The drastic measures to keep people at home as the COVID-19 pandemic spreads have decimated the small business sector. These vital businesses provide local amenities and experiences that enrich our lives and anchor our communities, and they’re a critical source of income and wealth generation for their owners. And a subset of small businesses—young businesses, which are zero to five years old—are the primary drivers of the nation’s net job creation and productivity growth.

Because small businesses have greater credit constraints and are more sensitive to weak consumer demand, they are often hit the hardest in economic downturns. The COVID-19 recession is uniquely damaging to them, especially those relying on foot traffic and social interaction.

As policymakers prepare relief measures to support small businesses, it’s helpful to look back at what happened to small businesses during the last major economic downtown, 2007 to 2009’s Great Recession. The COVID-19 recession will likely differ in severity and duration from the Great Recession, but it may nonetheless offer clues as to how small businesses experience economic contractions compared to larger businesses.

Small businesses had fewer workers but larger job losses during the Great Recession

The Small Business Administration’s definition of “small” varies by industry, but for the purposes of this analysis, we define small businesses as those with fewer than 250 employees, which is the highest standard to qualify in most industries.

During the Great Recession, these small businesses experienced disproportionate job loss compared to their share of total employment in the economy. Nationally, small businesses accounted for 45% of employment, but as the economy shed about 5 million jobs from 2008 to 2009, they accounted for 62% of the net job loss (Figure 1). Compared to the Great Recession, the early stages of the COVID-19 economic crisis suggest that job losses will fall even more disproportionately within the small business sector.

Micro businesses and young businesses are particularly vulnerable

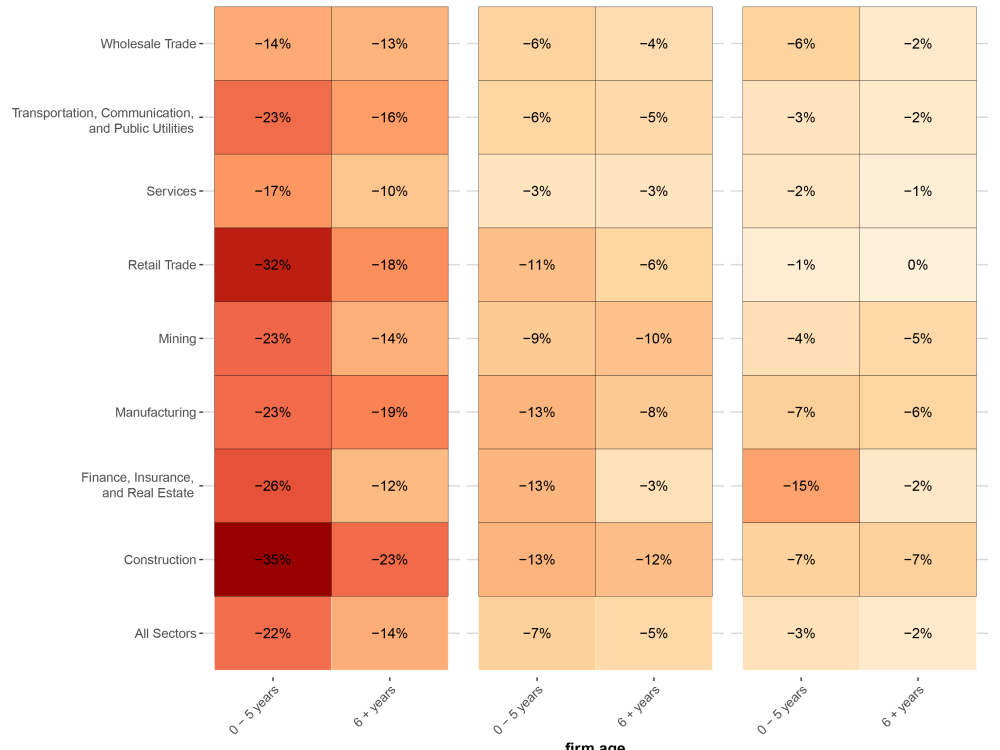

As policymakers develop responses to the severe economic contraction we’re facing, they should consider that job loss varies considerably by the age and size of the small business.

Generally, the older and larger a small business, the better it fared during the Great Recession. Micro businesses (fewer than 10 employees) and young businesses (zero to five years old) are most vulnerable across all sectors (Figure 2). The employment losses within young and micro businesses ranged from 15% in wholesale trade and services to nearly 35% in retail trade and construction, the latter of which reflects the role housing played in the Great Recession.

Restaurants and small retail outlets are likely to lead the losses during the early days of the coronavirus-fueled economic crisis. But eventually a major recession will hit every sector of the small business economy, as consumer and corporate demand decreases. This chain reaction begins first and most intensively with younger, smaller (and thus more vulnerable) businesses.

Geographic trends matter

Broader industrial and technological trends—and how those influence the dynamism of metro area economies—also played a role in how small businesses experienced the Great Recession. Small businesses are predominantly locally serving, meaning their viability depends on the health of the key export industries in their local economies.

Among the nation’s 100 large metropolitan areas, eight metro area economies actually managed to expand despite the Great Recession. This was mainly due to the energy boom, which kept demand for small business activity higher in regions in such as Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas (Map 1).

Most communities were not so lucky. In more than half of the nation’s 100 largest metro areas, small businesses accounted for at least 60% of net job losses. In 16 large metro areas, small businesses were responsible for more than 90% of net job loss. Metro areas that were hit hardest included Philadelphia, Fresno, Calif., Jacksonville, Fla., Bridgeport, Conn., Louisville, Ky., and St. Louis, Mo., among others.

Mitigate, then recover

Last week, we wrote about several small business relief strategies that local and state governments are pursuing, including emergency loan funds and tax relief. Still, not every small business is equipped to survive this downturn. But because small businesses contribute disproportionately to job loss during recessions, these policy responses are necessary. In our current crisis, these measures must occur immediately—which means that speed and simplicity are important considerations.

If speed and simplicity are required in the short-term, then scale is the operative word for the medium-term recovery. As of this posting, the Senate is on the verge of passing a relief package of at least $350 billion for small businesses. This federal package is critical, because locally led capital support will only take local economies so far.

In the long-term, policymakers and business development providers should remember that the Great Recession was distinctly damaging to small businesses. And that was at a time when shops and restaurants could still rely on social interaction and foot traffic for business—COVID-19 has stripped even that advantage away.

This crisis will demand a set of policy supports that are both broader and longer-term than those pursued in 2009. Otherwise, small businesses are certain to face a calamity.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What the Great Recession can tell us about the COVID-19 small business crisis

March 25, 2020