This report is part of the Series on Regulatory Process and Perspective and was produced by the Brookings Center on Regulation and Markets.

Newly elected presidents often try to eliminate policies of the prior administration, and President Trump’s campaign was devoted to reversing those of the Obama presidency. He called Obama’s foreign policy a “threat to our country” and “the worst thing to ever happen to Israel”. He tweeted graphs of Obama’s supposed economic failures. Calling the Affordable Care Act (ACA) a “catastrophe” in a Pennsylvania campaign speech, he vowed to “immediately repeal and replace” it. Throughout his campaign, Trump vowed to reverse these and many other signature Obama-era policies, notably several “job-killing” regulations related to the environment, labor, finance, and consumer protection.

Methods of Policy Reversal

Trump is certainly not the first president promising to repeal the policies of his predecessor upon assuming office. Incoming presidents, particularly those from the opposing party of the previous administration, often try to clear out old policies to make room for their own. They can do so in several ways.

First, presidents can work with Congress to pass legislation. New laws must be made to completely nullify old ones, such as the ACA or the Dodd-Frank Act. Lawmaking, however, is exceedingly difficult in an era of increasing divided government, legislative gridlock, and party polarization. Even when Republicans controlled the House, Senate, and presidency in 2017, their attempts at repealing the ACA failed. Congress can likewise rescind regulations within 60 legislative days of its promulgation through joint resolution, under the 1996 Congressional Review Act (CRA). Given that the president must still sign such a resolution for it to be effective, this is not so different (or so much easier) than simply passing new legislation. With the exception of the 14 regulations the 115th Congress repealed, mostly in early 2017, this law has been rarely invoked. There are only a limited number of rules it can target given the narrow time frame requirement and the fact that outgoing administrations can fast-track rules to avoid this fate.

Second, unilateral directives (i.e., written instructions given to agencies on how to implement the law) provide presidents a more direct way of reversing policy. They do not require congressional approval and can sidestep the collective action problems inherent in lawmaking. Making good on his promise to “eliminate every unconstitutional executive order” issued by Obama during his first year in office, Trump revoked 11 of Obama’s orders related to climate change, labor protections, and law enforcement. Presidents have long used unilateral directives to reverse the policies of their predecessors from the opposite party. This strategy, however, is not without its limitations. Threats of legislative or judicial retaliation, public backlash, and substantial transaction costs within the executive branch serve as deterrents to unilateralism. Furthermore, unilateral actions are less durable than other means of policymaking, given that subsequent presidents can easily rescind them with the stroke of a pen.

Lastly, presidents can reverse policies through the regulatory process. Shortly following his inauguration, Trump famously mandated that two regulations be repealed for every new one promulgated in his “2-for-1” executive order. While he successfully limited the development of new regulations, evidence suggests that this order did little to actually impose massive repeals of previous regulations. Rescinding a regulation is indeed no easy task—no easier than promulgating a new rule in the first place, given the action must observe the normal process of notice and comment under the Administrative Procedures Act and is subject to the same standard of judicial review. In short, presidents cannot repeal regulations for a blatantly political purpose; they need a reasonable justification. Carefully developing such a justification, complete with supporting evidence, is a time-consuming process that must compete with other agency priorities and is likely to take months or years to complete.

In the meantime, presidents can delay the implementation of a rule until more durable solutions – such as legislation or new evidence supporting different regulations –are found. From Reagan to Trump, all presidents have frozen the pending regulations of previous administrations until they could complete their own review. For those rules that have already been finalized, new presidents can delay their implementation date. Although indefinite rule postponements bring about their own set of legal challenges, temporary delays are powerful strategies for presidents seeking to prevent unsavory policies from taking effect.

In a 2018 article, I examined how factors such as an agency’s ideology, independence, and institutional capacity influenced Trump’s strategy for delaying regulations promulgated in the final year of the Obama administration. Here, I extend that analysis to include Presidents George W. Bush, Obama, and Trump by considering the patterns of regulatory delay in their inaugural year.

The Data on Rule Delay

Drawing from the Federal Register, I compiled a list of final rules promulgated in the closing year of the Bill Clinton (2000-2001), George W. Bush (2008-2009), and Barack Obama (2016-2017) presidencies until January 19th of the new year (their last full day in office). To isolate the rules that are most prone to targeting, I exclusively examine economically significant rules, or those that have “an annual effect on the economy of more than $100 million or more or adversely affect in a material way the economy.”

I then reviewed a list of all final regulations promulgated during the first years of the Bush (2001), Obama (2009), and Trump (2017) presidencies to identify which rules were delayed from the previous administration, the date the rule was delayed, and the corresponding agency. I merged this dataset with information regarding the ideology, cabinet status, and leadership vacancies of each agency. Together, this data produces interesting summary statistics about the patterns of delay across administrations.

Delays Across Administrations

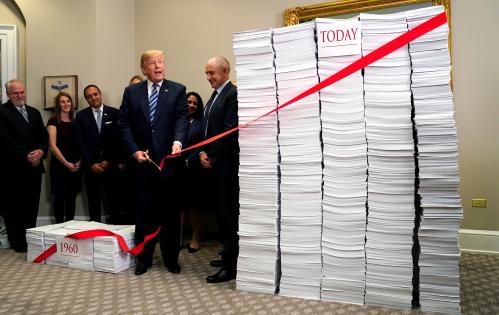

Figure 1 shows the percentage of economically significant final rules each president delayed during his first year in office (depicted in the gray bars). Of the 308 rules promulgated in Clinton’s last year, Bush delayed 44 of them, or about 14 percent upon assuming office. Obama stalled substantially fewer rules, only postponing the implementation of nine out of the 418 rules (two percent) issued by the outgoing Bush administration. At the commencement of his first term, Obama faced an economic recession and a majority in Congress. These factors perhaps shifted his attention away from regulatory repeals towards passing large scare policy changes through legislation. Trump ostensibly falls somewhere in the middle of these presidents. Of the 470 rules finalized by Obama in 2016-2017, Trump delayed 33 of them (seven percent). Since Congress delayed 14 Obama-era rules at the beginning of Trump’s administration under the CRA, there were ultimately just as many regulations postponed during his first year at Bush’s.

Figure 1: Delays Imposed by Sitting Presidential Administration Towards the Rules of Its Predecessor, as a Percentage of Total Rules

Presidents can delay a rule more than once, by issuing subsequent regulations to further stall its implementation date. This tactic was employed across all administrations, as depicted in the dark blue bars in Figure 1. Clearly a favored strategy of Obama, four out of the nine rules postponed (nearly 44 percent) during his first year were pushed back multiple times. This statistic is 28 percent under Bush and 20 under Trump. The largest number of delays a rule received was three, which occurred twice under Obama, thrice under Bush, and four times under Trump on rules written by agencies ranging from the Department of Agriculture (USDA) to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). This commonality across presidencies might suggest an informal, but widely recognized, limit for the number of times a regulation can be delayed before running the risk of judicial intervention.

Presidents are notorious for fast-tracking regulations in their final months of office. These rules are often more unpopular and controversial in nature, as presidents wait to issue them at a time when they can avoid the political fallout. Are these often-hastily finalized midnight regulations more susceptible to delay by incoming presidents?

Figure 1 illustrates the percentage of midnight regulations, or those issued between December 1 and January 19 of the preceding administration,[1] delayed by each incoming president (depicted by the blue bars). In his first year in office, Bush postponed 34 of Clinton’s 88 midnight regulations (26 percent). Of the 114 midnight rules issued by Bush, six were delayed by Obama in 2009 (five percent). Obama later promulgated 130 of his own last-minute regulations, 26 of which were suspended by Trump – nearly 20 percent. Across all these administrations, presidents tend to target midnight regulations at a higher rate than other ones promulgated throughout the preceding year. Though lame duck presidents may rush to finalize controversial rules, they can easily be delayed and ultimately undone by new administrations.

Delays by the Ideology of the Agency

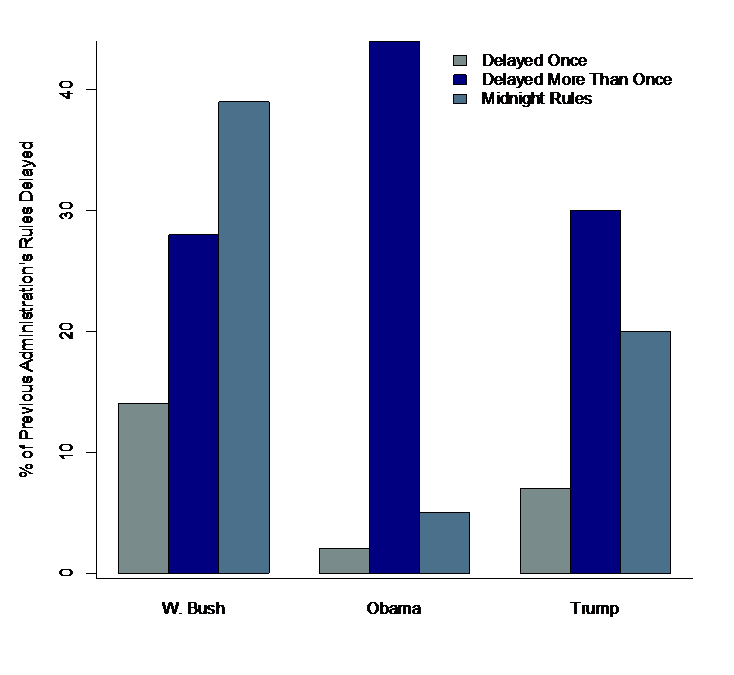

Agencies and their personnel often have liberal or conservative outlooks that influence the ways in which they implement policy. Presidents have incentives to forestall rules that might lead to policies that conflict with their own policy preferences, and are therefore sensitive to agency ideology.

To measure the ideology of agencies, I use the ideal point measures developed by political scientists Adam Bonica, Jowei Chen, and Timothy Johnson (known as the CF scores). These scores are estimated using data on the campaign contributions of agency appointees in federal and state elections, placing them on a liberal to conservative scale based on the ideology of the candidates to whom they donated. Individuals are averaged across agencies and administrations to produce ideal point estimates ranging from -1.5 (liberal) to 1.5 (conservative).

I divide agencies into liberal or conservative camps based on whether they are above (conservative) or below (liberal) the mean CF score under each administration. Figure 2 depicts the percentage of delayed rules promulgated by liberal and conservative agencies. Unsurprisingly, Republican presidents tend to postpone rules promulgated by liberal agencies, while Democrats target rules emerging from conservative ones.

Nearly 61 percent of the final rules that Trump postponed were promulgated by liberal agencies under the Obama administration, such as the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the EPA. Obama went even further, using every single one of his delays on conservative rules issued under Bush, by agencies like the Departments of Homeland Security and Defense. While Obama and Trump clearly targeted rules by agencies with opposing ideologies, Bush used a more balanced approach. In fact, his delays were geared slightly more towards conservative agencies (52 percent) than liberal ones (48 percent).

Figure 2: Delayed Rules by Agency Ideology

Delays by Agency Type

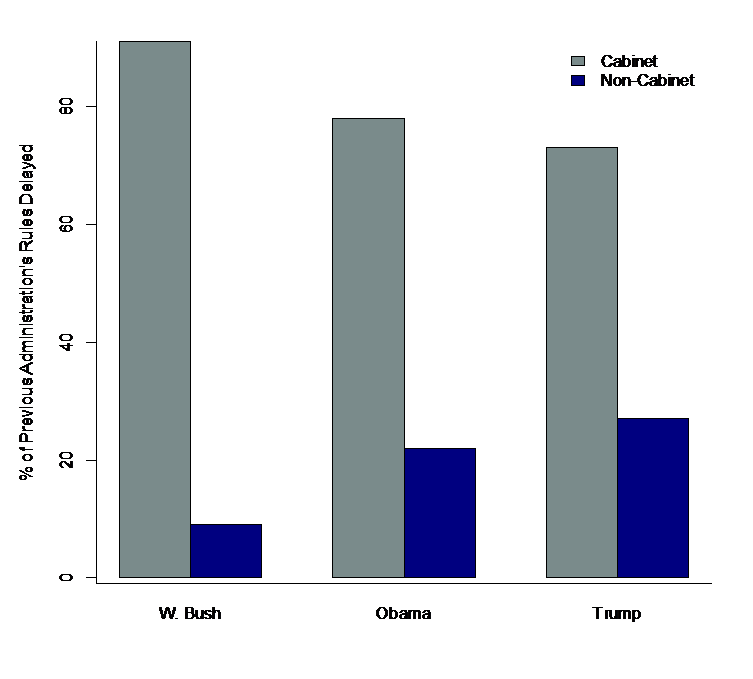

Strategies of regulatory delay are not only influenced by ideology, but also by the degree to which presidents exert control over the agency. Cabinet agencies are more susceptible to presidential control. Presidents can appoint and remove officials from these offices. Their daily activities are funneled through political appointees. Their policymaking outputs – such as budgets, regulations, and legislative proposals – must be cleared through the Executive Office of the President. Independent agencies, on the other hand, are mostly less politicized and less hierarchical. Regulatory commissions are usually headed by an executive, bipartisan board rather than a singular political appointee and their activities are not subjected to White House clearance.

Consequently, Cabinet agencies’ rules should more closely reflect the preferences of their supervising president. These rules should be more prone to the targeting of incoming administrations that oppose their predecessors. I find this exact pattern in Figure 3, which depicts the percentage of delayed rules originating from Cabinet and non-Cabinet agencies. Bush, Obama, and Trump each stalled far more rules from Cabinet agencies – such as the Departments of Interior, Transportation, HHS, USDA, and Defense – than ones coming from independent agencies (e.g. Farm Credit Administration, Social Security Administration, Small Business Administration, and General Service Administration). The greatest disparity occurred during Bush’s inaugural year, with 91 percent of his regulatory delays being imposed upon Cabinet agencies. Obama and Trump, however, were not far behind. About 78 percent and 73 percent of their first-year delays, respectively, were aimed at Cabinet-level rules.

Figure 3: Delayed Rules by Agency Type

Delays under Vacancies

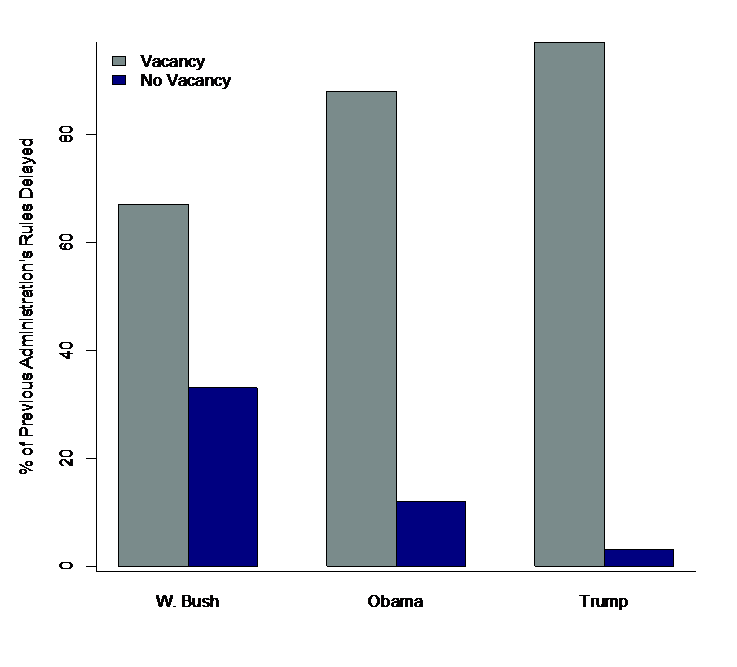

An agency’s institutional capacity – its ability to effectively perform its functions as an institution – can also strongly influence whether and when it decides to delay a forthcoming rule. Resource deficits can leave agencies ill-equipped in the task of rulemaking, forcing them to delay rules in order to afford them more time to figure out how to implement them.

I focus here on one important resource for an agency’s institutional capacity – leadership vacancies. The head of an agency, such as a Cabinet secretary or administrator, provides the leadership, authority, and institutional knowledge to guide agencies in policy implementation. Vacancies in these top positions regularly occur at the beginning of an administration, as political appointees from the previous administration resign and incoming presidents seek new agency leaders. Such vacancies often persist due to lengthy confirmations in the Senate, sudden departures, or forestallments in the nomination process. The absence of permanent leadership can impede agency rulemaking, therefore necessitating delay.

Figure 4 shows the percentage of delayed rules that occurred during periods of vacancies. Most of the delays happened when the top position of the corresponding agency was unfilled. This difference became increasingly stark over time. About 67 percent of regulatory delays imposed by Bush in his first year occurred when the promulgating agency lacked a permanent head. This statistic increased to 88 percent under Obama. Perhaps most notably, an astounding 97 percent of Trump’s first year postponements corresponded to periods of leadership vacancies in the responsible agency. These numbers may be unsurprising given the pervasive vacancies and turnover that plague the Trump administration, even through today. Taken together, a delay does not only transpire for political reasons, but for pragmatic ones as well – when agencies are ill-equipped to fulfill their regulatory responsibilities.

Figure 4: Delayed Rules by Agency Vacancies

Conclusion

New presidents want to influence policymaking as soon as they enter the White House. This often entails erasing the previous administrative policies they find objectionable. Delaying the implementation of last-minute regulations promulgated by their predecessors can afford presidents the time to identify more durable solutions for reversing regulatory policies. Presidents Bush, Obama, and Trump all postponed rules that were finalized by their predecessors, many of which directly conflicted with their own policy objectives. Several of these delays were done for apparently political reasons, on the rules that most conflicted with these presidents’ agendas. They targeted regulations issued by agencies with different ideological outlooks than their own and those that were tightly controlled by the previous president.

Presidents succeeding members of their own party may not have the same motivations for postponing rulemaking activity in this way. For instance, George H.W. Bush’s regulatory agenda likely reflected that of Reagan, thus reducing the need to oust rules for political or ideological reasons. Future studies should examine patterns of delay across all types of transitions.

Administrations, however, do not forestall regulations for solely political reasons. Oftentimes, the institutional limitations that agencies face may necessitate such delay. Resource-poor agencies require more time to figure out how to successfully implement a policy through rulemaking. Beyond leadership vacancies, other resources such as staff quantity, expertise, money, and workload might also influence an agency’s capacity for timely implementation.

What does this mean for the functioning of government? Although politically motivated delay might be difficult to avoid unless major regulatory reforms are implemented, policy lags arising from institutional limitations could be more easily abated by investing more resources into agencies – equipping them with the necessary tools to effectively regulate in a timely manner. Unless such measures are taken, administrative delay will continue to be detrimental for bringing about important policy change.

[1] Similar patterns are found when considering longer periods of midnight activity.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).