First, the fracking boom strained state and local governments as unconventional oil and gas development generated population spikes, heavy truck traffic, and new service demands.

Now the fracking bust is straining government again. This time the pain involves idled drilling rigs, worker layoffs, and gaping budget holes.

Isn’t there a better way? There is, as we argue in a new paper released last week. States that are immersed in the hyperbolic boom and bust cycles of the fracking economy should move in two simple ways to smooth the ride out. They should tax extraction and then manage the revenues for the long term with permanent trust funds. Do that, and more “fracking patch” states will have a good shot at managing the cycles more strategically while at the same time working over the longer haul to “remake economic development,” as our colleague Amy Liu has said many places should.

The need for reform has become glaring this spring. Given the sheer scale and speed of the fracking-driven oil and gas boom and bust in recent years, the problem posed for governments—and state economies—by commodity price cycles has been thrown into stark clarity.

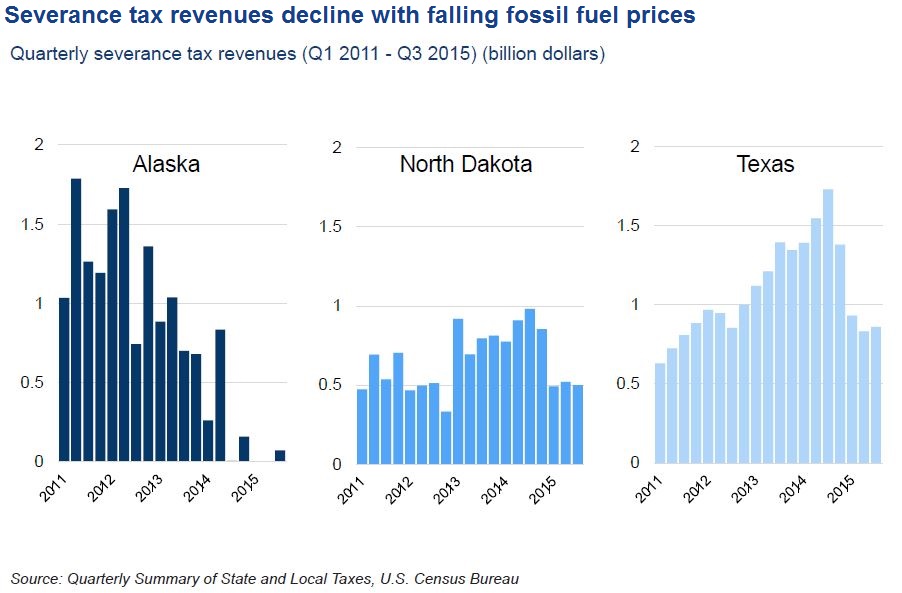

Most obviously the current oil and gas bust phase is wreaking havoc on the budgets of states as diverse as Alaska, Louisiana, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Pennsylvania. In these states, not only have sales and income taxes been hurt, but state reliance on imperfectly managed severance tax flows has led to volatile swings from fiscal plenty—and new programs—to yawning deficits and ugly budget cuts. Yet there may also be another troublesome dynamic at work, given that fracking cycles—rather than bankrolling investment in long-term economic diversification—may be recapitulating the so-called “resource curse,” by which natural resource dependency stunts the development of other less volatile, value-added sources of prosperity. Only some states, in this regard, seem to be making serious efforts to channel fracking gains into investments that will help the state transcend the down times with long-term gains.

Which is why we suggest states put in place, if they don’t have one, a reasonable severance tax on oil and gas extraction, and—once they have that—channel a portion of the revenue into a permanent trust fund designed to convert volatile near-term revenues from oil and gas extraction into a continuous, longer-term source of investment funds for building more sustainable, dynamic economies.

Getting the funds’ design right will be key. At the very minimum, suggests our research, permanent trust funds should be constitutionally protected and the corpus of the fund kept perpetual and inviolate——a strength of the Wyoming Mineral Trust Fund. At the same time, fund utility can be strengthened by specifying—as does the law governing the North Dakota Legacy Fund—a reasonable minimum contribution each year. It also needs stressing that that the management of the fund should be insulated from political decisions and day-to-day management entrusted to an entity with extensive experience in managing complex financial instruments, as is the case with the gargantuan Alaska Permanent Fund. Finally, as opposed to transferring fund investment earnings into general funds where it is difficult to track how specific general fund-dollars are spent, states should seize the opportunity to use fund earnings to invest in bold and transformative initiatives that build assets, create long-term prosperity, and enhance the quality of life for their residents. This is the strength of the Texas Permanent School Fund. More states should create such funds and dedicate the investments to purposes like education, economic diversification, or perhaps clean energy innovation.

The rationale is clear. The long history of the oil and gas industry has been one of booms and busts. Now the fracking revolution has intensified those cycles. Policymakers need to understand this dynamic and respond accordingly.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Funding economic change with fracking revenues

April 25, 2016