As the 2020 election showed, America’s political polarization is as deep as ever. But the differences among America’s metropolitan and small-town communities are not always ideological, but informed by decades of divergence in prosperity between the nation’s booming cities and its rural areas.

As rural communities adapt to 21st century shifts in the national and global economy, demographics, and climate, the fallout from COVID-19 and the attention to racial injustice adds new urgency to their situation. A recovery from COVID-19 that strengthens America’s economic resilience and prosperity, reduces its social vulnerabilities, and addresses long-standing racial and social inequities will require policies that enable more diverse places—as well as people—to thrive.

Rural America boasts a rich diversity of identity, employment, culture, and experiences. People of color comprise 21 percent of the rural population; rural areas have higher self-employment rates than urban counterparts; and rural assets will be central to modernization and transition underway in several of the nation’s key industries.12 Yet rural people and places also face unique vulnerabilities: Their recovery from the 2008 recession was incomplete before COVID-19 hit, and they lag other areas on indicators of poverty, health, and education.34 Many distressed rural communities are those where racial inequities dominate.

In a nation where long-term poverty and economic distress concentrate disproportionately among people of color in rural areas, it is impossible to disentangle rural development from efforts to promote economic and racial justice. It is time to consider geographic equity as a key element of a long-term equity agenda.

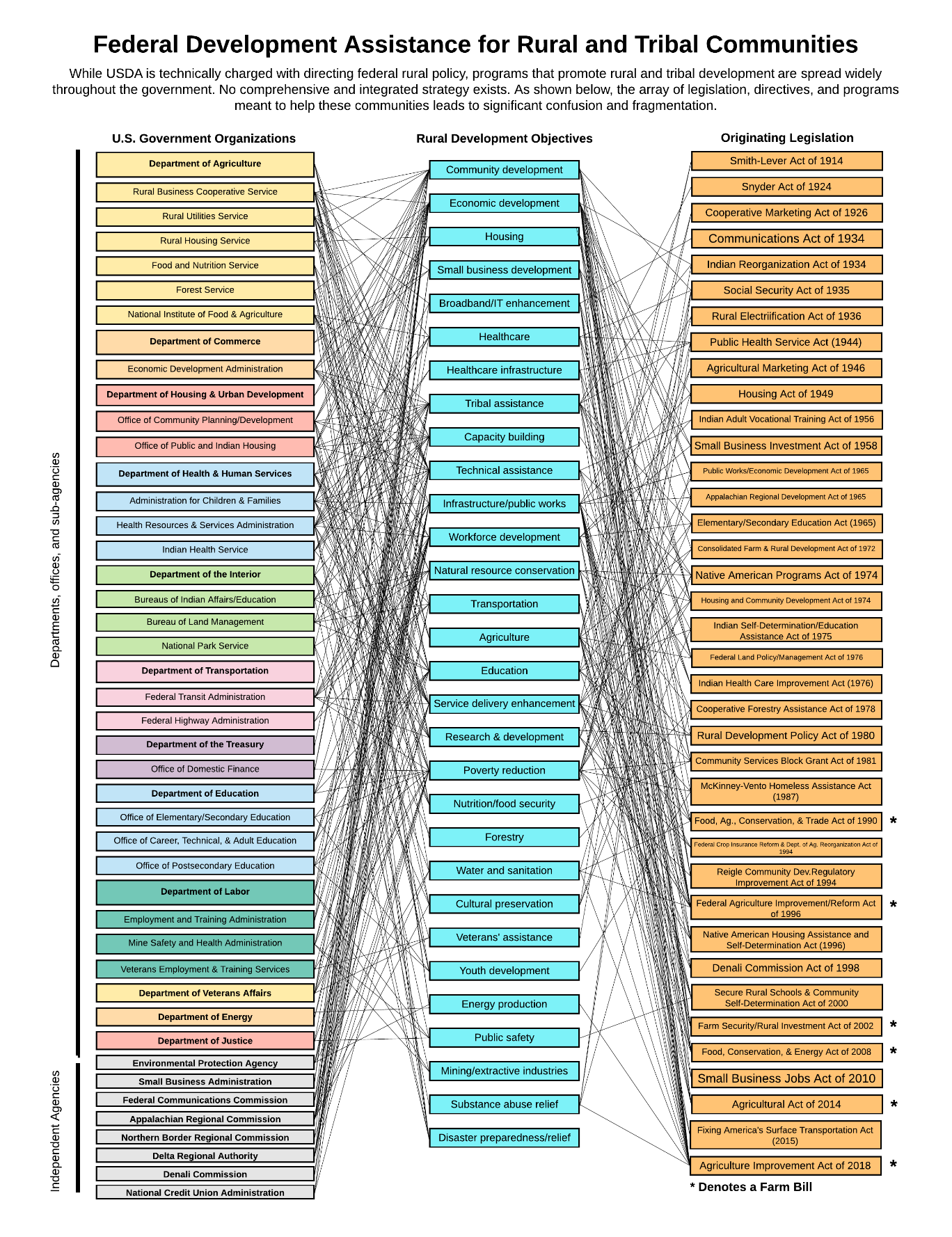

Federal assistance for rural development is outdated, fragmented, and confusing

The federal programs and tools available today to promote rural economic and community development serve as a reminder of active federal involvement in the 20th century. Yet they are outdated, fragmented, and incoherent.

Over 400 programs are open to rural communities for economic and community development, spanning 13 departments, 10 independent agencies, and over 50 offices and sub-agencies. A total of 14 legislative committees have jurisdiction over the authorizing legislation for these programs. While the U.S. Department of Agriculture is charged with coordinating federal rural policy, these programs go far beyond its authority—similarly, today’s rural policy must go far beyond agricultural policy. For programs open to many different sized communities, rural communities often deal with spending formulas or eligibility requirements that are particularly disadvantageous to them.

Source: Brookings analysis of the 2019 Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance

Note: Due to space constraints, this visualization excludes a small number of sub-agencies and offices that administer rural and tribal development programs. Lines drawn directly from department names account for programs administered by sub-agencies and offices that do not appear in the chart.

We tracked fiscal year 2019 funding flows for 93 of these programs, which exclusively target rural communities. They administered $2.58 billion in grants (just 0.2 percent of federal discretionary spending) versus $38 billion in loan authority.

FY2019 grant spending on rural-exclusive development programs, by agency

Source: Brookings analysis of USASpending data

Source: Brookings analysis of USASpending data

Note: USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture, DOT = Department of Transportation, HHS = Health and Human Services, ED = Department of Education, DOI = Department of the Interior, DOL = Department of Labor, ARC = Appalachian Research Commission, DOJ = Department of Justice, VA = Department of Veterans Affairs

Loan authority accounts for the vast majority of rural-exclusive development assistance

Source: Brookings analysis of USASpending data and USDA-RD FY2021 budget summary

The urgency of challenges facing rural communities makes a strong case for ambitious federal leadership to support economic and community development in the rural United States. To maximize the return on federal investment, our recommendations include:

1. Launch a domestic development corporation, modernizing technical capabilities and financing tools

A new corporation would competitively award large, flexible block grants that invest in local vision, accompanied by cutting-edge technical assistance, rigorous analysis and measurement of results, and support to strengthen local leadership and civic capacity. It would integrate and expand the breadth of domestic development financing tools, bringing strategy and improved impact to the set of narrowly defined and siloed tools that currently exist. The U.S. government has done this successfully for its international development investments by creating the Millennium Challenge Corporation and the International Development Finance Corporation; it should apply this experience to the development challenges facing rural communities in the U.S.

2. Create a national rural strategy and undertake associated reforms to improve coherence, regional integration, and transparency

As early as the 1970s, officials in the Carter administration noted that “the federal rural development effort consisted of programs, rather than policy.”1 A national rural strategy will strengthen coordination by providing clear policy direction to the agencies and stakeholders involved in rural development.

To ensure that strategy implementation responds to rural realities, we recommend elevating White House leadership by (1) establishing high-ranking positions responsible for rural and tribal development and (2) creating an office to facilitate interagency coordination and provide consistency and convening power across presidential administrations.

To be successful, a national rural strategy must embrace diverse rural perspectives while breaking down urban-rural divides by incentivizing regional approaches. An analysis of the impact, constraints, and successes of the seven regional commissions and authorities previously authorized would be a start. Special attention should be paid to addressing power dynamics that have historically excluded groups, and to promoting collaboration with a wide range of partners and intermediaries.

To complement the national strategy and ensure that rural areas have fair access to the federal assistance that can help advance their priorities, we suggest a federal rural audit—a close examination of eligibility, funding formulas, and spending criteria of community and economic development programs, identifying those that disadvantage or create barriers to entry for rural areas.

Coherent strategy requires a rigorous focus on transparency and results. To increase transparency, we recommend an easy-to-use web tool that tracks federal funding flows to rural people and places. We also recommend a congressional commitment to mandate and provide 5 percent of program funding for evaluation.

3. Appoint a bipartisan congressional commission to undertake a top-to-bottom review and build bipartisan momentum for improving the effectiveness of federal rural policy

The scale of operational and structural changes needed to make meaningful improvements will depend upon support and actions from both the legislative and executive branches, and from both political parties. To build and sustain momentum for the scale of change suggested in this analysis, we recommend a bipartisan, congressionally appointed commission undertake a top-to-bottom review of the effectiveness of federal assistance for rural community and economic development.

-

Footnotes

- Anne Effland, “Federal Rural Development Policy since 1972,” Rural Development Perspectives 9, no. 1 (1993): 8–14, https://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/IND20388541/PDF

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).