Pressure on U.S.-China Relations

A stable and generally constructive relationship between the United States and China has been a central underpinning of peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific region since President Nixon visited Beijing in 1972, and a principal pillar of foreign policy beneficial to vital U.S. interests. But there is no room for complacency about the future of the relationship, or about the stability of the Asia-Pacific region.

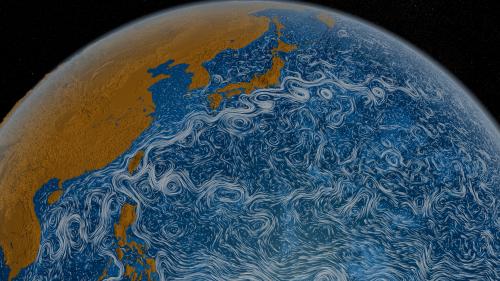

Regardless of the outcome of the U.S. presidential election, there would have been irresistible pressure for sharpening American policy in response to the economic and security consequences of China’s rise. Frustration over Chinese trade and investment practices and inequities in the economic relationship featured prominently in the campaign and are expected to lead to retaliatory measures by the incoming Trump administration. On the security side, frictions between the United States and China in northeast and southeast Asia have mushroomed because of the clash of Chinese territorial and maritime claims with those of rivals, the need for Washington to reassure anxious allies and security partners through its military presence and activities, and the expansion of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) navy’s capabilities and actions.

Whither Asia Policy under Trump?

The world is understandably preoccupied by the foreign policy directions of the incoming Trump administration. There are presently more questions than answers, not least with regard to Asia. Candidate Trump sometimes spoke of allies with disdain, suggesting that they are free-riding moochers who need to pay more for the privilege of American defense and should consider going nuclear. He has promised to renounce the Trans-Pacific Partnership and adopt protectionist trade policies, unsettling to a region that has prospered for a generation based on the open trade and investment policies the United States has sponsored. He has rattled leaders in Beijing by suggesting the United States could abandon its commitment to the “One-China” policy and take other steps to alter its unofficial relationship with Taiwan. Some of his advisors have written of the need to gear up for a trade war with China, whose negative effects would spread throughout the Asia-Pacific region. These are more than the usual rumblings that come with a change of leadership in Washington and are causing widespread uncertainty in the region.

These are more than the usual rumblings that come with a change of leadership in Washington.

On the other hand, there is hope that tax reform and deregulation could boost the American economy, which would benefit the economies of the region. Trump’s foreign policy and national security selections, though few in number so far, generally do not suggest indifference to alliances or support the isolationist messages in his campaign. Amidst Trump’s off-the-cuff remarks and tweets insulting China are occasional comments that he wants a good relationship with China and hints that all is negotiable.

Why China may not want to wait

I have written several articles over the last year with recommendations for U.S. policy toward China. Instead of trying to read the Trump team’s scattered tea leaves and proposing a new way forward, this article will lay out four major initiatives that China, rather than the United States, should take to prevent the all-too-obvious risks of a deteriorating spiral in U.S.-China relations from becoming a reality.

Ordinarily, thinking about major Chinese initiatives to improve the relationship would be a fruitless exercise. But circumstances have changed. The urgency of the situation requires that China’s leaders think and act much more seriously about major shifts in their foreign policy strategy.

Until quite recently, the United States has taken the initiative in the relationship, and China has reacted. This reflected the power disparity between the two countries, U.S. global activism, and the ensuing diplomatic habits. The United States often took the first steps to include or invite China, provided the framework for Chinese inclusion, and coaxed China to participate, as demonstrated by: Nixon’s opening to China; China’s participation in the nuclear nonproliferation regime; the negotiation and terms of China’s membership in the World Trade Organization; the vast array of bilateral trade, military, cultural, educational, and scientific agreements; and regional organizations, like Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and the ASEAN Regional Forum

But times have changed. First, in the last several years, China has established an Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank grouping 57 countries. It has created a regional infrastructure investment plan called “One Belt, One Road” stretching from China through central Asia to Europe. It has hosted meetings of the G-20 and APEC, and put forward organizing themes for each event. It has initiated negotiations for a Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership involving all the major economies of Asia. It has worked to internationalize its currency and persuaded the International Monetary Fund to include the renminbi in its basket of major currencies that the IMF uses to structure balance of payments and debt resettlement loans. It has rapidly become more comfortable with the idea of exercising leadership and initiative, unlike the previous era when it shied away from such activism because of incapacity, habit, or fear of arousing regional anxiety. Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s New Year’s Day interview amply illustrated China’s capacity and self-confidence in moving away from previous year-end laundry lists and in embracing a higher profile approach to global governance.

Second, the 19th Party Congress that will launch Xi Jinping’s second term will be held this fall. It will be the primary focus of Chinese Communist Party politics this year. Xi will want to enunciate policies, achievements, and initiatives that highlight his first term accomplishments and provide a roadmap for the next five years. While Xi will emphasize domestic issues and economic growth, he will not want to ignore the foreign policy steps he has taken or the future directions he wishes to undertake. China’s relationship with the United States arguably will be the most difficult and the most consequential of all foreign policy challenges for China in coming years. As Deng Xiaoping used the Communist Party’s 3rd Plenum in 1978 to launch economic reform and open China to the West, Xi could find a high-profile stabilization of relations with Washington an attractive option to complement his intended domestic policy direction.

Third, Chinese leaders legitimately wonder whether the Trump administration will be responsive to initiatives by Beijing, or if it is instead intent on confronting China and viewing Chinese proposals with suspicion. President Trump certainly will not uncritically adopt Chinese ideas, but he is transactional in his approach to relationships, which involves a readiness to engage in give-and-take. It is thus not in Chinese interest to simply await American initiatives that could frame the subsequent give-and-take discussions on highly disadvantageous terms to China, but instead to offer its own.

Four Proposals for Chinese Action

U.S. attitudes toward China are negatively affected by a host of issues, as are Chinese perceptions of the United States. But there are a limited number of decisive issues that could drive the relationship into one of acute rivalry. If Beijing can acknowledge that it bears some responsibility for how Americans think about China, then a virtuous rather than a vicious cycle could emerge. The ensuing discussion reviews the major issues that are driving suspicions on the American side and suggests ways that China can allay those suspicions while advancing in its own long-term interests.

These recommendations are explicitly designed to move beyond what the Chinese leadership currently considers feasible. None would be easy to achieve, and all would entail substantial risks and costs. They would require sacrifices and concessions by China and reciprocal actions by the United States, though this paper focuses on the actions that China needs to consider. These proposals seek to encourage a paradigm shift in Chinese thinking about managing relations with the United States, rather than rely upon cautious approaches that protect short-term interests but would lead to much larger dangers down the road. I have little expectation that they will be adopted in the short run. But I hope they will spur Chinese leaders and strategists to reflect upon ways to bring the same kind of creative and imaginative approaches to relations with the United States that they have demonstrated in economic institution-building in Asia in recent years.

Economic relations: Time for a new start

There is a widespread view in the United States (given loud voice in the presidential campaign) that the relationship between our two countries is highly unbalanced and damaging the American economy. Among the outcomes that have soured Americans on economic interaction with China are an American trade deficit of nearly $400 billion; shutdown of thousands of U.S. factories unable to compete with Chinese low labor costs; intellectual property violations estimated in the hundreds of billions of dollars; vast disparities in openness to and terms of foreign investment; state subsidies that distort markets and competition; and periodic manipulation of the renminbi to benefit China’s export sector. While there are disagreements among economists over the magnitude of the impact of these practices, there is little disagreement that substantial inequities need to be corrected.

China was admitted to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 through an accord negotiated over 16 years. Its accession was based on an unprecedented agreement to radically open a market and force market discipline upon a state-dominated economy. It was an impressive achievement that benefited both China and its trading partners. In the space of a decade, Chinese imports from the United States grew by 450 percent. (It is true that Chinese exports grew at an even faster rate, but the WTO agreement did not deal with Chinese exports, only with imports and Chinese market opening.)

The accession agreement, and the bilateral U.S.-China trade agreement on which it was largely based, were appropriate for the period when the Chinese economy had yet to fully take off. China was then the world’s sixth largest economy. It was not yet a dominant force in international manufacturing. Its accession agreement was agnostic on the question of whether China was a developed or developing country, essentially treating it as a hybrid. Those facts and assumptions are no longer valid. China is now the world’s second largest economy by a large margin, the world’s largest manufacturing country, the world’s largest exporting and trading country, a significant actor in global markets, and a major source of foreign direct investment. The United States imposes relatively few and targeted restrictions on foreign investment. China, for its part, still sticks to the investment commitments it made during the WTO accession negotiations, which in many key sectors (such as automobiles, telecommunications, information technology, energy, and financial services) cap foreign investment below 50 percent.

Recommendation: China should propose a major renegotiation of both the bilateral investment relationship, including significant liberalization of caps, and of trade practices suitable for China in 2001 but no longer relevant to the economic powerhouse of today. In such a negotiation, China would commit itself to accepting the market discipline and practices accepted by the world’s developed economies. The current negotiations over a bilateral investment treaty could provide a base for some steps, but much more extensive liberalization of China’s investment regime—as well as elimination of barriers to imports—should be envisaged. China should make clear that it is proposing a comprehensive transformation of its trade and investment regime, not piecemeal actions limited to a few sectors.

The greatest political need may be for China to address American trade and investment concerns before the economic relationship becomes toxic.

There are compelling reasons for China to undertake a bolder approach. Its own leaders and top economic thinkers have said over and over that if China does not undertake the next major steps in economic reform, its development will stagnate and it will likely fall into the so-called “middle-income trap.” That is the thesis of the pioneering joint study by the World Bank and China’s Development Research Center published in 2013 and adopted by the Chinese Communist Party at its Third Plenum in 2013. China would also benefit by U.S. and European decisions to accord China market economy status under the WTO if it took the necessary steps promised in such an offer.

Additionally, such a proposal could be effective in warding off the inevitable barrage of trade actions likely to emanate from Washington and other capitals in the coming years. China’s leaders may judge that they have weapons available to retaliate against such actions, but it is far from clear that China has less to lose from a trade war with the United States, Europe, and Japan than they do from a world veering toward protectionism.

The greatest political need may be for China to address American trade and investment concerns before the economic relationship becomes toxic. These proposals would be best in the context of the WTO, which would allow China to respond to the concerns of other major trading partners, including the European Union and Japan. Such a proposal, however, should be tailored to address the urgent concerns of other major exporting countries, rather than reopening a global round of all 164 WTO members certain to take years and unlikely to produce results.

North Korea: The biggest security threat in Asia

North Korea presents a unique national security menace to East Asia and to the United States. It is the world’s most closed society, a brutal dictatorship whose self-perpetuated leadership is accountable only to itself and whose concern for its population seems restricted to keeping them from posing a threat to their rule. It is developing a nuclear weapons arsenal, with a current stockpile estimated at 10 to 20 warheads and growing. It is working hard to lengthen the range of its ballistic missiles so as to enable it to strike the United States with a nuclear weapon. Its ideology and rhetoric are rabidly hostile to the United States and our allies, South Korea, and Japan.

Many observers contend that North Korea’s leaders are not stupid or suicidal, that they know that a nuclear provocation against the United States or its allies would lead to the end of the regime’s existence, that their aims are defensive and limited, and that the kind of deterrence that has worked against other nuclear powers will work against North Korea. That may be so. But it is not an assumption that we can afford to make lightly. North Korea is run by a dictator in his early 30’s with no experience in the outside world, virtually no interactions with foreign officials, no foreign travel in his adult life, no commitment to or stake in relations with the rest of the world, and a record of bloodthirsty if not psychopathic behavior. We should look for a better way to ensure our security and that of our allies than to count on the hope of his growing maturity and restraint.

He sees North Korea as a time bomb on China’s border.

China has a strong interest in seeing a change in North Korea’s behavior and its isolation from the rest of the world. Xi Jinping clearly regards North Korean leader Kim Jong-un with disdain, and has yet to meet with the North Korean leader and China’s former ally. He sees North Korea as a time bomb on China’s border. North Korea’s provocations are undermining China’s national security by inviting ever-increasing American, Japanese, and South Korean military modernization, exercises, and build-up in China’s immediate neighborhood. No less than Henry Kissinger has opined that a major target of North Korea’s nuclear program is China itself. That should give Beijing pause. China has complicated interests in North Korea, but it cannot look upon the current situation with any comfort. Threats of escalation from incidents provoked by North Korea are a deep concern to China, and its preference for a denuclearized North Korea is not mere lip service. China also is uneasy about the possibility of U.S. imposition of sanctions upon Chinese entities that maintain commercial relations with North Korea. The status quo may be an easy day-to-day fallback for China, but it is not in its long-term interest, nor is the increasing security focus of the United States and its allies on its neighbor.

Recommendation: China should decisively move away from its long-term habit of balancing between North Korea and the United States, of valuing short-term but unsustainable stability in the Korean peninsula over addressing seriously the North Korean nuclear threat. To demonstrate its new thinking, it should put forward a comprehensive set of proposals addressing the security concerns of the United States and its allies, consistent with China’s own national security interests.

China should propose that the United States, South Korea, and China begin an ongoing private dialogue about a future nuclear-free unified Korea. The dialogue could begin with sharing of intelligence about North Korea’s weapons of mass destruction programs and proceed to policy and military coordination discussions to deal with possible North Korean collapse scenarios. It also could include questions relating to the U.S.-ROK post-reunification alliance and deployments, which would be of special interest to China and make such discussions more attractive.

Such talks should be accompanied by a more vigorous Chinese economic squeeze on North Korea. China lately has supported tightened sanctions against North Korea and has been enforcing U.N.-imposed measures, but as North Korea’s largest trading partner by far there is more than it can do. It could follow in the footsteps of South Korea, which in the last decade has dramatically curtailed a once modest but real trade and investment relationship with the North.

These pressures need not lead necessarily to the collapse of North Korea that China has long feared. They could instead serve to concentrate the minds of North Korea’s leaders, forcing them to realize that they truly have no path forward beyond absolute international isolation, disappearance of access to luxury goods for the Party elite, and national economic collapse that would imperil the future of the regime. Under such circumstances, North Korea’s leaders might decide to return to the negotiating table, with the offer of inducements such as American diplomatic recognition, a peace treaty, and a relaxation of the international economic embargo. History does not suggest they will make such a decision easily, but there are precedents, though short-lived, in the 1990’s and 2000’s. Or alternatively, if they declined to take the offered path, the regime could collapse. Either would be a more satisfactory outcome for the region and the United States than the current path.

South China Sea: A litmus test on China’s rise

Developments in the South China Sea do not present the same kind of security threat to the United States as does North Korea. But China’s actions in the South China Sea have done more to alter the regional security environment and perceptions of China’s rise than any other actions it has taken in the last decade.

The South China Sea has gone from being a relative backwater in international disputes to a storm center. There are six competing territorial claimants to the region’s thousands of tiny islands, reefs, rocks, and shoals and to associated or nearby maritime areas. The Law of the Sea Convention, whose principles should apply and which were reaffirmed in a ruling last year by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague, has been essentially ignored by China (and unfortunately not ratified by the United States). China has built seven military facilities on reclaimed land on various reefs and rocks, and is developing power projection capabilities and deploying sophisticated anti-aircraft and anti-missile systems. Washington has responded with an increasing rhythm of military exercises and operations, which has led to some dust-ups (e.g. the Chinese snatching of a U.S. underwater drone), warnings, and sharpened rhetoric.

The South China Sea has gone from being a relative backwater in international disputes to a storm center.

The issues in the South China Sea involve an intersecting mixture of territorial claims, great power rivalry, international law, regional interstate frictions, freedom of navigation rights and assertions, and squabbling over marine and energy resources. They will not be resolved comprehensively any time in the foreseeable future. But they can be managed much more constructively, in a way that provides reassurance rather than stokes tensions. All claimants—as well as non-claimant maritime powers like the United States—need to be involved in such a process.

However, China has a special responsibility to do so, because its footprint is so large and growing, its assertions of its maritime claims are inconsistent with international law, and its reputation as a responsible regional stakeholder depends on its demonstrated willingness to accommodate the legitimate needs of other actors. Its coast guard deployments in Indonesian waters, its stationing of oil rigs in waters disputed with Vietnam, and its recent bullying of Singapore demonstrate either clumsiness or a conscious decision that pressure and force are its preferred ways of obtaining results. (The recent China-Philippines reconciliation, whose permanence is far from guaranteed, dropped in China’s lap because of a 180-degree turn by the Philippine’s erratic President Rodrigo Duterte, not because of the strategic brilliance of China’s policy.) If such an approach continues, it can expect the United States, other claimants, and other regional powers to draw harsh conclusions about China’s intentions as its navy expands and to adjust their security and foreign policies in ways to check and constrain China.

Recommendation: If Chinese leaders wish to defuse tensions in the South China Sea, they should put forward a comprehensive proposal building on positions it has taken at various times but failed to pursue seriously. Such a comprehensive proposal could have the following elements:

- An agreement limiting militarization of the South China Sea. This could involve limits on the kinds of weapons systems China and other claimants could deploy on land features. China also doubtless would want to see limitations on U.S. surveillance operations in areas sensitive to China. During his 2015 visit to the United States, Xi Jinping said China did not seek to militarize the Spratly islands. If he were to follow through on that statement, it would go a long way toward defusing tensions.

- A timetable for negotiating a code of conduct among the claimant states. It should cover access to fishing and energy resources. With regard to fishing, China could propose that fleets from all countries could fish freely, within caps designed to prevent overfishing, without regard to geographic or maritime claims.

- China has said it adheres to the Law of the Sea, but its claims and conduct in the South China Sea contradict that claim. It should state unequivocally that the so-called “nine-dash line” is solely for the purpose of delineating China’s claims to islands and other features, not to maritime rights in the South China Sea.

Taiwan

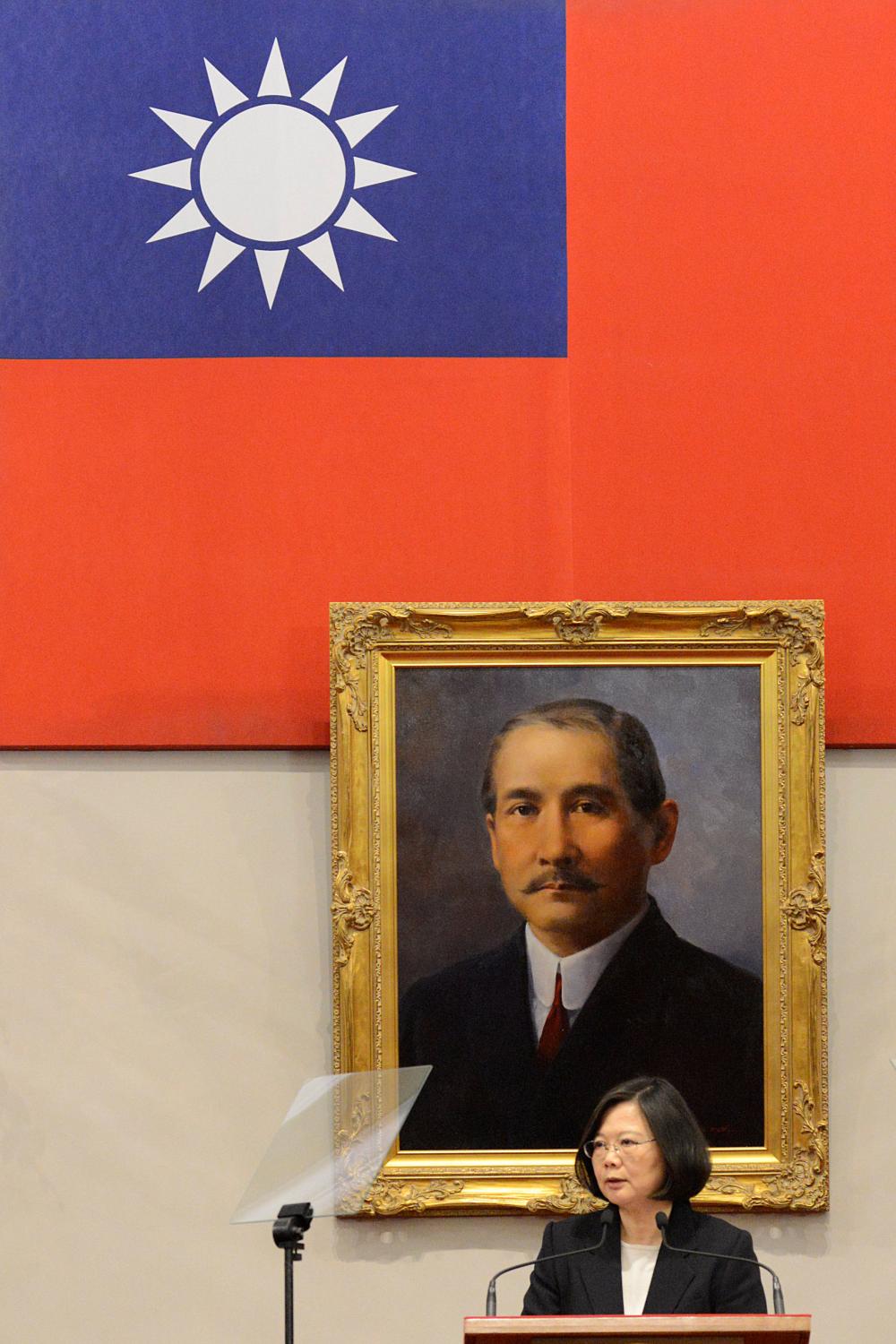

The status of Taiwan is the most sensitive issue for China and its leadership. It is an issue on which the United States has a long-standing position dating back to the three joint U.S.-PRC communiqués—indeed even to the period when the Republic of China was the recognized government of China. U.S. intervention on the issue of Taiwan’s status is welcomed neither on the mainland nor in Taiwan, and President-elect Trump’s offhand comments questioning it would be best forgotten and not repeated. But even without Mr. Trump’s maladroit musings, there is reason to worry about stability in the Taiwan Strait in the next few years. Beijing’s suspicion of the intentions of Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen is just the tip of the iceberg. The larger risk is the divergent directions in popular sentiment on the two sides of the Strait. China’s leaders believe, perhaps correctly, that over time the popular mood is turning against reunification and toward independence. This would be a wholly unacceptable outcome for Beijing. The logic of its “One-China” principle could drive it more toward a policy of pressure and threats against Taiwan, leading ultimately to the use of force if all hope is lost for peaceful reunification. Given U.S. responsibility for Taiwan’s security under U.S. domestic law, that could lead to a test of wills and potential confrontation that would be in no one’s interest.

Viewed against this backdrop, there are clear risks in the next several years. Taiwan’s executive and legislature are now led by the historically pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Tsai Ing-wen, who serves as Party leader as well as president, has refused to accept the One-China principle, which was the basis on which cross-Strait talks were held prior to her election. But she has declared her commitment to the status quo (e.g., no change in Taiwan’s constitution, and no referendum on status). China, in turn, has broken off formal contact with the DPP government, resumed a campaign to isolate Taiwan diplomatically, and could take further steps to pressure Taiwan in the absence of dialogue.

Recommendation: Beijing seems to feel that time may not be on its side, but they cling to an approach to cross-Strait issues that is frozen in time and oblivious to the changes they fear. Consequently, trends are not in their favor, and their approach invites an ultimate Hobson’s choice between acceptance of Taiwan’s permanent separation and the use of force to prevent such separation. It also makes more likely a confrontation between Chinese nationalism and U.S. security responsibilities. Beijing should consider bold ways to change the dynamic, both in their own interests and in the interests of regional peace and stability.

Beijing’s formal position on Taiwan’s future status remains the “one country, two systems” formulation proposed by Deng Xiaoping for Taiwan and Hong Kong in the 1980s. There is no support in Taiwan for “one country, two systems.” China’s continued adherence to it simply serves to isolate it from Taiwan and to entrench hostile views toward the mainland.

The Chinese leadership should consider a reformulation of its Taiwan policy, putting forward an approach consistent with its principles but designed to reach out to Taiwan’s people and change the current negative dynamic.

- Instead of repeating the “one country, two systems” model, Chinese leaders should indicate they are open to a cross-Strait relationship much more in keeping with a Taiwan that has ruled itself for decades. In the 1990s, senior Chinese officials and scholars talked openly about concepts such as confederation, including the relevance of examples like the European Union, expanded international space for Taiwan, or even membership in the United Nations under the concept of One-China. China’s leadership should make clear that concepts for Taiwan’s status more in keeping with existing realities can be discussed.

- Taiwan has been choosing its own leadership through democratic elections since the 1990s. China should understand that it cannot decide who will speak for Taiwan, and a roller-coaster ride in which Beijing turns on and off formal contacts depending on the elected government’s identity is a sure way to sour attitudes in Taiwan. Beijing should look for ways to resume overt contact with Taipei.

- If China were to propose that Taiwan be permitted to join the negotiations on a Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) currently including 16 countries, this would send a powerful signal about Beijing’s attitude toward Taiwan’s economic future and international identity. The same would be true if China were to invite Taiwan to participate in the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank using nomenclature acceptable to Taipei. Neither would require a sacrifice of principle by Beijing.

Bold leaders, and Xi Jinping is one, need to get ahead of the wave, and not wait to be swamped.

Why China Needs a New Strategy

It is almost always easier for a country’s leaders to stay the current course and avoid risk. In Xi Jinping’s case, the course on which he is embarked in foreign policy has involved trade-offs with other senior leaders and assertion of his strength to achieve the present consensus. So change of direction could be painful. China’s foreign policy has created favorable results in some areas, e.g., its building of regional economic institutions that project China’s leadership and a strategic partnership with Russia. But the current trajectory would be filled with perils for China even without an unpredictable American policy under Donald Trump. The apparent collapse of the international consensus on globalization; the rise in protectionism and xenophobia in the West; anxiety and resentment about China’s rise among countries large and small in the West and in Asia; and the likely negative impact of China’s slowing growth rate on its international influence could all play out in ways that degrade China’s international standing. Bold leaders, and Xi Jinping is one, need to get ahead of the wave, and not wait to be swamped.

It would be foolhardy to predict that the ideas in this essay will be adopted by China’s leaders. But they are all in China’s long-term interest, even though that may not be readily apparent to those invested in the status quo. They also would advance China’s relations with the United States, one of China’s most important strategic interests. Chinese and American leaders and experts need to look for opportunities for policy changes that fundamentally change skeptical attitudes on the other side. If they fail to do so, there will be plenty of people on each side with proposals to score at the other’s expense. It is in the spirit of avoiding more worrisome outcomes that I offer these suggestions.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).