Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

In this India-U.S. Policy Memo, Tanvi Madan writes that getting that substance right is a necessary and crucial condition for taking the India-U.S. relationship to the next level. She emphasizes that getting the style right is critical too and suggests ways to improve this aspect of the relationship.

If you hear the loudest voices, you’d think the India-U.S. relationship was full of crises—not one that has arguably come further and faster than any other relationship for either country. And yet, since the two countries are democracies, these voices cannot be ignored because they affect the narrative and tone of the relationship that, in turn, can shape its substance. Thus, much as getting that substance right is a necessary and crucial condition for taking the India-U.S. relationship to the next level, it is not a sufficient one.

There have been substantive reasons for sentiment and signal suffering over the last few years, including differences, and drift because of other priorities. Yet, there have also been some reasons related to style: First, the political leaderships don’t sufficiently explain the value of the relationship. Second, some advocates of the relationship inadvertently set unrealistic expectations that, when unmet, lead to disappointment. Third, while historical baggage, stereotypes and assumptions abound, there is not enough knowledge about the other country—including the constraints, complexities, constituencies, and the actors and processes involved. For example, there are few real experts focusing on the U.S. in India. Fourth, each country has a vibrant free press, which often focuses on the relationship only in tense times. Fifth, the constituencies that benefit from the relationship rarely speak up either because of lack of incentive or because of the behind-the-scenes nature of some initiatives.

So how can one get a clearer signal, with less noise? What’s needed is not just a whole-of-government approach, but a whole-of-country one, involving federal and state governments, politicians, business, think tanks, the media, and the public. Some recommendations:

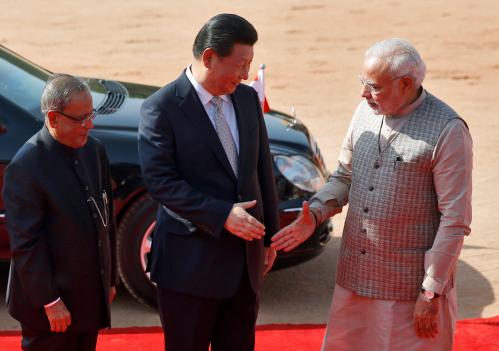

Explain. The India-U.S. relationship will be more sustainable and smoother if each government explains to its own bureaucracy and public, as well as the other’s, where the other country fits into its strategy. There has been a reluctance to talk about the utility of the relationship, lest this be seen as “transactional,” but it needs to be elaborated. The two governments have taken some steps to engage the media and opinion makers—this should continue. In the near term, other specific steps could include, for example, a public message from Prime Minister Modi timed with his visit, explaining his government’s perspective on, as well as its ambitions and plan of action for the relationship with the U.S.

Learn. Government and business in each country can encourage learning about the other country. High net-worth individuals can create a significant scholarship fund for Americans and Indians designed to increase understanding of contemporary India and the United States. In addition, government and business can facilitate study tours for influential Americans and Indians. There can be study tours or short-term fellowships in the other country specifically for journalists, who are not just observers, but actors in the relationship. There can also be fellowships for bureaucrats to learn about the political system in the other country. The Indian government, in particular, can also do more to ease the ability of a greater number of Americans to work and study in India. Those who cover bilateral relations can also learn about more the other country and the relationship—today technology has made it much easier to do so, not least by making primary sources of information more accessible.

Deal with differences. Differences are unavoidable, but American and Indian officials can continue to work together to minimize the negative impact of differences, for example, through advance consultation and notification. To the extent possible, the governments and private sectors should also deal with differences privately—when they play out publicly, they tend to elicit a counterproductive reaction. Furthermore, both sides should have a plan for cooling tempers when differences become public, including by making it easier for the other side to deal with domestic constituencies. Finally, constituencies that benefit, including businesses and states, should highlight these benefits because the tone of the relationship will shape their operating environment. For example, business groups like the Confederation of Indian Industry, the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry, and the U.S.-India Business Council can issue a joint statement highlighting areas of shared interest and agreement.

Manage expectations. There are reasons for supporters of the relationship to “sell” its benefits: It helps attract attention, resources, and more supporters. However, a balance needs to be struck between underselling the relationship to the point it is ignored and overselling it to the point that unrealistic expectations are unintentionally set. Expectations don’t have to be moderated, but need to be managed. Setting a multi-year plan for the relationship would help, with realistic implementation timelines laid out. Visits and dialogues might need to be restructured to focus on particular initiatives, perhaps modeled on the joint-task-force-style State-Commerce-Defense meeting that Defense Secretary Hagel proposed to his Indian counterpart. But big deals—of the civil nuclear deal kind—should not be expected from every high-level visit and should not be the sole measure of the state of relationship. Finally, expectations from such visits can be managed somewhat if such contact is regularized. Summits between American and India leaders, for example, should not be a once-in-an-administration deal, but annual or biennial. President Obama can take a step in this direction by becoming the first American president to visit India twice while in office.