Editor’s Note: This blog post is part of The Primaries Project series, where veteran political journalists Jill Lawrence and Walter Shapiro, along with scholars in Governance Studies and the Campaign Finance Institute, examine the congressional primaries and ask what they reveal about the future of each political party and the future of American politics.

So far, the 2014 primary cycle casts doubts on the argument that blanket primaries will mitigate partisanship and polarization. Last week we published the report, “The 2014 Congressional Primaries: Who Ran and Why” that focused on the dynamics that have developed in the two major political parties through the 2014 primaries cycle. Although our report concentrated on Democrats and Republicans, we also collected data on third party candidates in California and Washington because of their nonpartisan blanket primary systems. This style of primary allows voters to cast ballots across political parties (or, in these cases, party preferences) with the top two vote-getters moving on to the November ballot.

Proponents of the open primary system argue it reduces political polarization and could end the gridlock that plagues our current politics. When California implemented their current version of the “top two” system just two years ago, blanket primary advocates cheered “California’s rebellion against party-centric politics” and argued the system would end polarization and ameliorate bitter partisanship. Six years ago when Washington reinstated a modified version of their “top two” primary, Secretary of State Sam Reed called the new electoral system “healthy,” declaring Washington voters the primary’s “big winners.”

Recently, a controversial op-ed by Sen. Charles Schumer (D-NY) reintroduced the blanket primary debate into political discourse, as Schumer called for the adoption of the blanket primary system nationwide. Singing a familiar refrain from years earlier, Schumer argued the “top two” system could begin to end “polarization in Congress” and partisanship. Of course, his argument was not without its critics (see responses from Five Thirty Eight, DailyKos, and the MonkeyCage).

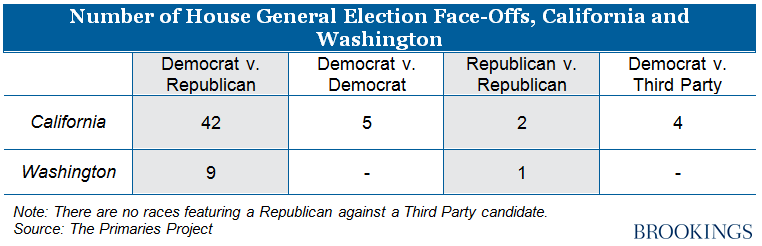

Looking at how these “top two” systems performed in 2014, however, raises significant questions regarding the reform advocates’ argument that a blanket system has a moderating effect on party politics. As the table below shows, over 80% of the primary outcomes maintain ‘Democrat versus Republican’ contests for the general election. However, of the exceptions, all five of the ‘Democrat versus Democrat’ races are in “solid Democrat” districts, according to The Cook Political Report, and all three ‘Republican versus Republican’ races are in “solid Republican” districts. Thus, it is worth asking, are the blanket primaries ending polarization or are they facilitating it?”

The reality is that we do not yet have substantial data on how the jungle primary affects polarization; however, California provides some insight into how that relationship can play out. It is critical to explore the possible scenarios.

Third Parties Still at a Disadvantage

A central argument in favor of the blanket primary system is that it gives third-party candidates more of a chance to make it to Congress. But out of 41 third party candidates in Washington and California, only four made it out of the “jungle.” Three of these candidates have “no party preference” and one candidate is affiliated with the “Peace and Freedom Party.” James Hinton (NPP-5) is running on a platform of “The Next New Deal.” Ronald Paul Kabat (NPP-20) is a perennial candidate, who uses his mascot “Wilbur Woof” to explain his positions. Steve Stokes (NPP-28) is calling for a “new paradigm” to replace major party leadership. And Adam Shbeita (PF-44) actually advanced to the general via a write-in candidacy, and campaigns on the issues of a $15 minimum wage and “free, high-quality public education.” All four candidates are facing popular Democratic incumbents this November and each of them has a steep, uphill climb to Congress. The reality is that in these races, the third party candidates who made it to the second round are weak candidates with little chance, if any, of winning.

Intra-party Clones

There are eight races in the blanket primary states that pit members of the same party against each other in November. That’s to be expected in congressional districts that are overwhelmingly of one party or the other. One goal of the primary system was to enhance choice in highly partisan districts in ways that benefit moderates. However, in some highly partisan districts—like many of those that pit two members of the same party against each other—that outcome is not guaranteed. In some liberal districts, two Democratic candidates hold very similar views on the issues, offering voters little substance on which to distinguish them. The same can be true for two Republicans facing off. In this scenario, the goals of the reform—decreased polarization—is not achieved.

Pulling Candidates to the Middle

If these new primaries are giving voters a choice between different factions within the same political party they are, for all practical purposes, increasing choice, moving what would have been a primary that excluded the loser into a general election that includes the second place finisher and fundamentally changing candidate strategies.

A case in point is California’s 4th congressional district where West Point graduate and Army Veteran Art Moore will face off against the incumbent Congressman, Tom McClintock a tea party supporter. Moore doesn’t look too much like your typical far right Republican. In fact he supports a woman’s right to choose and he supports gay marriage. McClintock beat him in the blanket primary by a hefty margin. In a traditional primary that would have been the end of the race and McClintock would have gone on to hold his central and northern California district. But in the new blanket primary Moore is on the November ballot where he’s hoping that between moderate Republicans and Democrats he can actually unseat the incumbent. McClintock clearly sees the dangers in this new primary and could be heard arguing on Fox News a few months ago about how the new system allowed candidates to “manipulate” the field. The fear for the conservative Republican is his opponents appeal to moderates and to Democrats—an outcome more in line with the goals of the reform.

While Oregon is set to vote on a “top two” ballot measure this November, we find little evidence so far that California and Washington have delivered on the blanket reform’s promises. Next month, we will have a few more data points on whether this cycle’s blanket primaries have stunted partisanship and polarization in the general election or whether they have advanced them. The system is so new that if any of the third party candidates or same party challengers come close in November (or even win) the strategic calculations of future challengers could shift significantly.

(For any methodological questions, please consult the Appendix of the original report.)

Commentary

The Primaries Project: Blanket Primaries Have Yet to Deliver

October 10, 2014