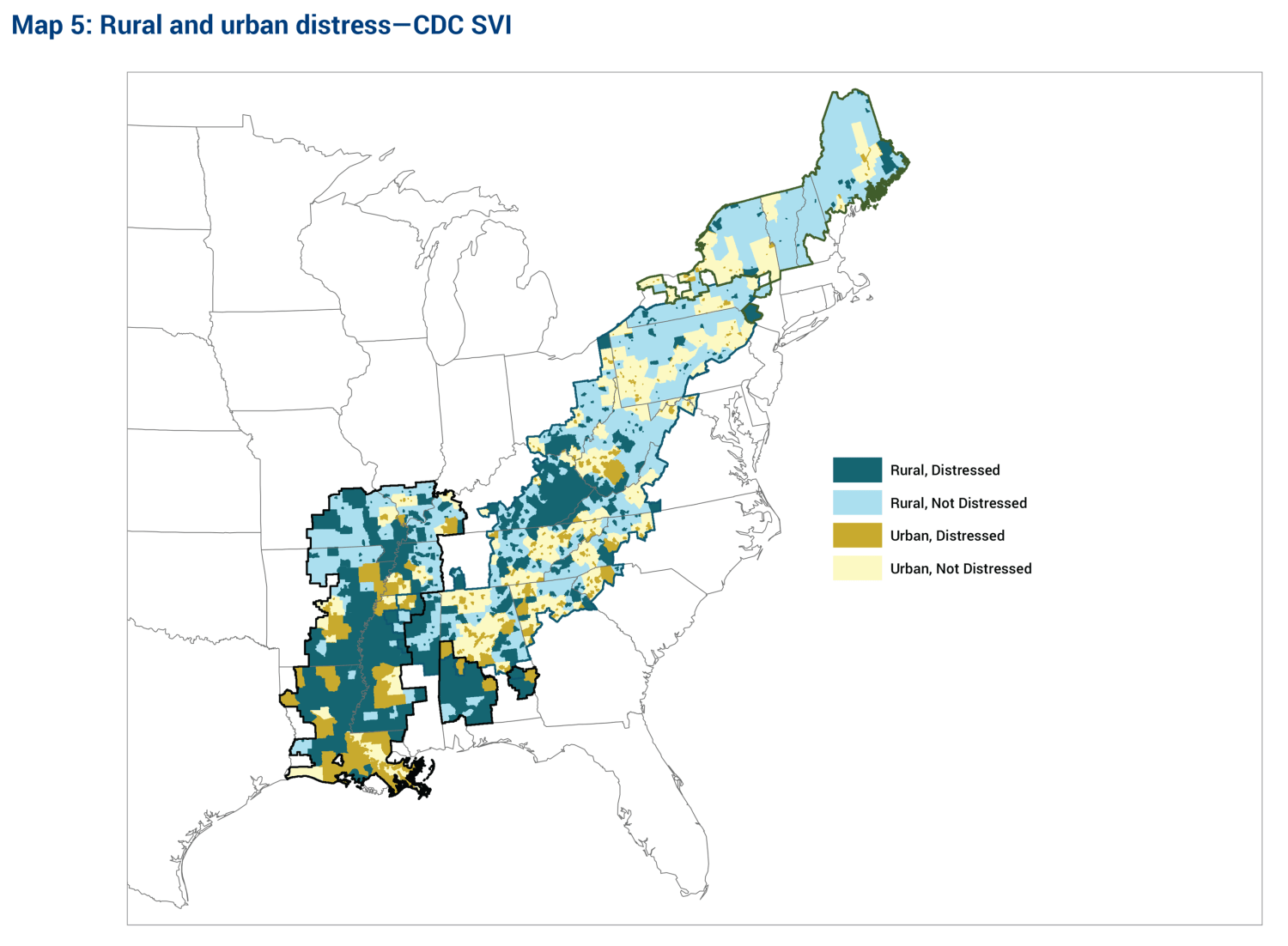

- Looking beyond traditional economic indicators may enable a more comprehensive sense of a community’s well-being and resilience.

- Forward-looking indicators can capture vulnerability and risk, which may help forestall economic decline and dislocation.

- Third-party innovations in measuring distress and community well-being can offer helpful insights for programmatic effectiveness, but risk adding confusion.

- Qualitative methods can add important elements and nuance to the state of a community’s agency, resilience, and well-being.

We propose three considerations to help refine the meaning and use of “distress” and improve the effectiveness of rural policy:

1. Develop a normative framework for defining distress in order to be explicit in identifying and matching policy objectives to definitional characteristics and uses. While undertaking this analysis, we came to prefer definitions that offer the most specific differentiation among communities and go below the county level, as they improve the likelihood of the funds being directed to the most distressed places. Yet we recognize that is not the sole policy objective for many programs. A normative framework would help policymakers weigh the importance of various factors and take into account the considerations posed by guiding questions.

2. Improve transparency about the specific communities that are receiving funds and their defining characteristics, as well as the implications of describing distress in a particular way. Clear, accurate, and easily accessible information is all too often unavailable to determine which communities are accessing and benefiting from federal resources. Making such data widely available will improve our understanding of the extent to which resources of specific federal programs are reaching certain types of communities. This would be an important step forward in ensuring program effectiveness.

3. Engage potential recipients to learn from their experiences with different distress definitions and eligibility requirements and to get their guidance on the extent to which particular indicators and approaches meaningfully reflect the realities of their communities. Definitions of distress, in essence, create a template by which communities are forced to describe themselves as they seek the partnership of the federal government in improving their well-being. Recognizing the importance of these definitions in shaping a community’s identity and considering the extent to which they capture the full measure of a community’s reality will deepen their utility and sharpen their accuracy. If current measures are not reflecting the reality on the ground, then such engagement will help identify what other factors can be included.

Download the full policy brief

-

Footnotes

- Appalachian Regional Development Act, 40 U.S.C. (2021), https://www.arc.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Appalachian-Regional-Development-Act-Amended-2021.pdf.

- Distressed counties and areas and nondistressed counties, 7 U.S.C § 2009aa–5 (2022), https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/7/2009aa-5.

- Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008, Pub. L. No. 110–234, 122 Stat. 923 (2008), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-110publ234/pdf/PLAW-110publ234.pdf.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).