Last week the unthinkable happened for the nation’s climate and energy establishment: Donald Trump won the presidential election.

The result appears dire. Scholars, activists, and journalists have been wringing their hands at an anticipated “horror show of policy reversals and seediness,” as my Brookings colleague David Victor put it over at Yale Environment 360.

And the coming damage really could be grievous. As summarizes Vox’ Brad Plumer, Trump’s various statements this year have suggested that the president-elect: “[believes] global warming a Chinese hoax…wants to scrap all the major regulations that President Obama painstakingly put in place in reduce U.S. carbon dioxide emissions, including the Clean Power Plan…wants to get rid of the EPA entirely…wants to repeal all federal spending on clean energy…wants to pull the United States out of the Paris climate deal.” And with the GOP fully in control of Congress, much if not all of this seems doable.

In short, years of belated, painstaking work by the Obama administration and the world community to cobble together sound policies and structures for cleaning up the energy system and limiting global warming to acceptable levels appear threatened. As Plumer and his Vox colleague David Roberts put it, “Unified Republican control of the federal government over the next two years augurs a sea change in U.S. environmental policy like nothing since the late 1960s and ’70s, when America’s landmark environmental laws were first passed.”

At yet, without minimizing the gravity of the current moment, there are several solid (and not just wishful) reasons for maintaining some hope that progress can be maintained on the path of decarbonizing the economy and reducing the most devastating consequences of global warming. In this regard, many of the forces that have been most strongly shaping emissions outcomes in recent years remain beyond Trump’s reach and beyond the rules and stances of the U.S. federal government.

In keeping with that, here are three solid truths about where progress has been coming from thus far that point to genuine sources of consolation about further progress and priorities for the next stage:

States and cities will continue to lead.

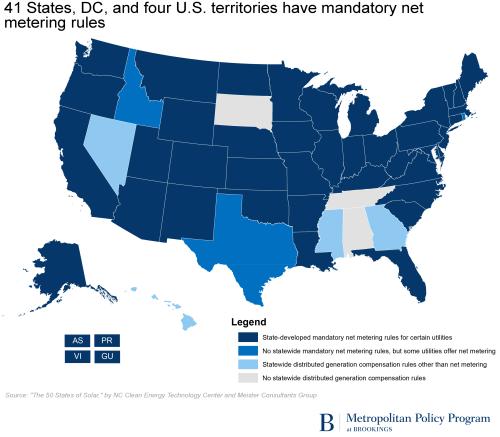

A first reassuring feature of the current situation is the fact that much of the legal power—and most of the creativity—to clean up the economy and reduce greenhouse gas emissions resides outside Washington, D.C. To be sure, nations are the most prominent units in international climate negotiations—and rules like this nation’s Clean Power Plan to compel power plants to slash emissions matter enormously. However, states and cities arguably matter just as much because they control so many of the most crucial policy levers that can control emissions. State commissions will continue to regulate investor-owned electric utilities, for example. State legislatures will continue to set and update renewable energy targets and portfolio standards. And cities will continue to manage land-use and transportation systems and enforce energy-efficient building codes. What is more, every sign to date suggests that globally consequential states like California and New York are going to double down on their respective climate policies. A forthcoming Metropolitan Policy Program paper will demonstrate that state-level decisions about fuel sourcing, economic structure, and other factors are delivering significant emissions reductions in dozens states. The bottom line: Progress can still be made even if Trump begins to dismantle national and global policies and processes.

Technology change and market forces will continue to drive gains.

Similarly, much of the nation’s recent progress on emissions reductions resulted from market dynamics, not policy, and will proceed without regard to Donald Trump’s preferences. For example, the largest major carbon advances in the United States over the last decade have resulted from market changes that have resulted from the onset, thanks to technology breakthroughs, of cheap natural gas and cheap renewables. The massive adoption of “hydraulic fracking” has unleashed a gale of cheap, lower-carbon natural gas that has been the main driver of a wholesale switch from coal to natural gas in fueling power plants. This will continue. At the same time, wind and solar power keep getting cheaper, and in some places they are becoming competitive with new fossil-fuel plants. Soon such renewables will become cost-competitive without federal supports. Beyond that, rapid declines in the costs of batteries for electric cars and storage for the grid will likely continue bolstered with innovations in energy efficiency and carbon management software. In short, though it might be slowed, the clean energy revolution is likely “unstoppable” thanks to entrenched tech and market trends, as Joe Romm of Climate Progress remarked last week. The issue then becomes defending, and speeding up, existing momentum and bringing online new technologies, such as conventional and new modular nuclear reactors (Trump seems to support nuclear expansion).

Private finance will continue to drive the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Finally, climate-oriented finance is gaining force. To be sure, direct federal investments, subsidies, and frameworks remain critical to support and accelerate favorable state-local and market-tech trends mentioned above. And to the extent those are reduced will be a problem. However, the prevailing consensus is that the bulk of the $10+ trillion that the International Energy Agency estimates will be needed to finance global decarbonization in the next 15 years will consist of private capital. And in fact, creative financing solutions have already been coming online to drive large-scale private and institutional capital flows into clean energy projects. Last year Microsoft founder Bill Gates launched the Breakthrough Energy Coalition, a consortia of billionaires focused on investing billions of private dollars to commercialize new technologies. Additionally, a series of “bottom-up,” public-private, and state-local climate finance initiatives have sprung up to move money into expanding low-carbon solutions. Multiple state “green” banks are leveraging limited public-sector funds with private-sector capital to provide low-cost and long-term loans to clean energy projects. Bond financing is being deployed as states and localities talk about how they can establish a new clean energy asset class that can easily be traded in capital markets to bring capital into the clean energy sector. And while global private investment has slowed somewhat this year, it remains significant, though it needs to grow. All told, private finance and bottom-up public-private partnerships to finance clean energy are proceeding and hold opportunities for growth.

There is no doubt that if the Trump administration accomplishes even a few of its campaign promises our nation’s—and the world’s—present regime for cleaning up the economy will be grievously damaged. Most notably, the loss of key federal policies and frameworks—such as federal rules on the burning of coal; budgets for federal clean energy R&D; or federal tax supports for clean technologies—could disrupt and slow even the most entrenched positive trends. And that is a huge problem given the need for speed in reducing emissions and forestalling dangerous effects of global climate change. According to Roberts, the fight has been lost to prevent dangerous climate change associated with temperature changes of more than 2 degrees above preindustrial above preindustrial levels, and the focus must turn to at least limiting temperature gains of significantly more than that.

Still, the fact remains that some progress can still be made, and must be made. States and localities will continue to retain broad powers. Technological and market trends will remain in force. And private finance will continue to invest in the market value of clean, cheap solutions. For those wanting to console themselves with productive engagement these are places to look.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Climate, energy, and Trump: Progress is still possible

November 15, 2016