Congress is on the cusp of enacting a costly and ineffective new tax expenditure for workers with student debt as part of the broader coronavirus relief package. Rather than providing relief to distressed borrowers, the provision instead showers tax cuts on high-income workers with good jobs who are already paying off their loans, and introduces a perverse new incentive for higher-income families to borrow for college rather than pay out of pocket.

The provision is similar to the Employer Participation in Repayment Act, introduced by Senators Mark Warner (D-Va.) and John Thune (R-S.D.). It allows employers to pay up to $5,250 each year tax–free to employees with student loans. Employers would deduct that compensation from their taxes just as they do wages, but this would not be taxed as income to the employee. As a result, the new tax benefit is lucrative—but only to workers who are employed, have enough income to put them in a high tax bracket, and work for employers sophisticated enough to establish and provide the new benefit package. In short, the bill is remarkably well targeted at exactly those borrowers who need the least help.

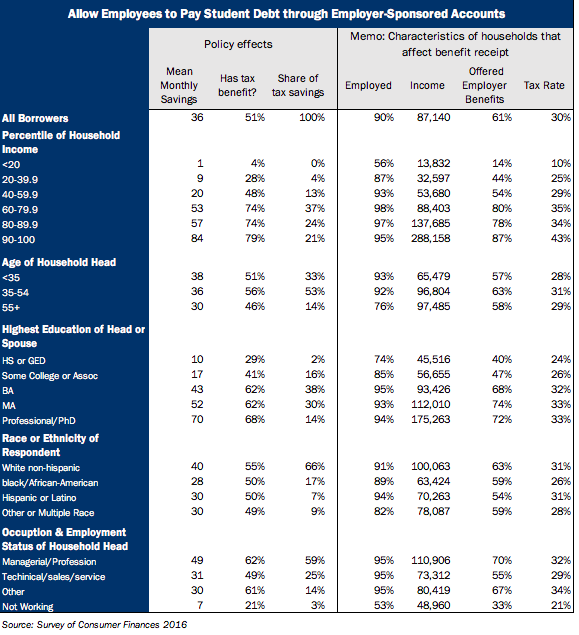

Using data from the Federal Reserve’s most recent Survey of Consumer Finances, I estimate that borrowers in the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution (those earning less than about $42,000) get about 5 percent of the tax benefit, saving about $5 per month, while the top 20 percent get about 46 percent of total benefits. By making student loan relief contingent on having a job and working for a generous employer, and the amount of relief dependent on the borrower’s tax bracket, Congress is pursuing a policy that is even more regressive than outright debt forgiveness.

Here are the details:

Under the terms of the bill, employers could establish educational assistance programs, which currently allow employers to provide tuition assistance for courses taken by an employee, to provide up to $5,250 per year, per worker in tax-free assistance for employees repaying student loans. Instead of being treated as wages, those payments would be excluded from income and payroll taxes (both the employee and employer portion).

Who does this help? First, only borrowers with jobs. According to the 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances, 10 percent of all households with student debt have no wage income. Second, even if you have a job, you need to work for an employer that offers generous benefits. In practice, surprisingly few workers are offered any employer benefits. Overall, 61 percent of households with student debt are even offered a 401(k) or a pension plan, and among those who are offered a plan, only two-thirds work at an employer that contributes or matches their contribution. That means that only four in every ten households with debt work for an employer willing to establish a matching 401(k) plan. The share who will establish and contribute to a student debt repayment plan is surely lower. For perspective, according to the National Compensation Survey, in 2007 (the last year of the relevant survey), only 15 percent of employers offered Educational Assistance Programs that were non-work related—the kind used, for instance, to reimburse employees for taking a course at a local postsecondary institution and the kind relevant for making student loan payments.

Not surprisingly, the decision of employers to offer benefits is contingent on the income and sophistication of their workforce. Households in the top 10 percent of the income distribution have a 70 percent chance their employer contributes to their 401(k). For middle-income households (those between 40-60th percentiles), only 34 percent work for an employer that contributes to their 401(k).

Finally, the value of a tax-exclusion of compensation from income and payroll taxes depends on whether the worker is in a high or low tax bracket. Using the SCF data and 2018 tax rates, I estimate that typical borrowers in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution face a total tax rate of about 10 percent, while those in the top 10 percent pay a 43 percent rate. In other words, each dollar of student loan payments funneled through these new accounts will save low-income borrowers an average of $0.10 and each high-income borrower $0.43.

Beyond simply being regressive, the bill targets loan relief to those who need it least.

Beyond simply being regressive, the bill targets loan relief to those who need it least. Low-income, unemployed borrowers who can’t make payments and default at high rates get no relief. But borrowers who are already making payments—at or above the $5,250 annual level—get the full benefit.

Of course, the bill is widely supported by business leaders—it offers them an opportunity to appear socially responsible with little cost to themselves by allowing taxpayers to be “paid back” for student loans with taxpayers’ money.

In addition to being ineffective at stemming the real problems in the student loan market, the bill threatens to do real damage to student lending and tax compliance.

First, providing generous tax breaks for workers with student loans could encourage more students to borrow, increasing indebtedness of future borrowers and the total costs of lending programs. In effect, this bill says that if you pay for college up front, out of your own pocket, you (or your parents) pay with money that has already been subject to income and payroll taxes. However, if you borrow that amount and repay the loan out of your employer assistance plan, then you pay for college with pre-tax dollars—a tuition discount that can be worth more than 40 percent if you’re in a high enough tax bracket.

Second, educational assistance programs weren’t designed to repay student loans. Employers don’t know which loans qualify, and there’s no reporting or compliance system to make sure tax-free employer payments to workers are used for student loans rather than other purposes. Those are problems that matter little with current educational assistance programs because employer payments typically go straight to pay tuition and fees. But student loans from both federal and private lenders can be used to finance not just tuition and fees, but a range of living expenses like rent, food, or transportation. The scope for abuse is significant.

There are many alternative ways to provide relief to student borrowers, from targeted approaches that help struggling, low-income borrowers to widespread debt forgiveness that also benefits highly-educated, well-off households—any of them are better. The best approach is to transition to a system of automatic income-driven repayment and a concurrent rehabilitation of existing loans and waiver of penalties for defaulted and delinquent borrowers who never had ready access to such programs.