China’s estrangement from North Korea continues to fester and deepen. Following protracted negotiations in the aftermath of Pyongyang’s fourth nuclear test and subsequent satellite launch, the U.N. Security Council has imposed far more severe restrictions on North Korean trade, finance, and maritime activities. The resolution—which passed on March 2 and for which China was a key drafter—portends a much edgier and uncertain relationship between Beijing and Pyongyang.

Though there are ambiguities and loopholes in the criteria and enforcement provisions governing the resolution (UNSCR 2270), the new sanctions have much sharper teeth than previous resolutions—and China has unequivocally pledged to uphold the letter and spirit of the council’s decision. Even before the resolution passed, South Korean and Chinese media reported that financial transactions in the city of Dandong (where most border trade takes place between China and North Korea) had been sharply curtailed.

By mid-March, Beijing was notifying local authorities on the procedures for implementing the sanctions, which will inhibit North Korean exports of coal, iron, and other minerals—the largest source of Pyongyang’s foreign exchange earnings with the outside world. At the same time, Chinese authorities were sharply limiting access of North Korean ships to ports across northeastern China, and according to some reports have barred the entry of North Korean freighters into specific ports.

Turning up the dial

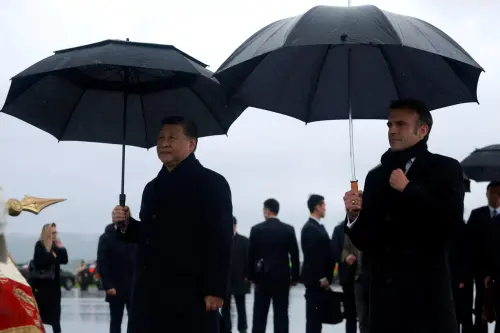

So, after China’s radio silence following the fourth nuclear test, Beijing has now decided to make Pyongyang feel the pain. The Chinese also plan to consult more closely with the United States and South Korea, with President Xi Jinping planning to meet President Obama on the sidelines of this week’s Nuclear Security Summit in Washington. President Xi will likely meet separately with South Korean President Park Geun-hye, as well.

For the first time, China has begun to fully acknowledge that North Korean actions pose a direct threat to vital Chinese security interests.

For the first time, China has begun to fully acknowledge that North Korean actions pose a direct threat to vital Chinese security interests, and that Beijing is no longer prepared to rationalize or ignore the threat. Beijing has also concluded that its inaction was damaging personal and political relations between President Xi and President Park. But the driving factor is that China is no longer prepared to tolerate the cavalier, near-contemptuous attitude of Kim Jong-un, North Korea’s impetuous young leader, toward his principal source of economic support.

China insists that it desires normal, nominally co-equal relations with both Koreas. But Beijing’s ties with Seoul and Pyongyang are already highly imbalanced. China and South Korea have extensive economic and political relations; China and North Korea, in contrast, are increasingly alienated—which (despite shared revolutionary origins and China’s major sacrifices in the Korean War) represents an increasing liability to Chinese interests.

China is thus at long last prepared to connect the dots in its relations with North Korea. It also objects strenuously to discussions between the United States and South Korea on the prospective deployment of terminal high altitude area defense (THAAD) missiles and advanced radars on the peninsula, claiming that they undermine the credibility of China’s strategic nuclear forces. But Washington and Seoul speak with one voice: If THAAD and its associated radars are deployed, they will focus exclusively on current and projected North Korean missile threats, and are not designed to weaken China’s nuclear deterrent.

[T]he driving factor is that China is no longer prepared to tolerate the cavalier, near-contemptuous attitude of Kim Jong-un.

Patience wearing thin

China voices understandable worries about the prospect of an acute crisis on the Korean peninsula, but it increasingly places the blame on its isolated, nuclear-armed neighbor. As observed in an editorial in the popular Chinese paper Global Times:

“North Korea must not overestimate its ability to control danger…The United States has the strength to drastically change the rules of the game…Pyongyang should not expect China to be able to protect its security through UNSC channels when it engages in reckless risk taking…what it creates will be a situation that China simply cannot control. Nuclear weapons and missiles are indeed powerful strategic tools, but in North Korea they have brought real and imminent national strategic risks.”

Such sentiments have never before been voiced openly at such authoritative levels in Beijing, but they have now entered mainstream Chinese strategic debates. In an extraordinarily frank interview during a recent visit to South Korea, Ambassador Wu Dawei, China’s long-time lead negotiator on the Korean nuclear issue, expressed mounting frustration that North Korea lets China’s advice “go through one ear and out the other ear.” Ambassador Wu ominously asserted that by refusing to forego its nuclear and missile capabilities, North Korea had “signed its own death warrant.”

Has China concluded that North Korea is on borrowed time? As observed in another Global Times editorial after passage of the new sanctions resolution, Beijing has made clear that it is not prepared to rescue Pyongyang from a “lethal misjudgment” where “the United States and South Korea hold lots of better cards.” It added that UNSCR 2270 “eradicates North Korea’s illusion that it can divide the great powers. The resolution sends a clear signal: there is no future for North Korea’s possession of nuclear weapons.”

As China and the other members of the Security Council acknowledge, the sanctions won’t take full effect for a while. But is Pyongyang listening? What happens if it persists in its willful defiance of the international community and develops ways to undermine or circumvent the desired effects of the sanctions? How does China then prepare for the worst with its endlessly troublesome neighbor, and can it work with others to forestall the most severe of potential crises? There are no certain answers to these questions, but China has at last begun to pose them.

Commentary

China and North Korea: The long goodbye?

March 28, 2016