Content from the Brookings-Tsinghua Public Policy Center is now archived. Since October 1, 2020, Brookings has maintained a limited partnership with Tsinghua University School of Public Policy and Management that is intended to facilitate jointly organized dialogues, meetings, and/or events.

The Permanent Court of Arbitration unanimously decided to uphold virtually all of the Philippines’ claims against China in the South China Sea this week. That was a victory not only for Manila, but a vindication of the Obama administration’s policy toward the South China Sea since 2010, when then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton publicly and forcefully articulated for the first time the principles underlying American policy.

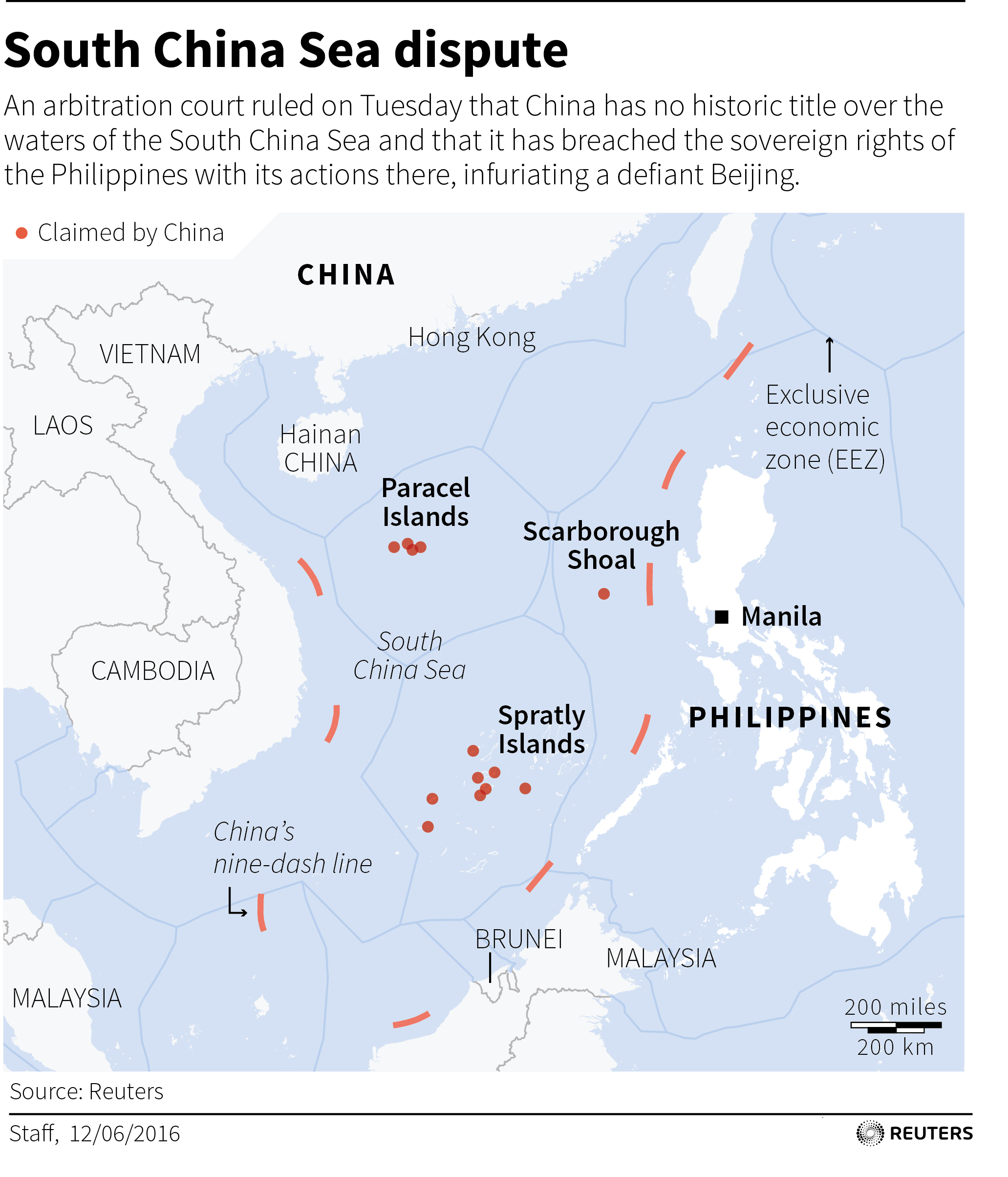

The decision upheld and strengthened all of the principles articulated then and since—the need for maritime claims to be based on legitimate land-based claims, the need to conform maritime claims to the rules of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the conflict between maritime claims based on China’s nine-dash line, and international law. A ruling of particular importance to the United States was the decision that no features in the South China Sea’s Spratly Islands can validate a 200-mile exclusive economic zone (where the littoral state enjoys fishing and mineral exploitation rights). This prevents any legal basis for carving up the South China Sea into walled-off spaces, which would have been utterly impractical and laid the basis for endless conflict, but also undercuts any future attempt to restrict the freedom of navigation for American naval vessels.

But of course the decision will not implement itself, and China, unwisely and unfortunately, has already made clear it has no intention to accept it. China’s growing naval power in the area cannot be offset by the other claimants, individually or collectively. Only the United States can restrain it from excesses, and continuous confrontations between the United States and China in an area important but not central to U.S. national security would be an undesirable path forward.

The mood in China in the wake of this decision will be one of humiliation and anger. These are not sentiments that generally lead to sound decisions. So how can the United States best proceed in a way that upholds the principles the tribunal affirmed but allows Beijing to get out of the corner it has painted itself into? The United States should do some things, and China will have to do some things, more things.

Philippine Foreign Secretary Perfecto Yasay gives a brief statement regarding the tribunal ruling on the South China Sea during a news conference at the Department of Foreign Affairs headquarters in Pasay city, metro Manila, Philippines. Photo credit: Reuters/Romeo Ranoco.

Washington’s move

While properly welcoming the decision, Washington has been restrained in self-congratulatory rhetoric. The Philippines has as well, even though it is the victor in this litigation. That is an important posture and a first step in incentivizing the Chinese to look for a constructive way forward.

Washington should make clear to Beijing that it strongly supports dialogue between China and the Philippines to reach a modus vivendi, the elements of which are not hard to envisage: shared fishing rights in and around Scarborough Shoal, removal of the Philippine marine platoon from the rusting hull of a ship beached on Second Thomas Shoal (ruled by the tribunal to lie within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone), and Chinese economic assistance and infrastructure support to the Philippines. Beijing wrongly believes that Washington encouraged Manila to bring the case to the tribunal in the first place. U.S. support for a China-Philippines deal would undercut Beijing’s belief that the United States is the source of all their problems in the South China Sea.

U.S. support for a China-Philippines deal would undercut Beijing’s belief that the United States is the source of all their problems in the South China Sea.

The U.S. Navy has undertaken a high rhythm of freedom of navigation exercises, some just off the coast of China-occupied features in the Spratly islands. These were necessary to prevent the international community’s rights from being extinguished by failure to exercise them. With the tribunal having made clear that no Spratly feature enjoys more than a 12-mile territorial sea, the need for so many or such visible exercises in the face of the Chinese has diminished. The United States should avoid exercises right up against Chinese installations that will be seen in Beijing as gratuitously provocative, since our rights are now clearly recognized by the principal international body responsible for adjudicating such issues. At the same time, Washington needs to make clear that the tribunal’s decision does not mark the end of U.S. interest or military presence in the South China Sea, which needs to be continuous.

Some have suggested that other claimants, with U.S. encouragement, should bring their own cases to the tribunal. This would not be in the United States’ interest, however. The tribunal has already decided most of the issues of concern to the other claimants to be in their favor, by implication. The additional benefit of an explicit tribunal blessing would not be worth the likely escalation in tensions that would be brought by such a strategy.

The Tribunal was bold in laying out its conception of the high bar that a feature, in the South China Sea or anywhere in the world, must clear in order to be deemed an “island” rather than a “rock” meriting a 200-mile exclusive economic zone. The United States has several features in the Pacific that meet the tribunal’s definition of a “rock” that we currently consider “islands.” It would give the United States the moral high ground and set an example for South China Sea claimants if we announced that we were reconsidering the status of those features.

Finally, the U.S. administration—and the Clinton campaign—should make clear that they are prepared to expend political capital to seek Senate ratification of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea. We have based our policy in the South China Sea on UNCLOS’ validity. Countries are right to point to our hypocrisy in insisting on their acceptance of the convention’s strictures while we stand apart from it. Every former secretary of state, the Navy, former secretaries of defense, and the business community all support accession to UNCLOS as overwhelmingly in the United States’ interest. We should make this a national priority. We cannot expect China and others to pay attention to UNCLOS if we continue to say: “do as we say, not as we do.”

Countries are right to point to our hypocrisy in insisting on their acceptance of the convention’s strictures while we stand apart from it.

Beijing’s move

China needs to make clear that it will not undertake military or paramilitary actions against the Philippines or the territories or facilities of other claimants. In recent months it seems to have reconsidered its apparent plan to fortify Scarborough Shoal. If it reverses that, it will rekindle the sense of crisis in the region and in Washington. The Chinese also should not impose either formal or informal economic sanctions against the Philippines, which will heighten nationalism and undercut attempts to start a dialogue.

China also should refrain from further land reclamation projects on features that have been ruled to be “low tide elevations” that one cannot claim in another country’s exclusive economic zone. Of course it would be best for China and other countries to refrain from all land reclamation projects in the Spratlys, but such a complete moratorium may be unrealistic to expect.

The nine-dash line has been an albatross around China’s neck, a symbol of its vague but excessive maritime claims that no one outside China can defend. The tribunal has made clear that China cannot claim historical rights to fish in the Spratlys on the basis of the nine-dash line. If China cannot get itself soon to clarify the nine-dash line consistent with UNCLOS, at a minimum it should stop talking about it in a way that suggests it conveys any maritime rights. Similarly, the tribunal explicitly rejected China’s recent suggestion that it could claim maritime rights within the Spratlys based on the notion that the Spratlys is a “unit” rather than a series of unconnected rocks. China should drop that assertion, and abandon any intentions either to draw “straight baselines” contrary to UNCLOS around the Spratlys or to establish an air defense identification zone in the Spratlys.

China should accelerate hitherto lackluster efforts to negotiate a “code of conduct” for actions in the South China Sea with the other claimants. The code should embody key principles outlined by the tribunal, allowing China the opportunity to demonstrate its adherence to international law without requiring its overt acceptance of the ruling to which it objects. It also should lay the basis for establishing a fishing regime in the South China Sea that allows the fleets of all claimants, and others, to fish without regard to maritime boundaries that the tribunal has ruled illegal. Under such a construct, parties would only be constrained by a multilateral commission whose role would be to prevent overfishing.

Moving forward together

Finally, the United States and China should follow up on President Xi Jinping’s statement during his visit to Washington last year that China does not intend to militarize the Spratlys by conducting a serious dialogue on what “militarization” means. The two governments should talk about what kinds of force projection and weapons have dangerous escalatory potential, and agree to refrain from or restrain their deployment. This obviously will be a difficult conversation, since the U.S. concern is with what weapons systems are deployed on land features in the Spratlys, while China’s concern is with U.S. naval deployments in the Spratlys that we consider part and parcel of our normal operations. It may be that clear and binding agreements will prove impossible, but a dialogue could produce agreement on the need for restraint that would provide reassurance for all the parties in the region.

U.S. policy to date has been a mixture of military signaling, diplomatic rallying of like-minded states, reliance on international law, public articulation of principles, and dialogue and warnings to the Chinese. All of these have been important, and none can be abandoned. But the tribunal’s decision provides a chance for all the parties to step back and rethink their strategies based on the new reality created by its far-reaching ruling.

It offers us an opportunity to move toward a resolution of key issues based on more serious inter-state consultations founded on international law. But it also creates the risk of higher tension if the Chinese reaction is driven by hyper-nationalism. A mid-course adjustment is necessary, building on the real achievements to date highlighted by this decision but mindful that legal decisions will not by themselves compel all the actors to behave wisely and peacefully.

Commentary

What the United States and China should do in the wake of the South China Sea ruling

July 13, 2016