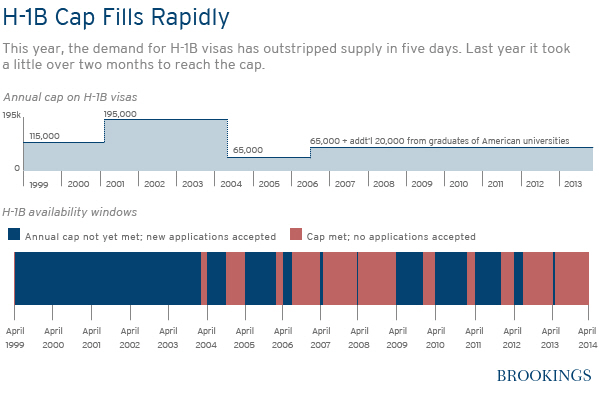

The annual H-1B visa scramble ended in just five days earlier this month. Due to high employer demand, 39,000 requests for H-1B workers were denied, and the 65,000 available visas were allocated using a lottery system. So it’s wait until next year for those out of luck.

However, change is afoot as the proposed comprehensive immigration reform bill from the U.S. Senate’s “Gang of Eight” could rewrite the rules of the H-1B race.

The Senate’s proposal attempts a balance between providing American businesses with more visas and protecting American workers.

On the one hand, the provisions almost double the visa cap from 65,000 to 110,000 (close to its level in the late 1990s), as proposed in the Immigration and Innovation Act of 2013 (I-squared), introduced in January. At the same time, it prioritizes the need for American-trained science and tech workers by targeting 25,000 visas for STEM master’s and doctoral graduates and boosting the number from 20,000 in the current law reserved for advanced degree-holders in any field.

On the other hand, it includes features from Sen. Grassley’s H-1B and L-1 Visa Reform Act of 2013, which raises wages for H-1B workers, requires employers to make an effort to hire American workers first by posting job openings publicly, and prevents abuse of the H-1B program by increasing fees for employers who are heavily dependent on H-1B workers. To further decrease reliance on the program, companies will be banned from employing more than 75 percent of their workers on an H-1B or L-1 visa in 2014, decreasing to 65 percent in 2015, and 50 percent in 2016.

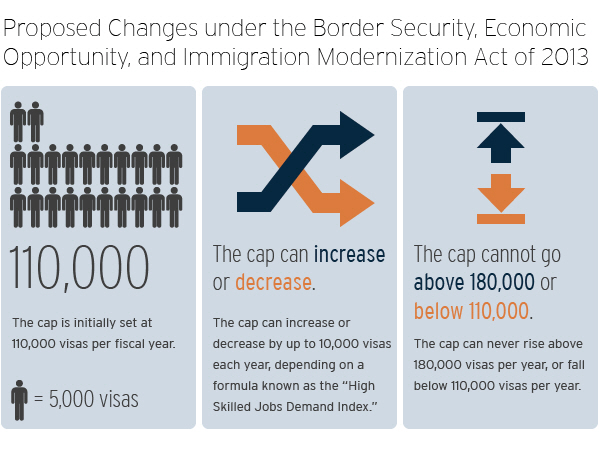

If passed, the bill would replace the static annual cap on H-1B visas with an automatic “H-1B escalator,” similar to what was proposed in the I-Squared Act in January. The new legislation raises or lowers the H-1B visa cap by up to 10,000 visas each year, so long as it never exceeds 180,000 or drops below 110,000. A “High Skilled Jobs Demand Index” would determine the actual amount by which the cap changes from one year to the next, based on changes in the demand for foreign labor and the availability of domestic workers. The Index as currently proposed would be calculated in terms of: (1) the number of H-1B petitions filed in the previous year in excess of the cap, as a share of that year’s cap, and (2) the percent change in the average number of unemployed individuals in “management, professional, and related occupations” (as defined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics).

How would the H-1B escalator apply to the coming year? As we wrote previously, employers sought 39,000 more H-1B visas than were made available under the base cap of 65,000 for FY 2014. According to the latest data available from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of unemployed individuals in “management, professional, and related occupations” decreased by 5.7 percent between 2011 and 2012. Using the proposed formula, the cap would increase by 31,463. Yet, because the cap cannot be adjusted by more than 10,000 visas each year, the total number of visas available this coming year would be 65,000 + 10,000 = 75,000.

Although the proposed index to set cap levels on H-1B visas is a balanced attempt at incorporating both demand for foreign skilled workers and the supply of the current American workforce, the formula should additionally allow for future adjustments, use unemployment data for more detailed occupational groups, and consider geographic variation.

Flexibility is Key. The occupations included in the High Skilled Jobs Demand Index should not be set in stone. The skills America needs may change in five, 10, or 20 years, so tying the visa system to fixed metrics is mistaken. Similar to our recommendations in “The Search for Skills,” the proposal to establish a new statistical agency (the Bureau of Immigration and Labor Market Research, to be housed within the Department of Homeland Security) to use data to designate labor shortages by occupation and location is well founded—as is its mandate to study and make recommendations on the effects of immigrants on the U.S. labor market. Such a body of experts would provide up-to-date analyses to inform future adjustments of immigrant admissions. However, under the new Senate proposal, the bureau is set up to devise its own methodology for changing the cap for the newly-created W visa for lower-skilled positions, but not for H-1B visas. If the High Skilled Jobs Demand Index remains the automatic method for annually adjusting the H-1B cap, the bureau should at least be able to make recommendations on changes to the formula based on occupational and geographic variation in the supply of and demand for high-skilled workers.

Precision Counts. The unemployment rates in the broad “management, professional, and related occupations” category differ significantly from those in more specific occupational categories for which H-1B demand is greatest. For instance, while the number of unemployed individuals seeking jobs in the “management, professional, and related occupations” category declined by 8.8 percent between 2010 and 2011, the decline in unemployment was significantly greater in the two subcategories with greatest H-1B demand. Unemployment in computer occupations declined by 16.9 percent, and among engineers by 23.5 percent (51.0 percent and 8.6 percent, respectively, of all H-1B petitions filed over this period by cap-subject employers were for workers in these occupations). To link supply and demand for labor more precisely, the formula should be based on specific occupational groups rather than the much broader category.

Place Matters. As we showed in our report, the demand for H-1B visas varies from place to place. For example, the Columbus, Ind. metropolitan area—which experienced economic growth throughout the recession—has the second-highest intensity of demand for H-1B workers in the nation, driven by engine manufacturer Cummins. In 2010, Columbus had an overall unemployment rate of 6.1 percent and a 3.0 percent rate among those with bachelor’s degrees and above, compared to the respective national rates of 10.8 percent and 5.0 percent in 2010. The annual determination of H-1B admissions levels should take into account metropolitan-level data on employer demand along with regional labor market indicators.

In sum, a new system that structures our future immigration flows to better meet the demand for high-skilled workers while at the same time protecting the American workforce is a delicate balancing act worth pursuing. As the bill moves forward in the legislative process, Congress should consider broadening the new statistical bureau’s purview to include H-1B admissions to ensure that the visa system can smartly respond to changing economic needs in the future.

Commentary

A Balancing Act for H-1B Visas

April 18, 2013