This report is part of the Series on Regulatory Process and Perspective and was produced by the Brookings Center on Regulation and Markets.

Amidst the furor over President Donald Trump’s instantly infamous immigration actions, it has become difficult to remember that this is supposed to be his Administration’s honeymoon period. But there are issues on which he and the GOP Congress should be hand-in-glove, with regulatory reform and deregulation at the top of that list, and you’d think the honeymoon would go on for those. While there are indeed plenty of areas where Republicans are likely to be unified by regulatory issues, though, there are others in which it is easy to imagine Congress and the Executive Branch at odds with each other. This post briefly takes stock of where things stand now, and considers three interbranch dynamics that could emerge for regulatory politics: limited cooperation, institutional conflict, and an unusual alliance of Congress and the White House against the administrative state.

Regulatory Reform Progress to Date in Congress and the White House

As members of the Congressional GOP consider what they can accomplish with a fellow Republican in the White House, one of their priorities is to “clear out the regulatory underbrush so we can get economic growth going.” Early targets include a number of substantive regulatory policies from the Obama administration that Congress hopes to quickly reverse, including using the Congressional Review Act to repeal EPA and Interior Department rules (with new targets every day); a bill to repeal newly promulgated school nutrition standards; and several measures aimed at partially deconstructing or entirely repealing the Affordable Care Act, which contains many regulatory provisions in addition to its more famous and controversial pieces.

The House has also shown a strong interest in restructuring the processes that create and evaluate regulation, with the goal in many cases to give Congress more direct control over them. Noteworthy in this vein are the SEC Regulatory Accountability Act, which would subject the Securities and Exchange Commission to more stringent cost-benefit requirements; the Separation of Powers Restoration Act (SOPRA), which would instruct courts not to defer to executive agencies’ statutory interpretations; the Regulations from the Executive in Need of Scrutiny Act (REINS), which would force all new major rules to get affirmative Congressional approval before they could become law; and the Regulatory Accountability Act (RAA), which would create additional procedural requirements for major rulemakings, including requiring agencies to show that their preferred approach is consistent with the best evidence and minimizes costs as much as possible. All of these ambitious reforms have already been passed by the House (SOPRA as a title in RAA).

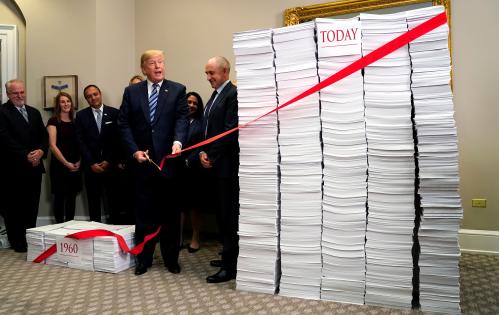

The Trump Administration has also prioritized the need to relieve regulatory burdens on businesses. President Trump recently told a group of U.S. business leaders he believed his Administration could cut regulations by “75 percent” or more. His administration’s regulatory freeze, while consistent with the practice of the past two administrations, brings all unpublished rules to a temporary but possibly indeterminate halt. The freeze has delayed the effective date of 30 regulations at the EPA alone. Trump’s FCC Chairman, Ajit Pai, is expected to target net neutrality rules for reversal. Any use of the Congressional Review Act will require President Trump’s signature—something that the President seems eager to lend. It is clear that Trump’s appointees will continue to target many of the Obama administration’s hard-fought victories in the regulatory arena for reversal, including signature climate change efforts such as the Clean Power Plan.

When it comes to process reform, however, the new Administration’s commitments are somewhat less clear. Trump’s Executive Order of January 30 mandates that for every new regulation promulgated, two must be removed from the books, and also effectively creates a regulatory budgeting principle, although many of the most important details are left to be worked out later by the White House’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB). If successfully implemented and if exceptions are kept minimal (both big ifs), this would be a major process reform—one that would probably greatly empower the director of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), which is the office within the OMB charged with overseeing the Executive Branch’s regulatory functions.

But how will Trump react to Congressional reforms specifically aimed at limiting executive discretion?

But how will Trump react to Congressional reforms specifically aimed at limiting executive discretion? Then-primary-candidate Trump promised to both advocate for and sign REINS, but it is easy to imagine that actually gaining the “reins” controlling the country’s rulemaking agencies might make Trump think differently about whether Congress should have the final say on their important output. Likewise with SOPRA, which would (or at least aspires to) tell courts not to defer to Executive Branch agencies’ interpretations. Will Trump really be happy to sign that into law, even when it is his agencies having their interpretive discretion curtailed? Of course, process reform need not be a zero-sum struggle for power between the branches, but, on matters like these, we would expect interbranch relations to be at their most oppositional.

Looking Ahead: Three Reg Reform Scenarios for the 115th Congress

With these basics in mind, let us consider three of the most likely scenarios for regulatory reform in the current Congress.

- Deregulation Kumbaya: Given the obvious benefits of a cooperative working relationship for both the Congressional GOP and the Trump administration, and given their common ground on regulatory issues, perhaps they will simply find ways to avoid the most difficult interbranch issues and come together on a significant deregulatory agenda. To the extent both Trump and Congressional Republicans are motivated first and foremost by revving up the economy, this cooperative scenario seems plausible. In this case, process reforms will find success if, and only if, they serve to relieve burdens on regulated industries; where they advance deeper and more controversial constitutional reordering, they will fall by the wayside as needlessly divisive. Given the transcendent importance of partisanship in our system in recent years, this scenario should perhaps be seen as par for the course. Some version of the 2-for-1 Executive Order, perhaps solidified or amplified by Congressional action, could fit this template.

- Ambition Counteracting Ambition: But Trump is famously not just like other Republicans, and it remains to be seen whether he can ultimately play nicely with his copartisans down Pennsylvania Avenue for a whole term—indeed, tensions are already mounting. Perhaps Congress will come to see prioritizing its own institutional interests as a major priority during his presidency. Certainly, that could become a bipartisan cause among legislators if some scandal inspires a large majority of the public to make combatting presidential abuse of power a top priority. In that case, the famous reforms of 1973-1974 might look like the model, with a resurgent Congress imposing its will on a resistant Executive Branch. Or, of course, it’s possible the president might be sufficiently popular to resist and frustrate such reform attempts. Either way, regulatory reform might well become one of the many areas in which the first and second branches exchange fire as they vie for control of federal policymaking.

- Trump-as-Outsider Plays Congressional Enabler: Much of political science can be boiled down to the maxim: “Where you stand depends on where you sit.” A politician’s stances are often functions of the opportunities his office makes available to him. Trump’s position as head of the Executive Branch would then be expected to define many of his Administration’s views on executive power. But what if, as in so many other ways, Trump is just different, such that he confounds these normal expectations? What if his chip-on-the-shoulder outsider self-conception means that, even as president, he will continue to see “the government” as a fundamentally alien, elitist body bent on frustrating his terrific desires? If “the deep state” (a term recently gaining currency) actively resists his leadership, this comes to seem like a real possibility. In that case, Trump might be enticed to side with congressional Republicans against the traditional interests of the Executive Branch. In that case, Congressional Republicans thinking big about limiting the administrative state and enhancing their branch’s constitutional position may have a golden opportunity in the coming years.

Each of these scenarios represents some group’s wishful thinking: business, Congressional institutionalists, and administrative state haters, respectively. One of these groups may soon see its interests served through regulatory reform—or, of course, there is always a chance that a snafu-ridden government will fail to make any systematic changes at all.