In March 2021, Congress passed the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA).1 ARPA delivered resources to mount a public health response to COVID-19; directed economic relief to workers, families, and small businesses; and provided fiscal aid to state, local, and tribal governments through the $350 billion Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) program.2 For local governments, which received $130 billion, the SLFRF program provided an unprecedented amount of funding alongside considerable flexibility to address both the acute effects of the COVID-19 crisis and the long-standing local challenges that exacerbated the impacts of the crisis on economically disadvantaged communities. The Department of the Treasury set deadlines for SLFRF dollars to be obligated by December 31, 2024 and spent by December 31, 2026.

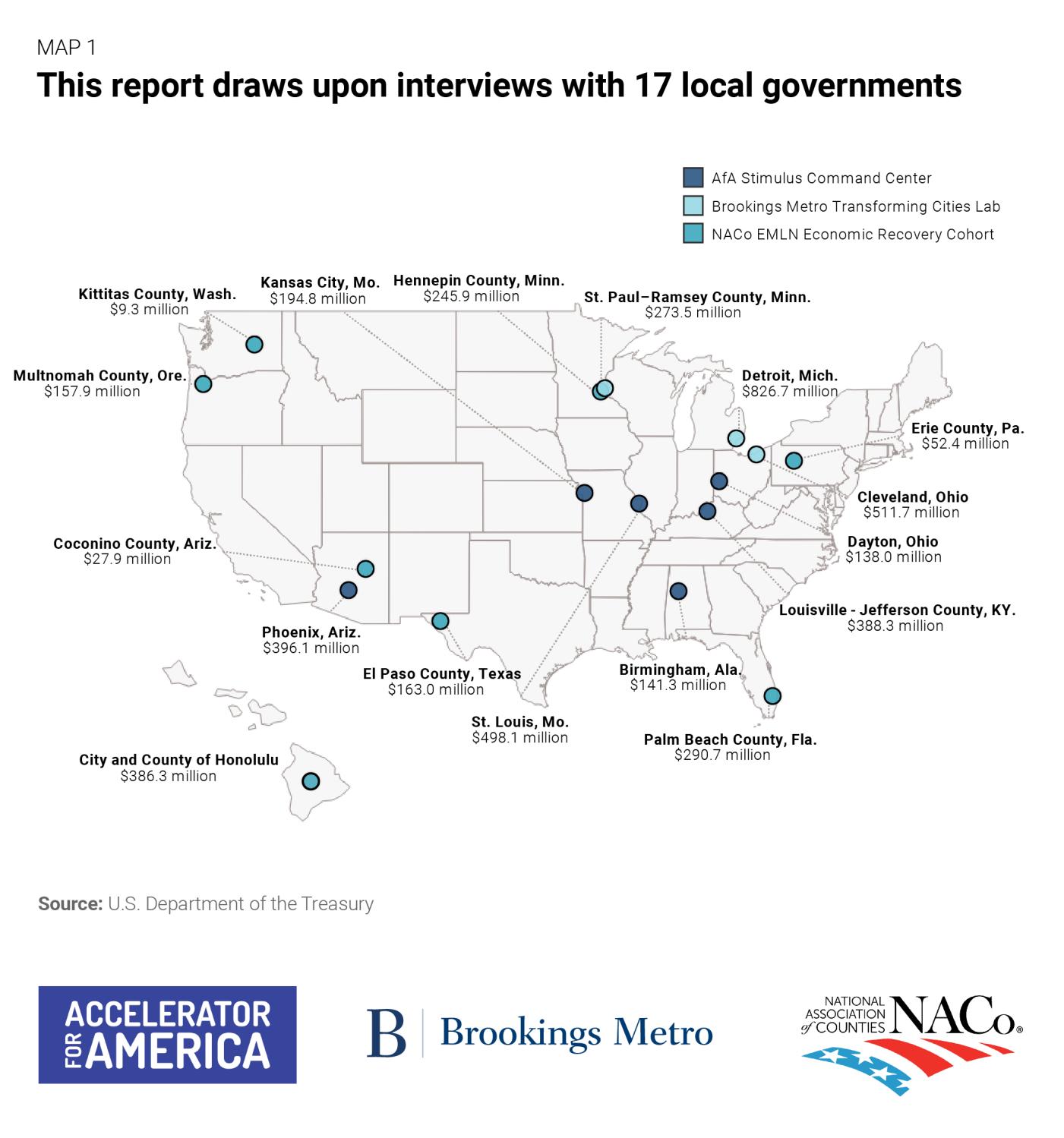

To mark ARPA’s two-year anniversary, this report examines how local governments utilized the SLFRF program to spur an equitable economic recovery. Over the past two years, our organizations—Brookings Metro, Accelerator For America (AFA), and the National Association of Counties (NACo)—have been tracking ARPA implementation and working with local leaders in cities and counties across the nation on how to best deploy their SLFRF allocations. These on-the-ground engagements yielded considerable insights on how local governments navigated the complexities of ARPA implementation. Building on those applied projects, in early 2023, we conducted in-depth interviews with local decisionmakers in 17 cities and counties to explore how they engaged community stakeholders, established recovery priorities, developed strategic investments, and monitored and evaluated ARPA’s early impacts.

Three major findings emerged from this research, each corresponding to a key phase of ARPA planning and implementation within local governments:

- Local government leaders set priorities for local recovery, which were influenced by regulatory and political uncertainty, strategic continuity, and community engagement. In spring 2021, city and county officials were still very much in crisis mode, yet most all recognized the strategic importance of the SLFRF allocations they were about to receive. Confronted with this balance of crisis management and longer-term strategic planning, localities have been impressively entrepreneurial and innovative in setting priorities for SLFRF dollars in ways that drive greater inclusion and equity in their communities. Local leaders arrived at these priorities amid considerable uncertainty in the SLFRF rulemaking process and broader political debates in their communities. Some local governments established strategic priorities for ARPA investments based on pre-existing strategic plans, while others used the crisis to forge new or refreshed visions. Finally, community engagement in priority-setting was possible but not universal, and its degree differed from place to place.

- Local governments pursued “dual-track” investment strategies, using the SLFRF program to both implement emergency relief and government stabilization measures as well as invest in rebuilding a more equitable economy. When the federal government allocated the first tranche of SLFRF dollars in spring 2021, local health and fiscal conditions necessitated that many local governments use the resources to invest in three key pillars—government operations, public health, and community aid—that would stabilize communities and local government. This first track (investments to rescue the economy) was followed by a second track focused on rebuilding the economy on a stronger, more inclusive foundation via investments in workforce, small businesses, housing, infrastructure, and neighborhood revitalization. Ultimately, well-designed approaches shared three characteristics. First, they were inclusive in their design—targeting historically disadvantaged households and neighborhoods. Second, they were sustainable—primarily one-time capital investments that will deliver sustained returns over time. And third, they focused on systems-level design that leveraged additional funders and improved capacity across entire policy domain systems (e.g., workforce, small business, community development).

- Local governments are responsible for measuring impact across a range of projects, which is forcing them to upgrade their evaluation and tracking capabilities. One concern in implementing the SLFRF program was whether local governments could expand their performance management systems to track obligated and expended funds, assess outcomes, and report both pieces of information in a timely fashion to the Treasury Department. A relatively small set of local governments are investing in capacity to make the data that they report to Treasury accessible to the public at large. These online trackers and dashboards are allowing researchers, the media, and citizens to better understand the program’s early outcomes across individual projects and broader strategic domains. Given the SLFRF program’s expected impact on broad local outcomes (rather than just the outcomes reported to Treasury), some local governments are also using a more comprehensive set of indicators to track the recovery and provide critical context for their investments.

Finally, with the ARPA expenditure deadline looming, local leaders are focused on the long-term implications of SLFRF investments for their communities. This multidimensional challenge requires local leaders to sustain ARPA funding impact through a mix of strategic initiatives, existing and new complementary funding, greater cross-jurisdictional collaboration, and new impact-performance metrics. Federal agencies are key partners to local governments in ARPA funding, so enhancing flexible funding and organizing across those agencies could make a difference in ongoing implementation.

-

Footnotes

- U.S. Department of the Treasury (n.d.). “About the American Rescue Plan”. Retrieved from https://home.treasury.gov.

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. (n.d.). “State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds”. Retrieved from https://home.treasury.gov.

Commentary

From recovery to revitalization: How local leaders are unlocking the potential of the American Rescue Plan

June 12, 2023