On the morning of Jan. 6, 2021, Steve Bannon encouraged the audience of his podcast not to waver in their faith. “We’re coming in right over target,” President Donald Trump’s former chief strategist intoned. “This is the point of attack we always wanted…today is the day we can affirm the massive landslide on November 3.”

In the aftermath of the ensuing attack on the Capitol, Bannon’s podcast stands out for its prescient blend of violent rhetoric and blatant disinformation. In the run-up to Jan. 6, Bannon and his podcast guests extensively promoted the false belief that Trump had rightfully and overwhelmingly won the November election, only to have it stolen from him by fraud. In doing so, Bannon was one of several prominent podcast hosts to champion the misleading electoral narratives known collectively as the “Big Lie.” While digital platforms like Facebook and Twitter have received significant scrutiny for their role in permitting the spread of those narratives, far less attention has been paid to podcasting. By virtue of both its intimacy and its scale, podcasting can serve as a powerful vector for misinformation, yet there has been comparatively little analysis to date of the role the podcasting ecosystem played in the lead up to the Jan. 6 attack.

To better understand that role, we compiled a dataset of the most popular political podcast series in the United States in November 2020. More specifically, we examined the “Top 100” list for that month from Apple Podcasts, the most widely used podcast app in the United States at the time, and then downloaded episodes for 20 of the 23 series in the Top 100 that we identified as primarily providing political commentary. We found that:

- Between Aug. 20, 2020, when the then-candidate Joe Biden accepted the Democratic nomination, and the storming of the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, over 25% of all episodes in our dataset (393 of 1,490) endorsed misleading electoral narratives

- The rate at which popular podcasts endorsed misleading narratives rose dramatically after the election, with more than 50% of all episodes (344 of 666) between November 3 and January 6 endorsing unsubstantiated allegations of voter fraud or related claims

- Popular podcasters on the right, who were largely responsible for the proliferation of electoral misinformation during this period, are more ideologically homogenous in their partisan leanings than popular podcasters on the left

- Episodes that endorsed false or misleading electoral narratives had broad cross-platform reach, with total audiences on Twitter and YouTube in the tens of millions

These findings suggest that the most popular political podcasts in the United States played a critical and underappreciated role in spreading false electoral narratives prior to the Jan. 6 attack. At a time when just one-third of all Republicans say they will trust the outcome of the 2024 presidential election results regardless of who wins, the findings underscore the need for further research on the political podcasting space. Without a better understanding of how the Big Lie spread so widely in the weeks and months after last November’s election, similarly false narratives are likely to plague future elections as well, with dire consequences for American democracy.

Shades of the Big Lie

The unsubstantiated claim that former President Trump won the 2020 presidential election represents a major and enduring threat to the integrity of U.S. democracy. By insisting without evidence that the election was plagued by fraud and that Trump was the rightful victor, supporters of the former president have cast doubt not only on the legitimacy of the current occupant of the White House but also the democratic process writ large. With 36% of Americans doubting that Biden legitimately won the last election, the stage has been set for the future elections to be delegitimized before they even take place. As the legal scholar Richard L. Hasen has argued, “the democratic emergency is already here.”

A key question is how exactly that emergency arose and what enabled the Big Lie to spread so widely. Although journalists, researchers, and academics have largely focused on the critical role played by digital platforms like Facebook and Twitter, there has been comparatively little focus on podcasts, despite the growing popularity of the medium. The reach and scale of the podcasting ecosystem has exploded in recent years, with Spotify and Apple alone now boasting more than 25 million monthly podcast listeners each in the United States. Major political commentators have taken note, with prominent figures from both the Obama and Trump administrations launching massively successful podcasts. Yet conservative commentators in particular have flocked toward the medium. Just as Rush Limbaugh, Glenn Beck, and Sean Hannity exploited the infrastructure of talk radio from the late 1980s through the early 2000s to establish themselves as major players in conservative politics, they and a newer generation of hosts are using podcasts to build large and influential audiences in a far more decentralized medium.

In light of the wide reach podcasting now enjoys, understanding whether and how political podcasts contributed to the spread of the Big Lie is vital. To do this, we compiled a dataset of popular political podcast episodes from series featured in Apple’s “Top 100” podcasts in November 2020.[1] We filtered this dataset for episodes released between the first major party convention on Aug. 20, 2020, and the storming of the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. We then searched transcripts of those episodes for a list of keywords associated with different claims of electoral fraud, including both generic terms like “stolen election” and “rigged election” as well as references to specific conspiracy theories, such as “sharpies.” Finally, we reviewed each keyword match manually to ensure that a podcast host or guest was endorsing or promoting an unsubstantiated allegation or false electoral narrative, rather than merely describing or reporting on one.[2] Our methodology means that it is unlikely our data includes false positives (i.e., instances where we coded a false or misleading claim when we should not have), but it may include false negatives (i.e., there may be instances where we did not code a false or misleading claim when we should have, since a podcast host or guest may have made a false claim that did not trigger a keyword match). Furthermore, due to data restrictions, some series had episodes that we were not able to download. This was an issue in particular with Rudy Giuliani’s Common Sense podcast, for which we were only able to access two episodes that aired after the election. Since Giuliani repeatedly endorsed false claims in other fora, it is likely that our data for his podcast series represents a significant undercount.

All told, we found that misleading electoral narratives meant to cast doubt on the legitimacy of the election were endorsed by a host or guest in 14 of 20 series and 393 of 1,490 episodes.[3] See the appendix below for a full table of episodes and counts.

The Big Lie in the mainstream

Based on our data, several key trends about how false and misleading electoral narratives spread within mainstream political podcasting stand out.

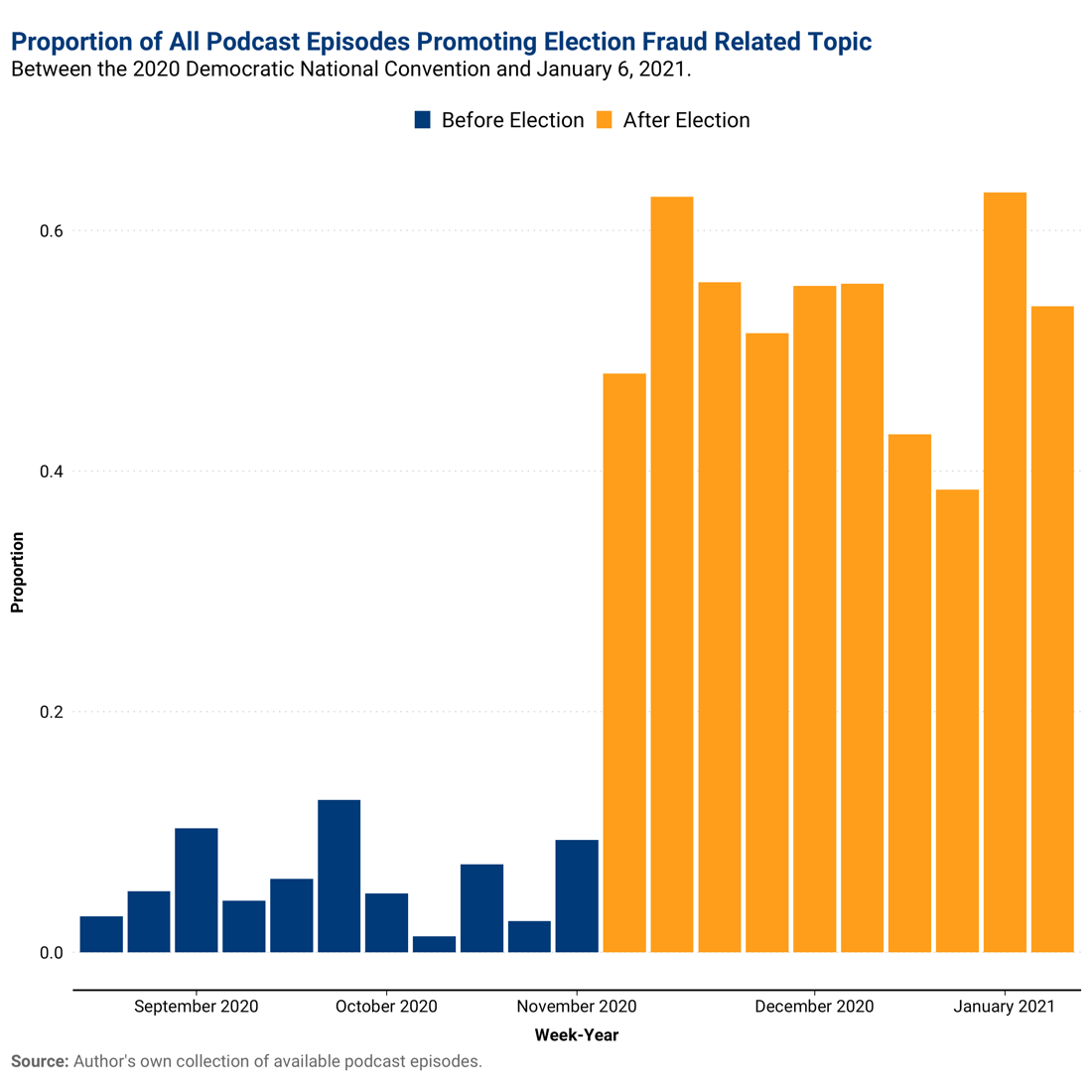

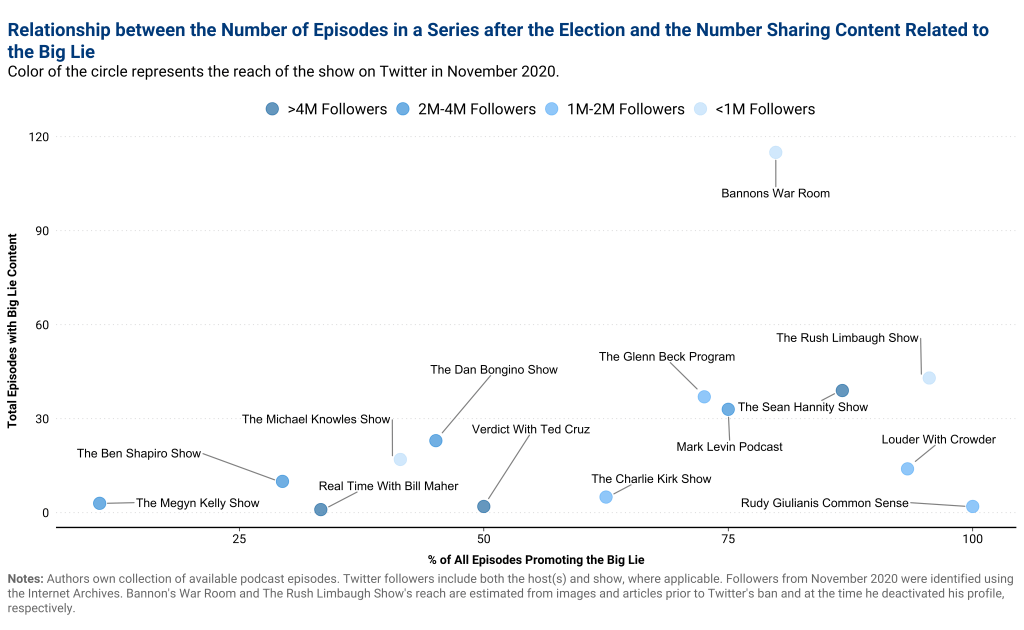

First, as Figure 1 reveals, there was a massive and sustained post-election increase in episodes that endorsed unsubstantiated allegations of voter fraud and related narratives. Although Steve Bannon and others had consistently raised concerns about electoral integrity prior to Nov. 3, the percentage of all episodes that actively endorsed or promoted them nonetheless remained relatively low in the pre-election period. By contrast, after Nov. 3 the number spiked dramatically, with just over 50% of episodes in our sample of popular U.S. political podcasts endorsing false or misleading claims. Significantly, as Figure 2 illustrates, the reason for the high rate is not that each popular podcast series was endorsing false election claims in one out of every two episodes, but that the podcasts that endorsed false narratives most frequently—such as The Sean Hannity Show, The Rush Limbaugh Show, and Steve Bannon’s War Room—were also those that produced the largest total number of post-election episodes. The trend is in keeping with Bannon’s stated Trump-era media strategy of “flooding the zone” with inflammatory information, real or fabricated.

Figure 1

Figure 2

The post-election increase in misleading electoral claims proved remarkably durable. The Electoral College has a “safe harbor” deadline by which time states are required to resolve all election-related disputes, which last year was Dec. 8. In theory, concerns about electoral fraud should have declined dramatically after that deadline. Yet as Figure 1 shows, the rate at which popular political podcast episodes endorsed misleading narratives declined only modestly after the “safe harbor” deadline passed, before rising again. In the week prior to the Capitol assault, 60% of popular U.S. political podcasts endorsed election fraud narratives. By that point claims of widespread voter fraud had failed to be substantiated.

The role of podcasts in spreading election fraud narratives was especially important after Nov. 3, as influential outlets within the conservative media ecosystem declined to back Trump’s claims that the election had been stolen. Whereas some hosts at Fox News cut away from Trump administration officials’ briefings about election fraud and outlets owned by media mogul Rupert Murdoch urged Trump to accept defeat gracefully, right-wing podcasts provided an unfettered venue to spread the lie that the election had been stolen.

With few in the mainstream media willing to entertain Trump’s claims of election fraud, podcast hosts expended considerable effort attempting to make them appear credible. Several podcasters pointed to the legal ramifications of signing false affidavits or highlighted the credentials of Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani (who “took down the mafia in New York City”) and Sidney Powell (who “worked for Michael Flynn”) to signal their credibility. Other podcasters blindly parroted even the most farfetched narratives, including those that claimed Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez had played a role in rigging the election, alleged that rogue USB cards had added votes to the election tally in Pennsylvania, or blamed the distribution of sharpies for Biden’s win in Arizona.

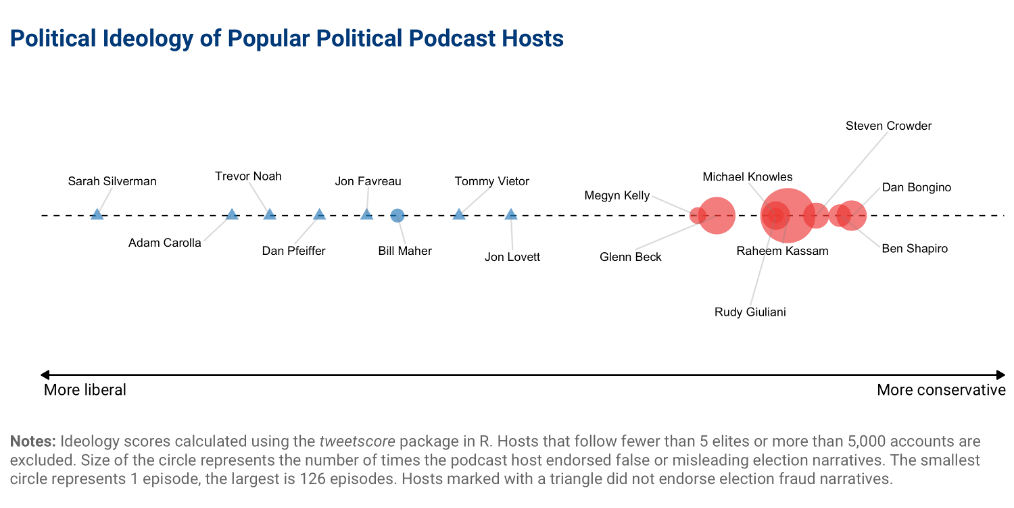

As Figure 3 shows, the podcasts that endorsed false and misleading electoral claims were not just more conservative, but also tended to be more ideologically homogeneous, at least as calculated by the accounts they follow on Twitter.[4] Whereas popular pundits on the left stretch across the ideological spectrum—note the broad gap between Jon Lovett of “Pod Save America” and the comedian Sarah Silverman—those on the right are much more tightly clustered. What this suggests is that the most popular liberal hosts represent a wider set of ideological views than those on the right.

Figure 3

What’s also striking about Figure 3 is that many of the hosts draw from a newer cohort of media figures.[5] Alongside familiar faces like Megyn Kelly and Glenn Beck, our dataset also included a newer generation of pundits, native to the digital age. Ben Shapiro, Dan Bongino, and Steven Crowder, for example, are among the most popular hosts in our sample, and have remained on Apple’s Top 100 list over the past year—a signal of their growing reach and appeal.

While it is difficult to determine the exact reach of podcasts, this new generation of hosts are using the medium to build sizeable audiences. Apple doesn’t disclose download numbers for its “Top 100” podcasts, but Ben Shapiro’s podcast claims to see 15 million downloads per month, while The Verdict with Ted Cruz reportedly had at least 20 million downloads in 2020. Yet because podcasts are often cross-posted on other media, podcast downloads alone do not capture their full reach. For series cross-posted on YouTube, episodes that promoted false election narratives collectively received 14 million views and over 700,000 likes. Given that this data is unavailable for all episodes, and many people do not listen to podcasts on YouTube, this level of engagement represents the lowest possible floor in terms of listener reach. Some podcasts in the sample are also rebroadcast over terrestrial radio, adding further complication to determining reach. Likewise, the Twitter followings of each podcast series and their hosts was also substantial. The podcasters who shared false election narratives in our dataset combined for over 40 million Twitter followers in November 2020, with a median Twitter follower count of over 2 million.

Conclusion

Two weeks after the election, Chris Christie, the former New Jersey governor and Trump adviser, appeared as a guest on Megyn Kelly’s podcast. “You can’t stand up there and say, ‘there’s been fraud, the election’s been stolen, and I would have won easily,’” he explained, “unless you produce evidence.” In the world of right-wing podcasts, Christie’s admonition fell on deaf ears.

In the aftermath of the election, mainstream political podcasts repeatedly and consistently endorsed unsubstantiated voter fraud allegations and other false election narratives, even after the safe harbor deadline had passed. In the days before the Capitol riots, for example, anyone listening to the Mark Levin podcast heard claims that in Georgia “they have well over a hundred thousand examples of people who voted that were dead, who were too young to vote,” while the Trump adviser Peter Navarro insisted to Sean Hannity that there was an “absolute flood of illegal ballots into Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania, in Wisconsin, in amounts more than enough to tip the balance to Joe Biden. It was an illegal stolen election.”

To their credit, several platforms have taken steps to curb the reach of podcasts spreading the Big Lie and other false electoral information. Shortly after the safe harbor deadline, for example, YouTube launched an effort to remove content alleging “widespread fraud or errors changed the outcome of a historical U.S. Presidential election.” The policy led the platform to take down Steve Bannon’s channel altogether on Jan. 8, after an episode in which Rudy Giuliani claimed the election had been stolen. Nonetheless, the podcasting space has still largely escaped scrutiny for its role in spreading false election narratives, much less the kind of robust public debate over how best to moderate online content that have pushed social media platforms toward greater transparency and more mature practices. In its absence, additional research and debate regarding how best to curb misinformation in podcasts is urgently needed if we are to avoid another election cycle marred by unsubstantiated claims of election fraud.

Valerie Wirtschafter is a senior data analyst in the Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technology Initiative at the Brookings Institution. She received her Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of California, Los Angeles.

Chris Meserole is a fellow in Foreign Policy at the Brookings Institution and director of research for the Brookings Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technology Initiative.

Appendix Table

| Show name | Total episodes | Episodes endorsing election fraud | Proportion |

| The Rush Limbaugh Show | 96 | 50 | 0.52 |

| The Sean Hannity Show | 97 | 48 | 0.49 |

| Bannon’s War Room | 263 | 127 | 0.48 |

| Louder with Crowder | 40 | 16 | 0.40 |

| The Glenn Beck Program | 119 | 47 | 0.39 |

| Mark Levin Podcast | 97 | 33 | 0.34 |

| The Michael Knowles Show | 84 | 21 | 0.25 |

| The Dan Bongino Show | 110 | 26 | 0.24 |

| The Ben Shapiro Show | 84 | 10 | 0.12 |

| Rudy Giuliani’s Common Sense | 17 | 2 | 0.12 |

| Verdict with Ted Cruz | 17 | 2 | 0.12 |

| The Charlie Kirk Show | 71 | 7 | 0.10 |

| Real Time with Bill Maher | 12 | 1 | 0.08 |

| The Megyn Kelly Show | 47 | 3 | 0.06 |

| Adam Carolla Show | 97 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Lovett or Leave It | 29 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Pod Save America | 48 | 0 | 0.00 |

| The Candace Owens Show | 9 | 0 | 0.00 |

| The Daily Show with Trevor Noah | Ears Edition | 137 | 0 | 0.00 |

| The Sarah Silverman Podcast | 16 | 0 | 0.00 |

[1] We identified popular political podcasts at the time by selecting the punditry-based podcasts from Apple’s Top 100 list in mid-November 2020. Political podcasts series include those that either (1) mention politics, policy, or current events in their show description; or (2) released a recent episode that covered political topics. The shows in our sample include: (1) The Adam Carolla Show; (2) Louder with Crowder; (3) Lovett or Leave It; (4) Pod Save America; (5) The Ben Shapiro Show; (6) The Candace Owens Show; (7) The Charlie Kirk Show; (8) The Dan Bongino Show; (9) The Megyn Kelly Show; (10) The Michael Knowles Show; (11) Mark Levin Podcast; (12) The Glenn Beck Program; (13) The Sean Hannity Show; (14) Verdict with Ted Cruz; (15) Bannon’s War Room; (16) Rudy Giuliani’s Common Sense; (17) The Rush Limbaugh Show; (18) Real Time with Bill Maher; (19) The Daily Show With Trevor Noah – Ears Edition; and (20) The Sarah Silverman Podcast. Due to data limitations, we are unable to compile episodes for three popular series during this period: (1) the Rachel Maddow Show; (2) the Lincoln Project; and (3) Tim Pool Daily. Bannon’s War Room RSS feed does not go back to the fall of 2020, so these episodes are downloaded directly from his website. Most of Rudy Giuliani’s Common Sense podcast episodes are no longer available online, so our inferences for this series are extremely restricted.

[2]The dictionary of terms used in our search draws on popular lies, phrases or statistics commonly referenced during this period. Election fraud related topics include: election fraud, software glitch, counting error, fraudulent biden elector, forensic electronic audit, forensic audit, voter integrity project, illegitimate president, election integrity, stop the steal, stop the steel, thrown out ballots, ditch along a wisconsin road, illegally flipped, missing usb cards, ballot stuffing, election irregularities, hugo chavez, indra, 800000 votes in pennsylvania, out of state license plates, 430 in the morning, venezuelan software, dominion company, 68 error rate, election hoax, surprise ballot dump, dominion systems, smartmatic, 450000 ballots, 3062 instances of voter fraud, stolen election, sharpies, dominion voting, arizona audit, voting machines, duplicate ballots, cyber ninjas, and rigged election. All episodes that referenced one of the terms in our dictionary were manually reviewed by two separate coders. Any discrepancies were resolved by a third coder.

[3] This dataset represents a subset of a larger corpus of more than 30,000 podcast episodes from 69 prominent political podcasters that we have transcribed using speech-to-text methods or, where applicable, the YouTube API to collect video captions.

[4] This strategy for identifying political ideology builds off Pablo Barberá’s 2015 Political Analysis paper, which details a method to calculate the political ideology of Twitter users based on decisions about who they choose to follow. The underlying assumption is that Twitter users will often follow accounts that reflect their political interest, which can then be used to develop a measure of their political ideology. In order to ensure the precision of ideology estimates, we exclude users who follow fewer than five “elites” or more than 5,000 accounts. More details on the methodology and implementation can be found here.

[5] Sean Hannity follows just six people on Twitter and Candace Owens follows 30 people on Twitter. As a result, we are unable to calculate their “ideological score.” Charlie Kirk and Ted Cruz follow over 5,000 people on Twitter. As a result, relying on their following network may produce skewed results due to following practices that may not be reflective of interest in the account.

Facebook and Google provide financial support to the Brookings Institution, a nonprofit organization devoted to rigorous, independent, in-depth public policy research.

Commentary

Prominent political podcasters played key role in spreading the ‘Big Lie’

January 4, 2022